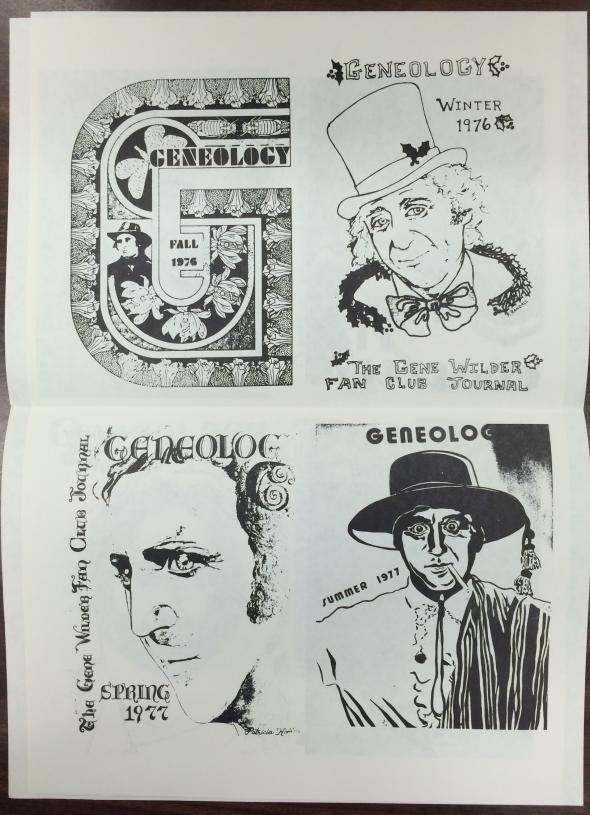

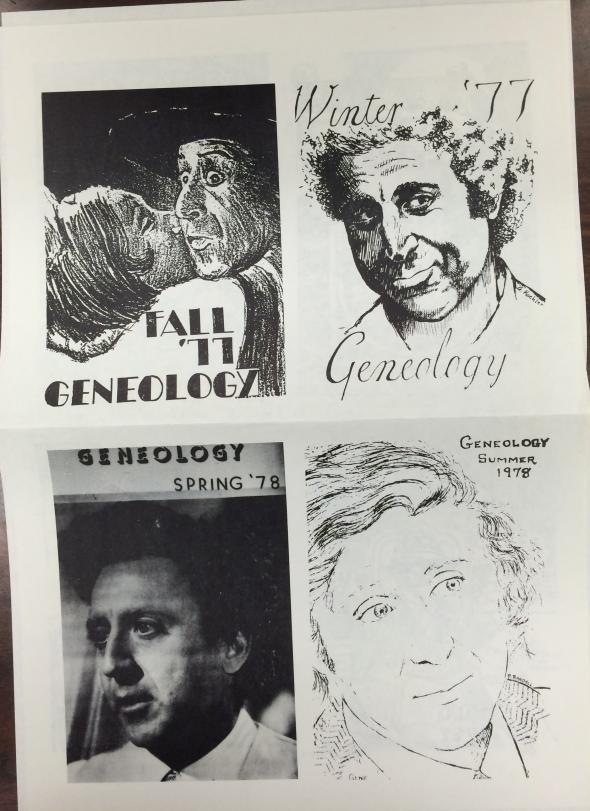

Long before he became Gene Wilder, Jerome Silberman enrolled at the University of Iowa, where he later told a fan he went “to play football—All American.” His dry joke, which took an uncomfortably long moment to land, is recorded on a cassette in the university’s archives, where he left eight boxes of scripts, letters, photographs and other materials that span his career. After Wilder’s death, I dug through the archives at University of Iowa, where I’m a professor in the English department. I found troves of material, from the meticulous fourth draft of Young Frankenstein, to his manic revisions to unproduced scripts like Dying for A Laugh. The Wilder archives document a historic talent. But nothing illustrates what Wilder’s career meant better than the materials produced by a group of Wilder superfans—interviews, books of poetry about his “twinkly eyes and fuzzy hair,” and a hand-copied zine called Geneology that ran from 1976 until at least 1980.

