Shannon Plumb, wife of Light Between Oceans director Derek Cianfrance, recently published a scathing essay in which she blames the drama’s disappointing opening weekend at the box office on early reviews—specifically, those by male critics. The film, which stars Michael Fassbender, Alicia Vikander, and Rachel Weisz, brought in just under $5 million in its first few days, something Plumb attributes to reviewers such as Variety’s Owen Gleiberman using terms like “weepie,” “chick flick,” and “melodrama” in association with the film. “Great,” laments Plumb. “Now the fireman, the garbage man, and my Uncle Rocky won’t go see it.”

The disdain of these men, according to Plumb, is a symptom of a greater societal ill, the death of romance in an age of cellphones and emoticons. But The Light Between Oceans has bigger problems than belonging to a genre that, Plumb seems to say, appeals disproportionately to women. (If romance were truly dead, Damien Chazelle’s La La Land wouldn’t be the darling of just about every film festival in the world right now.) The truth is, Cianfrance’s film is a weepie. And it didn’t need to be.

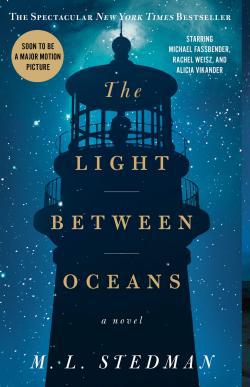

The Light Between Oceans is based on M.L. Stedman’s 2012 novel of the same name, which has spent years on the New York Times best-seller list. Cianfrance’s adaptation, which he wrote and directed, remains loosely true to Stedman’s plot: Lighthouse keeper Tom (Fassbender) and his wife Isabel (Vikander) are unhappily childless, until one day, in a twist straight out of a fairy tale, a baby washes up on the shores of their little island. Against Tom’s better judgement, they secretly adopt the baby as their own daughter, only to find out, years later, that the girl’s mother, Hannah (Weisz), is still alive, miserable, and—surprise!—living in the nearest harbor.

Scribner

Here the two versions diverge: In the novel, both Tom and Isabel find out that a local woman lost her husband and baby at sea, and though they connect the dots, Isabel insists that the damage is done and they must maintain the deception, which they do, for several more years. But in the movie, only Tom finds out that their daughter’s real mother is still alive—information that he conceals from his wife.

Thus Isabel lives for years in blissful ignorance, and the carefully constructed psychology of Stedman’s story proceeds, as another critic might put it, into “weepie” territory. The central struggle of the novel, the battle between Isabel and Tom as they both assert their position’s moral superiority over the years, is lost entirely, because for most of the film Isabel doesn’t even know Hannah is alive. Instead, the story becomes all about Tom as he shoulders the knowledge that their happy little world could come apart at any minute, sacrificing his sense of honor for his wife’s happiness. It’s sad, sure, but it’s not interesting, because this version of Isabel, frankly, isn’t very interesting either.

A plot as ludicrous as The Light Between Ocean’s requires an expert hand to pull off, and Stedman manages this in the book by making her characters, in particular her female characters, feel real, in spite of their outlandish circumstances. Isabel, unable to have children but desperate to be a mother, will do anything to keep her baby, even at the expense of a stranger’s happiness or her own husband’s sense of self-worth. Isabel is allowed to be resentful and selfish and unlikable, because without those qualities, the story falls apart.

But Isabel isn’t the only victim of Cianfrance’s alterations. Hannah, played by a very tearful Weisz, is so patient and gentle in the movie as to be laughable. When she finally recovers her daughter, she is all kindness and sweet frustration, a far cry from Stedman’s version of Hannah, who feels betrayed by this 5-year-old who wants nothing to do with her. Movie Hannah croons lullabies. Book Hannah smacks a doll out of her daughter’s hand.

This all comes to a head at the very end of the film: When Isabel and Tom’s crimes finally catch up with them, Hannah offers to speak on their behalf, asking for clemency. “Why would you do that?” asks the local police sergeant in disbelief, echoing exactly what I and surely others in the theater were thinking. “Because you only have to forgive once,” Weisz answers beatifically, gazing at a photo of her dead husband. In the novel, when the sergeant suggests that Hannah testify on behalf of her child’s kidnappers, she throws a vase at him.

Plumb’s essay concludes with a happy ending of its own: the film’s warm reception in Paris, where “real people” (not critics, who, naturally, are automatons) appreciated it for what it was. “Everyone was sending Derek words of appreciation, and stories of audiences sobbing all across America.” And no wonder—Cianfrance’s film sacrifices the nuance of its source material and populates the story instead with saints and martyrs who are the victims of fate rather than their own actions. Who wouldn’t weep?