Today, apropos of nothing in particular, I would like to share the story of an immigrant.

In 1994, Nikolay Synkov, a Russian naval engineer, came to the United States with his wife Tatiyana and their three children. Like countless others, he came to America seeking opportunity and prosperity. He found both by starting a small business—a home repair company that would indulge his unfulfilled passion for architecture.

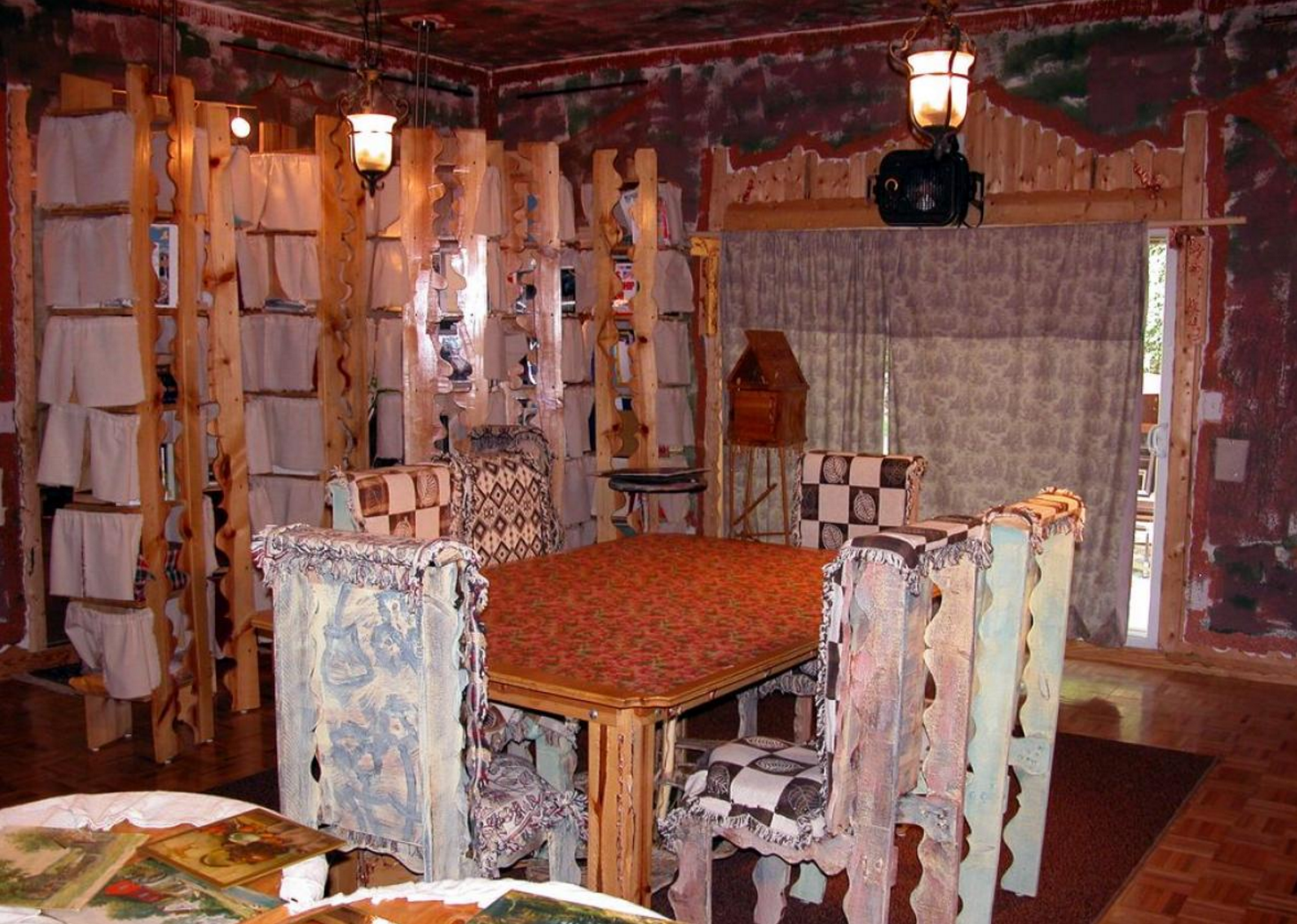

It would also lead to the purchase of that timeless emblem of American middle-class success: a large, beautiful suburban home. In 2001, the Synkovs bought an 11-room house at 24 Brentwood Drive in the tony town of Avon, Connecticut. They promptly set about gutting it. For four years, Synkov would work 40-hour weeks leading a team of at least seven, including his children, in the fulfilment of a remarkable vision. This was no mere remodeling project. Synkov, who now describes himself as a self-trained artist working within the medium of the “single-family home”, wanted the house to give voice to an idea. That idea, as explained in a 2008 profile in Connecticut’s Hartford magazine, was “that peace is more honorable than the tragedy of war.” By the end of Synkov’s work, the house would be nearly double its original size and accompanied by well over 100 pages of accompanying documentation and poetry inspired by the paintings and writings of Wassily Kandinsky, the ideas of German philosopher Martin Heidegger, and Slavic migration, among other things.