University of Iowa archives

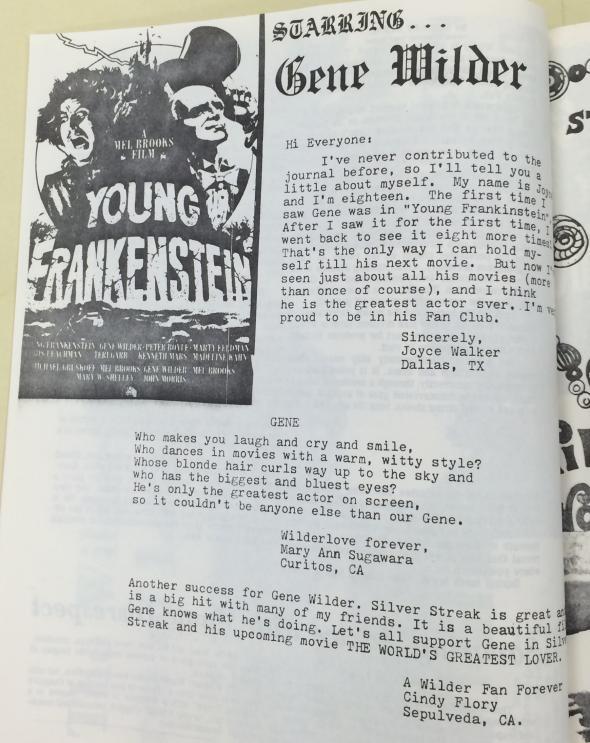

There have been many fan clubs. (Our archives also hold a fine collection of the Bee Gees Quarterly and the David Cassidy Info Bulletin.) But I’m not sure any of them have been so aggressively devoted to the outsider as Geneology, and this says something both about Wilder and the community that organized itself around him. A typical celebratory article is titled “The Loser Who Beat the System.” And for anyone who grew up in a perpetual awkward phase it is hard not to feel a twinge of solidarity with the 18-year-old from Dallas who admits she’s seen “Young Frankinstein [sic] eight times, and that’s the only way I can hold my-self till his next movie.”

University of Iowa archives

As America made its hard right turn into the 1980s, Geneology celebrated irony and fragility. Its DIY ethos anticipates a subculture that has made Wilder the reigning king of internet memes. Between Geneology’s Xeroxed covers, men, women, and teenagers proclaimed their love of Wilder and devotion to a community of self-identified misfits. These were Wilder’s diehard fans: From tiny towns in California, Maryland, and Wisconsin they sent poems, crosswords, sketches, and hand-drawn trivia games such as “In Which Movie Did Gene Wear Each of These Hats?” A typical poem declared Wilder “vulnerable / When others hold back.” Another contributor admitted with disarming ease that she was “too emotional and could not deal with a rational world.”

University of Iowa archives

Could this possibly be healthy? I managed to track down the club’s founder, president, and guiding spirit, Judith Nathanson, now 70. “I wish I still had any of those things,” she said as she took the phone from her husband, who sounded a little weary of Wilder. “But this was before the internet, before computers, before any of that. We were just making copies and putting them in the mail.” She was shocked to hear that Geneology and the fan club materials still existed and had been carefully catalogued and filed by a team of archivists. But her enthusiasm for Wilder had not dimmed since the day she founded the club as a young theater student and teacher. And she had been mourning his loss all week.

University of Iowa archives

She contacted Wilder in the early 1970s to ask about starting a fan club, “and as soon as we did, letters started pouring in from all over the country, all over the world.” What she believes they saw in Wilder, beneath the madcap energy, was an essential shyness that he somehow conveyed in the most public way possible. In his moments of quiet, Wilder made himself available to fans who could fill in the blanks with their own angst.

That’s at least what they did in Geneology, in the most literal way. Easily moving between rank amateurism and astonishing polish, the magazine’s contributors poured out their hearts to one another, year after year. Enthusiasm for their subject was the only criteria for admission. They sometimes signed their letters “sincerely.” But their most common valediction, and one that sums up box upon box of materials, was “Wilderlove forever.”