As audiences expressed disappointment at the slate of sophomore dramas and cried foul at new prestige projects, summer TV quietly yielded a major success story this year. Despite the surrounding noise, Greenleaf—the OWN family drama focused on a powerful Memphis, Tennessee, megachurch—set ratings records for its network week by week and more than doubled the live (and three-day) viewership average of relatively buzzed-about summer shows such as USA’s Mr. Robot and Lifetime’s UnReal. Of all summer premieres, it’s currently—and likely to remain—the most watched among total viewers and women.

Yet Greenleaf, like many popular cable dramas, has been largely critically ignored, a fate that often befalls the frothy fare of networks such as USA, TNT, and OWN itself. Possibly because of its soapy trappings, and more likely because of its popularity with an underrepresented audience, the series has struggled to penetrate the cultural conversation as other flawed but promising first-year dramas have. This summer has been in desperate need of breakouts—in the field of recent hourlong newcomers, there have been far more misses than hits—and Greenleaf meets the standard in more ways than one. In 13 episodes, the series has introduced a rich milieu of characters otherwise unknown to TV drama, while also presenting creative and forceful arguments about faith, family, and community.

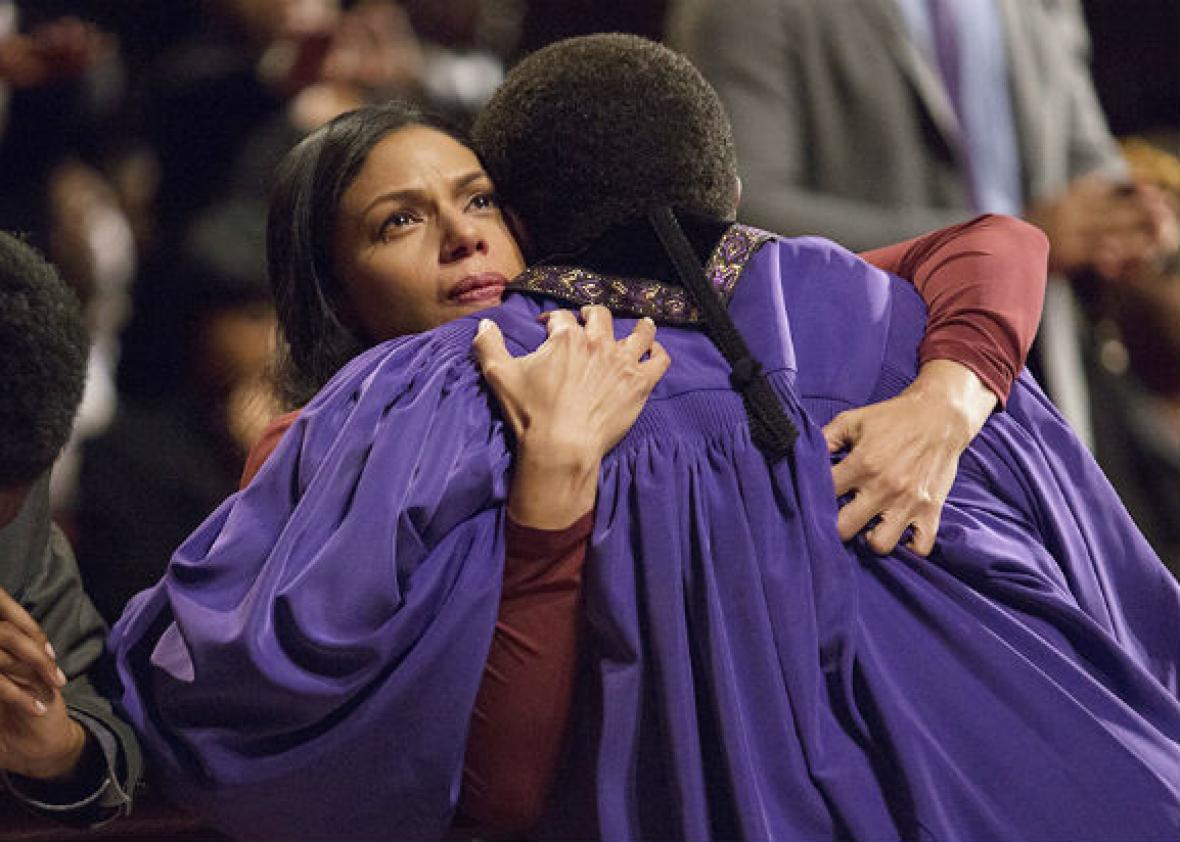

Greenleaf treats the religiosity of its devout characters with curiosity and respect, rather than as a punchline. The pilot opens on Grace Greenleaf (Merle Dandridge), the “prodigal daughter” who escaped her family and its ghosts as a young adult, returning home for her sister’s untimely funeral. (She died by suicide.) We’re given hints about Grace’s rare gift for preaching—inherited from her father, Bishop James Greenleaf (Keith David)—and her subsequent loss of belief in its value. Growing up, she was exposed to sexual abuse cover-ups, morally questionable behavior from her revered parents, and confluences of faith, leadership, and politics in the church. Upon her return, she dredges up family secrets—barely a minute after her mother, Lady Mae (Lynn Whitfield), icily warns her, “Promise me you’re not here to sow discord in the fields of my peace”—before plotting a swift departure. That is, until she attends church. Listening to her father preaching, Grace experiences catharsis, the congregation roaring in approval around her, her father’s voice bellowing with warmth. She decides to stay in Memphis on the condition that she reform the church.

