They probably don’t remember, but the kids at my high school got to watch me fall in love with Edward Albee.

I was cast (25 years too young, of course) in the role of Peter in my magnet school’s production of The Zoo Story, the one-act that was Albee’s breakthrough as a dramatist after well-received productions in Berlin and at New York’s Provincetown Playhouse in 1959. In The Zoo Story, the middle-aged family man Peter is trying to read on a Central Park bench when he’s approached by a disturbed, voluble stranger named Jerry. Jerry needles Peter with intrusive questions before letting fly with a hilarious and terrifying stream of TMI that climaxes with “THE STORY OF JERRY AND THE DOG,” an anecdote of his attempt to connect with, and later to kill, the pooch belonging to the landlady of his rundown boardinghouse. “THE STORY OF JERRY AND THE DOG” goes on for six pages, which means the actor playing Jerry needs great breath-control and the actor playing Peter better be pretty good at listening. This was not a problem for me; I was rapt. We did the show ten or fifteen times, but when Jerry’s story reaches its climax—

I have learned that neither kindness nor cruelty by themselves, independent of each other, creates any effect beyond themselves; and I have learned that the two combined, together, at the same time, are the teaching emotion.

—it never failed to raise every hair on the back of my neck.

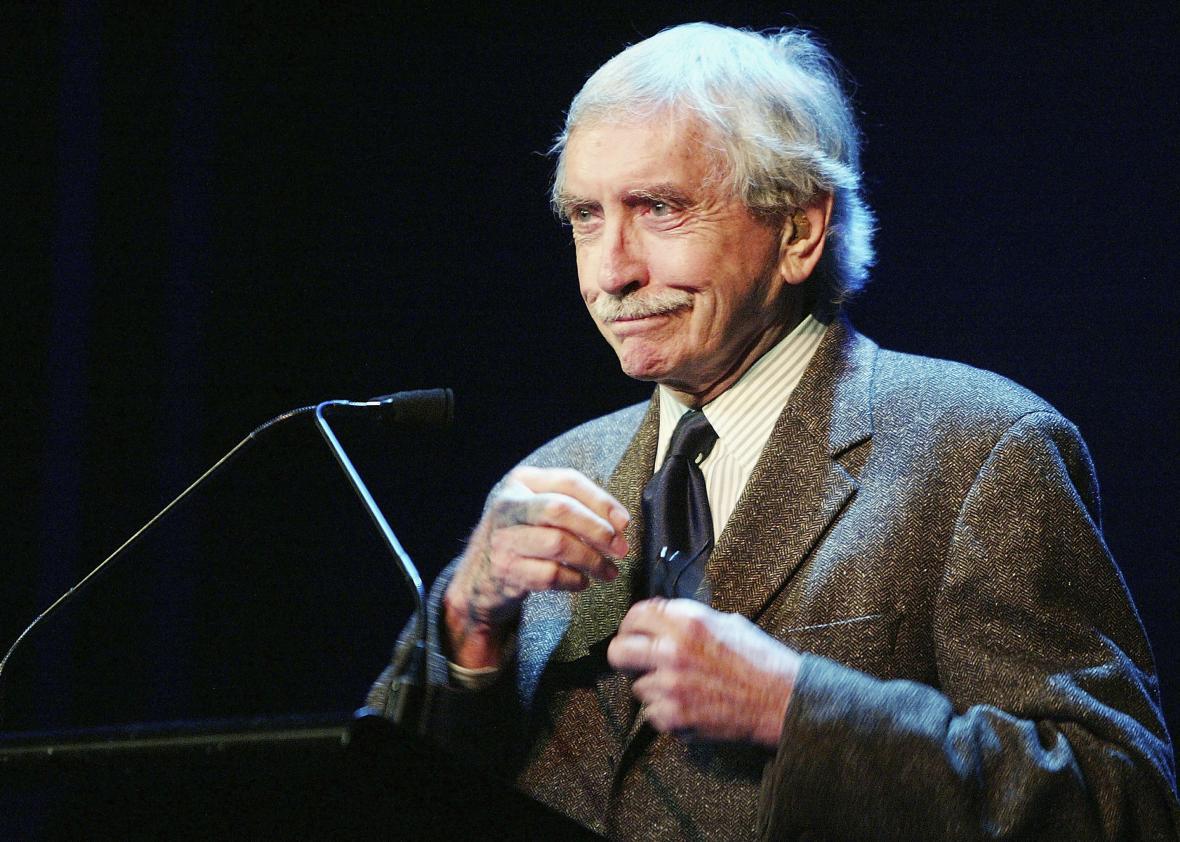

“THE STORY OF JERRY AND THE DOG” would prove to be something of a thesis statement for Albee, who died Friday at the age of 88. He went on to write another thirty plays (winning three Pulitzer Prizes in the process), and less than ten years into his career he was already regarded as a giant of American playwriting. This reputation survived poorly received plays in his early heyday like Tiny Alice that are now widely respected. And it survived a long stretch of critical and commercial flops in the 1970s and 1980s. In 1990 Albee emerged into a triumphant late-career renaissance that brought the world Three Tall Women, The Play About The Baby, and The Goat, or Who Is Sylvia? And that theme of kindness and cruelty acting in tandem with one another—that “teaching emotion”—was an idea that recurred in his work again and again.

It’s there in the closing moments of Albee’s legendary, frequently revived hit Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? (filmed by Mike Nichols in 1966) as George sings softly to his wife Martha after an evening of emotional warfare. It’s there his late-career Broadway success The Goat, or Who Is Sylvia?, as the long-married Stevie’s reaction to her husband Martin’s highly unconventional infidelity (with, yes, a goat) moves from a lacerating verbal takedown in Scene 2 to a stunning final tableaux of slaughter motivated by love.

The teaching emotion appears most vividly in the emotional climax of Albee’s 1966 Pulitzer Prize winner A Delicate Balance. Balance chronicles a series of intrusions, over the course of a weekend, into the unhappy married life of aging suburbanites Agnes and Tobias: their daughter Julia, whose fourth marriage is on the rocks. Agnes’s sardonic, hard-drinking sister Claire. Most disturbing is the unexpected arrival of Harry and Edna, the couple Agnes and Tobias have long considered their closest friends. As Harry and Edna tell it, they were just sitting at home alone when they got… scared. Indefinably scared. Too scared to stay in their house. And now they’d like to sleep over.

This remarkable set-up on Albee’s part—a near-retirement-age couple who are frightened like children of their own quiet house—is a textbook example of how he brought the European absurdist sensibility of Beckett and Ionesco into the American living-room drama. But even more intriguing is where it leads. Harry and Edna push all boundaries of friendship, going as far as trying to move in with Agnes and Tobias, before caving under pressure from Julia and Claire to leave. In a private moment, Harry admits to Tobias that if their positions were reversed, he wouldn’t take Tobias and Agnes in. “You don’t want us, do you, Toby?” he asks.

Tobias’s breathtaking answer—explicitly described as an “aria” in the text—may be Albee’s greatest distillation of kindness and cruelty, as this long-emotionally-repressed man rails at his friend of twenty years:

I DON’T WANT YOU HERE! YOU ASKED?! NO! I DON’T! BUT BY CHRIST YOU’RE GOING TO STAY HERE! … YOU BRING YOUR TERROR AND YOU COME IN HERE AND YOU LIVE WITH US! YOU BRING YOUR PLAGUE! YOU STAY WITH US! I DON’T WANT YOU HERE! I DON’T LOVE YOU! BUT BY GOD… YOU STAY!

Tobias’s cruelty, his disavowal of love for his oldest friend, is coupled with yearning for connection that’s as moving as it is preposterous: Harry and Edna’s absurd presence in his house is an opportunity, a chance at some twisted version of community, at an end to a life of corrosive habit and isolation.

It’s noteworthy that many of Albee’s most toxic couples are still together at the final curtain. There’s something binding them together that runs deeper than their mutual abuse of one another. The terrible truths they tell one another are an attempt to claw their way out of a life of deadening delusion. They’re trying to teach each other.

A gay playwright who rarely wrote on gay themes, a control freak who accompanied nearly every line in his scripts with detailed instructions on how to deliver it, and a testy artist unwilling to cater even slightly to audience tastes, Edward Albee was one of the most fearless, experimental, and uncompromising artists in American life. I see his influence everywhere, in every TV show that pushes its audience into uncomfortable laughter, in every film that probes the raw spots of a charged love affair. And I see his influence on the stage, in the work of every playwright who explores our human ability to use language to dazzle, to charm, to cut and to repair one another. I have no doubt that every year for decades to come new teenagers playing comically young Peters on high school stages will listen quietly as “THE STORY OF JERRY AND THE DOG” blows their minds again and again.