Virtually every film in modern memory ends with some variation of the same disclaimer: “This is a work of fiction. Any similarity to actual persons, living or dead, or actual events, is purely coincidental.” The cut-and-paste legal rider must be the most boring thing in every movie that features it. Who knew its origins were so lurid?

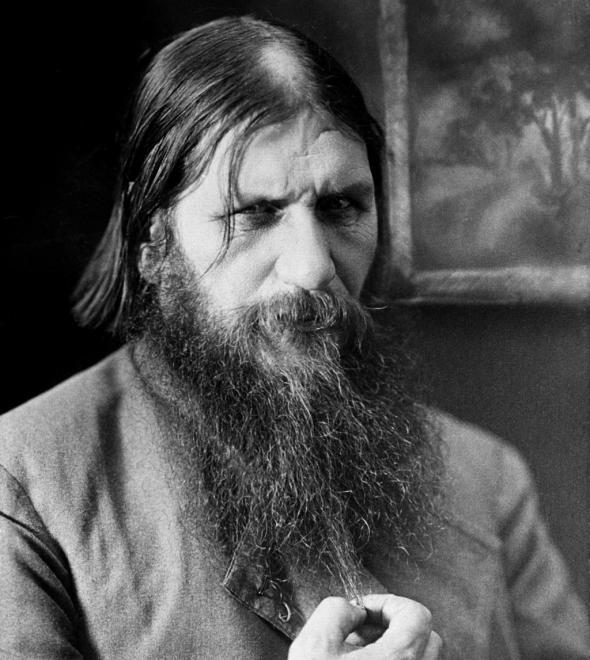

For that bit of boilerplate, we can indirectly thank none other than Grigori Rasputin, the famously hard-to-assassinate Russian mystic and intimate of the last, doomed Romanovs. It all started when an exiled Russian prince sued MGM in 1933 over the studio’s Rasputin biopic, claiming that the American production did not accurately depict Rasputin’s murder. And the prince ought to have known, having murdered him.

Here’s the story. In 1916, the fabulously wealthy, Oxford-educated Prince Felix Yusupov was one of several Russian aristocrats agonizing over the unseemly influence that Rasputin—the magical healer, charismatic lech, and peasant—had over the czar and, particularly, the czarina. In December, Yusupov invited Rasputin to his palace, where he offered him cyanide-laced cakes and then shot him.

Although the czarina was distraught, the czar let Yusupov off lightly, exiling the prince and his wife Irina. (In doing so, he inadvertently spared them from the impending slaughter of the revolution.)

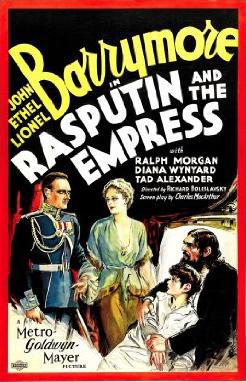

Sixteen years later, MGM produced Rasputin and the Empress, based on those events. Its big coup was casting the three Barrymore siblings—stars of stage and silent film—in the lead roles. Lionel played Rasputin, Ethel the czarina, and John (grandfather of Drew) was “Prince Paul Chegodieff,” a composite, who murders Rasputin.

Yusupov, now penniless in Paris, heard about the film and thought it defamatory. He argued audiences would recognize him in the fictional assassin—in part because he’d publicly cashed in on his infamy, penning a braggy memoir about killing Rasputin. He wasn’t wrong: The New York Times, in its review, noted that Chegodieff was “really intended to represent [Yusupov].”

But having copped to being a murderer, Yusupov couldn’t build much of a libel case. Instead, he alleged that Rasputin and the Empress in fact defamed his wife.

In the film, Chegodieff’s wife is “Princess Natasha,” a supporter of Rasputin. But the mystic, wary of her husband, hypnotizes and rapes her, rendering Natasha—by his logic, with which she agrees—unfit to be a wife. Yusupov contended that as viewers would equate Chegodieff with Yusupov, so would they link Natasha with Irina. But while Yusupov was portrayed more or less accurately, Irina and Rasputin had never met. (The scene also libeled Rasputin, but him being dead, you could say anything, then as now: “Rasputin sucks,” “Rasputin liked to caress his big beard and give it little kisses,” etc.)

An MGM researcher had pointed out this factual discrepancy to the studio during production and warned that the Yusupovs could sue; the studio fired her. MGM was satisfied, dramatically, with the rape scene, despite there being no basis for it in real life. If it was shock they were interested in, one could imagine them constructing a similar scene around Rasputin and the czarina—about whom there were prurient rumors, which Rasputin himself encouraged by whipping his dick out in a restaurant and boasting of giving it to “the old girl”—but MGM couldn’t do that after casting a real-life brother and sister in those roles.

