Originally released a decade after the fall of the Berlin Wall, Brad Bird’s The Iron Giant was praised as an anti-war, anti-gun fable—or, less frequently, damned for being the same. Set in a coastal Maine town at the height of the Red Scare, the movie updates and revises the era’s own cinematic nightmares, from alien invasion to nuclear holocaust. Seventeen years later, the movie—the director’s cut of which was released this week—has been enshrined as a cult classic, an animated children’s flick that gives their parents plenty to think about and cry over. But with the Cold War now more of a distant memory than a half-healed wound, the movie looks very different, especially in light of Bird’s subsequent career.

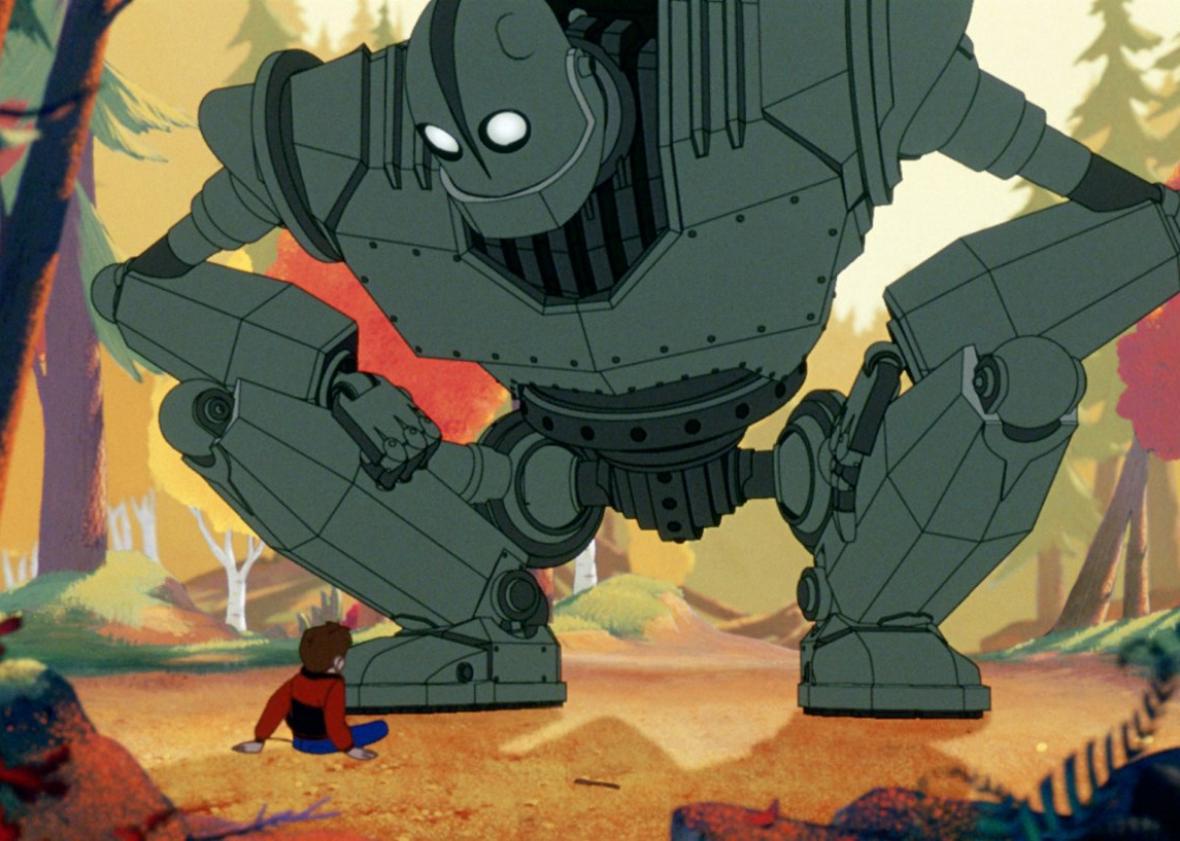

The story begins, as so many 1950s movies do, with a foreign object crashing to earth: a giant metal robot, linked in the opening shot to the looming specter of Sputnik, an omnipresent reminder of the Soviet Union’s advantage in the space race. The Giant, who is never named, is discovered in the woods by a young boy named Hogarth Hughes (voiced by Eli Marienthal), who takes the sentient but simple-minded contraption under his wing, teaching him how to speak—which he does, in a rusty croak supplied by Vin Diesel—and how to stay hidden, correctly reasoning that his appearance could cause a panic, or worse.