The house has been listed on Zillow—where it is described as featuring “unique one of a kind finishing completed by a professional”—on and off since 2013. Synkov, it seems, is ready to move on. It is thanks to that listing, updated just last month, that the whole world can finally see what he has been up to.

Screenshot/Zillow

The Zillow page, which has 51 photos in total of the house and amounts to the first major exhibition of Synkov’s work, has slowly been making its way around Reddit since its posting to r/diWHY, a subreddit dedicated to do-it-yourself mishaps. A few typical examples of the public response: “Jesus Christ, that house is like a bad time on acid.” “Its like someone wanted to live in side of a house made of meat.” “I imagine this is what hell looks like. The chocolate staircase looks evil.” “That house is hands down the ugliest thing I have ever seen that was made on purpose.”

Screenshot/Zillow

The names of great artists unappreciated in their time could fill volumes—volumes that Synkov would perhaps use to wallpaper his master bedroom. What many such artists lacked was a public capable of understanding them and their works in context. With Synkov’s work, the incurious eye might be put off, for instance, by the juxtaposition of floral patterning and what appear to be human entrails affixed to the walls of the home’s main living room. But this mild clash makes infinitely more sense when one learns the room is intended to represent the trials of Don Quixote. The staircase may indeed look like it had a viscous and fast-hardening mixture of dark chocolate and blood spilled down it recently, but its appearance is explicated, in verse, by an accompanying 41-line poem called “Main Sheet of Remembrance: There Was No Storm. It Turned into a Wind Blowing Some Bubbles,” helpfully translated into English by Nikolay’s daughter Yelena. “What should I remember/ What to remember,” it begins. “Somersaulting everything flying at once/ How to forget, what to retell/ Or should everything going its course.”

Screenshot/Zillow

And what about Synkovs themselves? Would critics dismiss them so readily if they knew Nikolay and his wife drive a car with an inflatable Minion pirate and dragon attached to its roof as a trenchant critique of Russian president Vladimir Putin? Or that the house had also been home to an entirely different Synkov family project called the “SCHWIPAR Centre for Innovational Development Against the Balance of Interests,” which, on a page topped by a photo of a warship, says it offers expertise and consulting for those in the shipbuilding, aerospace and heating, cooling, and refrigeration industries?

Sadly, none of the above has made enough of an impression on potential buyers to yield a sale. The house is currently listed at $339,000, down from a peak asking price of nearly $1.5 million. If the price drop and Muzak-soundtracked virtual tours don’t work, it’s conceivable that Nikolay’s art will have to be destroyed to make the house “livable” by the usual standards of Avon, Connecticut.

Screenshot/Zillow

Nikolay is the founder of the Fermata Arts Foundation, an organization dedicated, it says in its mission statement, to aiding, through art, “in the preservation of peace through mutual respect, understanding and cooperation.” The Fermata Arts Foundation has backed colorful youth art exhibitions here in the U.S., the U.K., Latvia, Georgia, Kazakhstan, Tajikistan, and, this past August, in Ukraine. The latter event even earned the writing of a welcome letter to participants from Connecticut Sen. Chris Murphy, who praised Fermata for making “meaningful progress in connecting the subjective experiences of Americans and individuals from post-Soviet states.”

The organization’s web presence is scattered and sketchy, but it can be gleaned that Fermata also hopes to back more artistic projects like the house at 24 Brentwood in the U.S. In fact, its webpage alludes to the existence of two more Synkov houses in Portland, Oregon, and Newton, Massachusetts, which are featured on a page at the site of Synkov’s home repair service. “One of the most important goals of these projects,” Fermata’s site says, “is the expression of the subjective reality of freedom in the United States, and how this becomes a multifaceted gift that actualizes itself in numerous ways for immigrants to the United States.”

Twenty-two years ago, one such immigrant arrived speaking two languages most here wouldn’t understand—one literal, one visual. He came to create, and he did, like so many enterprising immigrants before him, with the help of a loving family. Take a good long look at this home. You are staring at a vision of the American dream—wild, dissonant, radically different, radically free, and shaped wholly by its makers. Surrounded as we are by immense ugliness—figures that would have us tilt at windmills seeking enemies among those who come here with hope in their hearts—24 Brentwood can only be seen as beautiful.

Read more in Slate: