The second season of Mr. Robot ended up with a bang but not a boom. In the finale, “Python,” mysterious Phase 2 of fsociety’s plan to wipe the world’s financial slate clean turns out to be the anti-corporate equivalent of Oklahoma City. Unbeknownst to his conscious mind, Elliot’s alter ego has been plotting with the Chinese hackers of the Dark Army and the not-so-late Tyrell Wellick to blow up the building where E-Corp is gathering their paper records, attempting to rebuild the database that the 5/9 hack wiped clean. This would, naturally, kill everyone in the building, but Elliot’s the only one who seems to have any compunction about sacrificing those lives for the greater good. He tries to undo the hack into E-Corp’s systems that will turn the building’s backup power supply into an explosive device, but Mr. Robot is already a step ahead of him: He left Tyrell strict instructions to shoot anyone who got in his way, even Elliot himself, and he dutifully follows through, leaving Elliot bleeding on a warehouse floor.

Also bleeding on the floor: Tyrell’s not-widow Joanna, who’s never let go of the possibility that her vanished husband was still alive. The messages she’d apparently been receiving from him turn out to come from Scott Knowles, the E-Corp exec whose wife Tyrell strangled in the first season, but even that hasn’t diluted Joanna’s chilly devotion: She baits Scott into beating her, exulting in the death of his wife and their “fetus corpse,” then coaxes her current lover into framing Scott for his wife’s murder. Meanwhile, FBI agent Dom DiPierro reveals to Elliot’s sister, Darlene, that the bureau has been onto fsociety for months, patiently keeping tabs on them and building its case, which seems to leave Darlene no choice but to turn on her former comrades, and we learn, finally, that Angela, who was persuaded into dropping her personal vendetta against E-Corp, is now firmly allied with Tyrell and the Dark Army.

That’s a lot of shifting alliances and counteralliances to process and to very little end. Mr. Robot’s creator Sam Esmail has said the show was conceived as a feature film, with the first season roughly corresponding to the script’s first act, and though the story has no doubt expanded since then—Esmail now says he envisions the series running for four or five seasons—the second felt much like a three-act story’s middle third, mechanically moving pieces around the board so they’re in place for the denouement. The relationships built in the first season were largely sidelined as characters spun off into their own disconnected stories or were artlessly placed aside until they were needed again.

Even diehard Mr. Robot fans had trouble keeping the story straight, and Esmail and co. seemed to devote more time to working out ostentatious camera moves than the piddling mechanics of plot. With its penchant for off-center framing and maximum headroom, the show’s visual style was invigorating at first, but in the second season, it became more a fetish than a tool, an idea repeated but not developed. In one scene involving the Chinese hacker Whiterose, the characters were placed so low in the frame that the subtitles had to be relocated to the top of the screen, at which point the stylistic gimmick becomes an active distraction.

The news that Esmail would direct every episode of Mr. Robot’s second season could have been a breakthrough in auteurist TV, but it ended up as a cautionary tale in self-indulgence, a kitchen with too few cooks instead of too many. Although “Python,” which was conceived as the second half of a two-parter, was oddly truncated, most of the season’s episodes ran long, with no apparent reason beyond a lack of oversight. Between Dark Army shootouts and Taser mishaps, the show’s body count escalated dramatically, but upping the action quotient felt less like an evolution of the story than a contrived attempt to enliven what was mostly a string of distended dialogue scenes that could have made their point in half the time. Like Fargo’s monologue-heavy second season, Mr. Robot’s creaked under the weight of its own self-conscious prestige, equating length and ponderousness with importance.

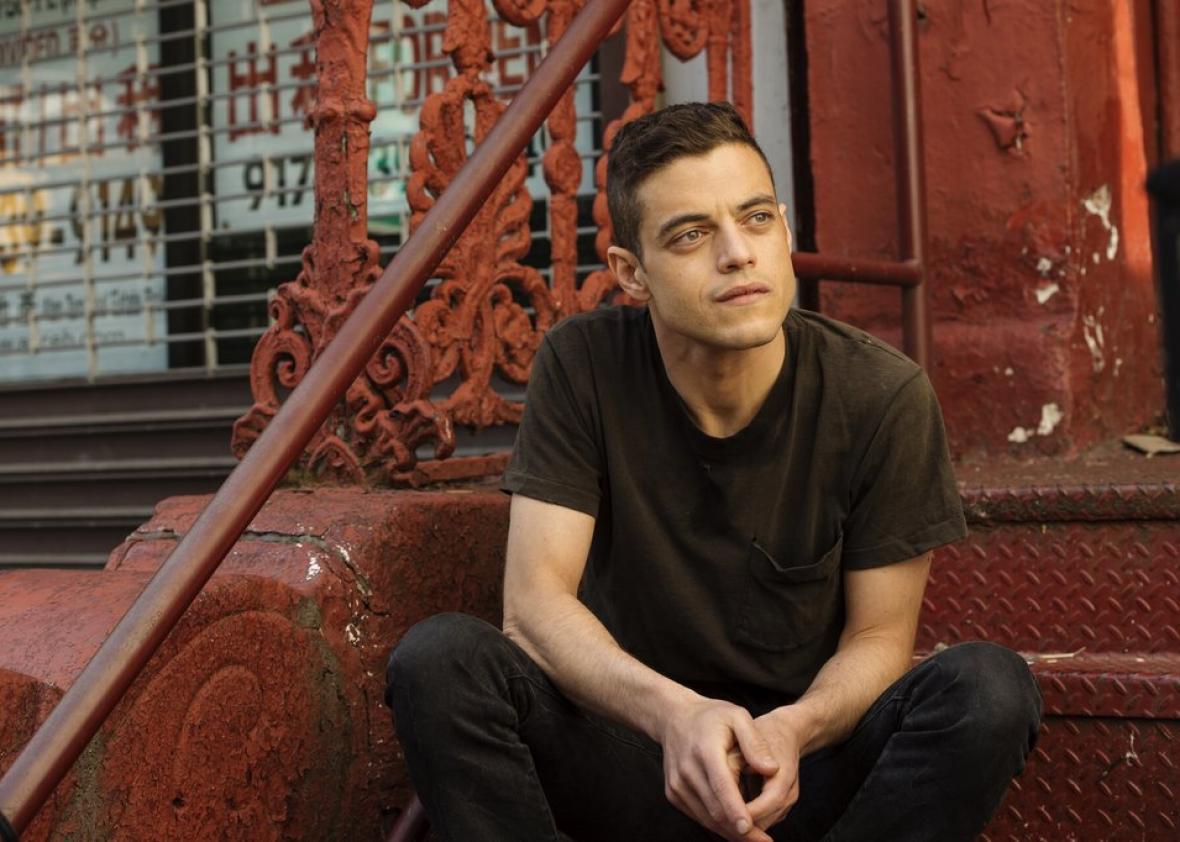

It would be one thing if Esmail and co. were laying out genuinely provocative ideas, but too often, its artiness was draped over pseudo-profundities that could have issued from the mouth of a teenage pothead. Rami Malek deserves the Emmy he won Sunday night for many reasons, but one of them is being able to utter dialogue like this with a straight face: “It’s one thing to question your mind. It’s another to question your eyes and ears. But then again, isn’t it all the same?” So deep, dude.

As Darlene smirked her way through the FBI’s interrogation, a testy agent warned her, “You’re not on some TV show. This isn’t Burn Notice”—a cheeky slap at what had been one of USA’s signature shows. But Esmail couldn’t risk viewers missing the joke, so he doubled down, and then did it again: “There are no blue skies for you,” the agent went on, referencing the in-house term for the network’s formerly sunny programming, and then took a shot at its old “Characters Welcome” slogan. “Characters like you are not welcome here.” Do you get it? What about now? Now?

That goes beyond cheek into cool-kid posturing, smugly asserting Mr. Robot’s status as the “edgy” outlier among USA’s roster, even though the ads for the upcoming Falling Rain and Eyewitness that aired during “Python” show it’s hardly alone anymore. Week after week, it desperately shores up its bonafides, dropping one (bleeped) F-bomb after another; the finale even threw in a C-word for extra credit. Perhaps it’s not an ironclad rule that a show that uses songs from Kraftwerk and Kenny Rogers in the same episode is trying too hard, but it sure feels like it should be. Esmail can shamelessly rip off Twin Peaks all he wants, but David Lynch’s weirdness is too genuine to self-advertise. Malek’s performance has lost none of its intensity, but Elliot has become a static and reactive character; he spent most of the second season getting the stuffing knocked out of him. Watching Mr. Robot’s started to feel like being pummeled, too, suffering through sophomoric philosophy for the sake of a pithy line or a nifty twist. When there’s so much TV to choose from, that’s not enough.