The tension between Grace’s struggle with the church and her acceptance of its spiritual nourishment, is at the heart of Greenleaf. The series is fundamentally an ensemble work, a family chronicle that deconstructs common TV tropes about infidelity and sexuality as a way to get at more complicated ideas—namely, about how those subjects intersect with faith. The show juxtaposes the way faith fortifies people—giving them purpose, a sense of community, or general guidance—with the way it confines them. Its characters act against their better judgment throughout: An aspiring pastor cheats on his wife, a closeted newlywed keeps his secret as baby-making plans commence, and a revered bishop lives lavishly—and not entirely ethically—while championing a black community wrought by racial inequalities.

In the canon of quality dramatic television, serious explorations of everyday religion are few and far between. HBO’s late Big Love and Hulu’s newbie The Path rank among the more prominent examples, but their depictions of cultlike behavior and grand conspiracies are far removed from the minutiae of daily life for most people; others, like The Leftovers and Rectify, are deeply spiritual but less focused on the institutional aspects of belief. In this era of Peak TV, religion—so central in various corners of American life—would indeed seem due for a more grounded, emotionally realistic treatment on the small screen. And Greenleaf confronts this head on. The show contends with organized Christianity’s limitations and shortcomings without condemning its followers; it questions the function of the modern church with genuine curiosity, as opposed to presumptive cynicism.

This is best exemplified by the show’s take on Black Lives Matter, which might seem arbitrary at first glance. A running subplot involves the Memphis community’s vilification of David Nelson, a black cop who killed a young, unarmed black man and is facing a potential indictment. The city government presses James to embrace Nelson as one of the church’s—and community’s—own, even offering financial and property incentives to do so. Grace herself believes in the church’s role as a healing space for everyone, including a controversial figure like Nelson. But the Memphis community rejects him, and Lady Mae and other family members similarly beg James not to stand beside Nelson. James brings him in anyway, however, swayed by the material benefits in doing so as well as the notion that the church should be welcome to all. Of course, it doesn’t go too well. James makes the mistake of ignoring his political stature—that, as a leader of a disenfranchised community, he has placed himself at the center of an institutional crisis without an easy remedy.

Greenleaf demonstrates a keen understanding of the nuances of faith as an institution, particularly as it has historically related to politics and race. The show doesn’t shy away from the hypocrisies and inconsistencies of Christianity—granted, sometimes it indulges in them a bit too much. But overall, it represents the church as an imperfect but invaluable gathering place for singing and healing, for self-expression and discourse. And this is what makes Greenleaf’s textured optimism ring true.