It’s when Hogarth’s education takes on a moral component that The Iron Giant gets really interesting. After they see a deer killed by hunters, Hogarth explains the nature of morality and its place in the cycle of life: “It’s bad to kill,” he tells the Giant, “but it’s not bad to die.” The Giant, who’s effectively a child, is rattled by the idea of mortality, but Hogarth comforts him with the notion that their souls will live on—and yes, he’s sure the Giant has one. “You’re made of metal,” Hogarth reasons, “but you have feelings, and you think about things, and that means you have a soul.”

The assertion that the Giant has a soul is where the idea that The Iron Giant is at heart a movie about war or weapons starts to break down. After he begins to remember his previous existence as an alien killing machine, the Giant concludes, “I am a gun,” but that’s only a provisional understanding. One of the two new scenes added to the film’s Signature Edition, conceived for the 1999 release but not completed until last year, is a nightmare in which the Giant marches through the flaming ruins of an alien city amid an army of identical figures. (Both the Signature Edition and the original cut are available on Warner Bros.’ new Blu-ray.) He was a gun—or, more to the point, a weapon of mass destruction—but now he’s developed a conscience, and guns don’t feel guilt.

Is the Giant, as one angry New York Post writer argued back in the day, a liberal Hollywood embodiment of the misunderstood USSR? “The Iron Giant seeks peaceful coexistence and will only use his sophisticated weaponry in self-defense,” wrote the Post’s Rod Dreher in 1999. “That’s what Soviet apologists said about the U.S.S.R., too.”

The restored dream sequence, which shows the Giant walking in lockstep with dozens of identical robots, might fitfully bolster the idea that he’s a Communist stand-in, but it’s only when he’s separated from the collective that the Giant’s nature becomes clear. At least on Earth, he’s like one of the extraordinary heroes who populate Bird’s The Incredibles, Ratatouille, and Tomorrowland—and like them, he’s eventually called upon to save the self-destructive masses from themselves. But where The Incredibles’ “supers” are unfairly persecuted by vengeful normals, the movie’s humans have good reason to fear the Giant, even if they don’t know it: He was built to destroy, and not only in self-defense. On Earth, he’s like a newborn, but he had another life before that, and the capacity to kill is still part of his programming.

The framework that is most helpful in contextualizing the Giant goes back way before the Cold War: This is really a story about the dark side of human nature—or, more specifically, about sin. The movie explicitly frames the Giant as a Christ figure in its final act, complete with a luminous cross hanging in the heavens, and it sets up a kind of Manichean dualism in the form of the comic books Hogarth shows the giant: One cover depicts “Atomo, the Metal Menace”; the other shows Superman. (Perhaps not surprisingly, Christian critics seem to be the only ones to have written about this aspect at length.) The Giant’s earthly rebirth doesn’t erase his past evils, and they still have to be atoned for, even if they weren’t committed by choice. “You are who you choose to be,” Hogarth advises him, and the Giant chooses to be Superman.

It’s a choice Bird’s subsequent heroes haven’t really gotten to make: Ratouille’s Rémy can cook or not cook, Mr. Incredible can save the world or let it take care of itself, but they’ll always have greatness in them. The Giant has to choose to be great, and it’s that choice that makes his salvation meaningful. Bird has said that the question that prompted The Iron Giant was “What if a gun had a soul?” The movie’s answer is that it wouldn’t be a gun anymore.