Poster via Wikimedia Commons

Irina Yusupov sued the studio, and the jury found in her favor, awarding her £25,000, or about $125,000. MGM had to take the film out of circulation for decades and purge the offending scene for all time.

What proved to be MGM’s undoing was its lack of deniability. Unwisely, they’d prefaced the film with this: “This concerns the destruction of an empire … A few of the characters are still alive—the rest met death by violence.” From that, audiences could logically infer that the Yusupovs, being the only relevant characters still alive, were represented as the Chegodieffs.

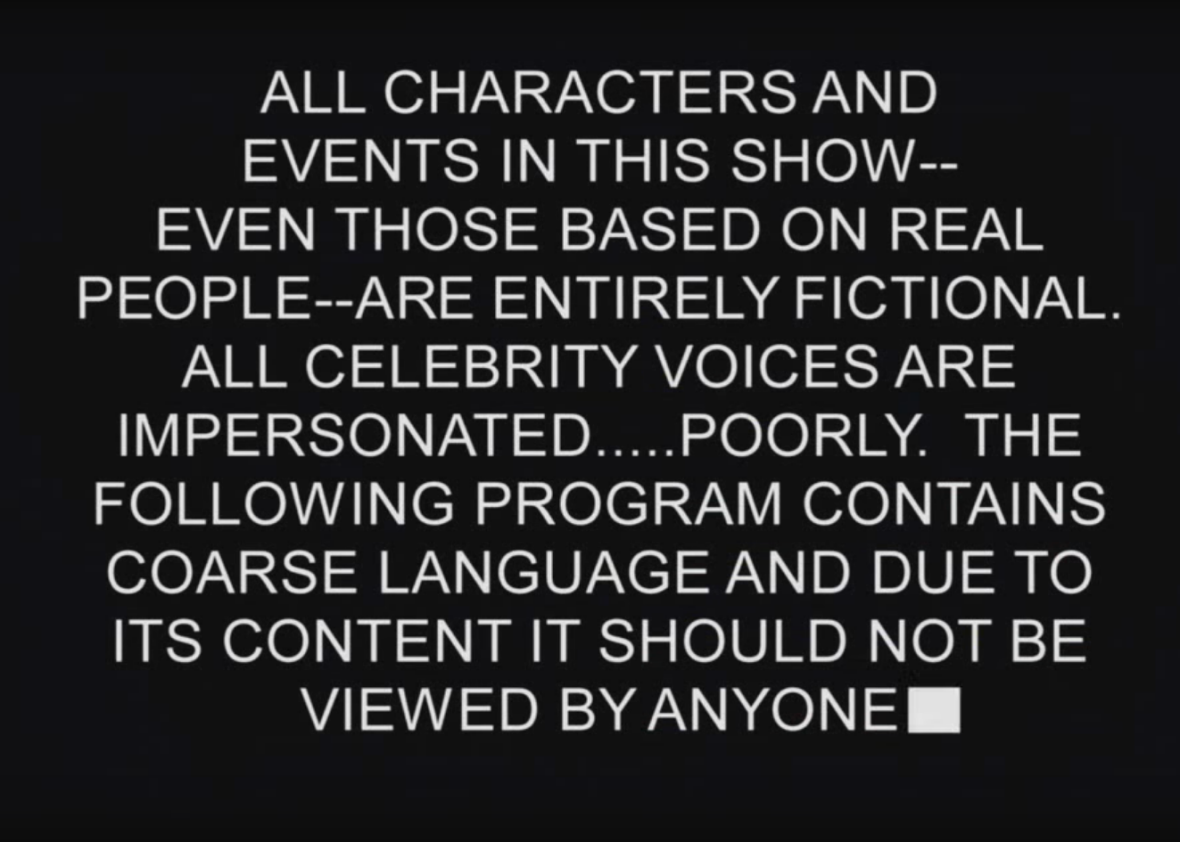

A justice in the case told MGM that the studio might have stood a better chance had they incorporated a disclaimer stating the exact opposite: that the film was not intended as an accurate portrayal of real people or events.

Apparently overcautious in the wake of the landmark lawsuit, the film industry slapped that wording on everything. For decades, films disclaimed absolutely any relationship to reality—even when it was patently untrue. The Jake LaMotta biopic Raging Bull credits LaMotta as a consultant and cites his memoir as a source text just minutes before asserting that he is the film’s entirely fictional invention.

Comedy Central

It’s only recently that studios have relaxed the disclaimer to allow that certain films are inspired, in part, by real events—maybe that’s because, in 1967, Felix Yusupov finally died. Now, blessedly, you can say whatever you want about him.