Over the weekend, Twitter was in an uproar over the use of the word daddy, a discussion started by Model View Culture founder and CEO Shanley Kane. In a since-deleted series of tweets, Kane wrote:

Don’t have deep psychosexual Freudian and Oedipal trauma/dysfunction? Good for you. Stop appropriating “Daddy.” “Daddy” came from queer leather folk and y’all vanilla ass bitches out here like “yes Daddy” while you have monogamous missionary sex. … you are out here being disrespectful and ahistorical trash. “Daddy” has deep fucking roots in places you have no fucking clue about.

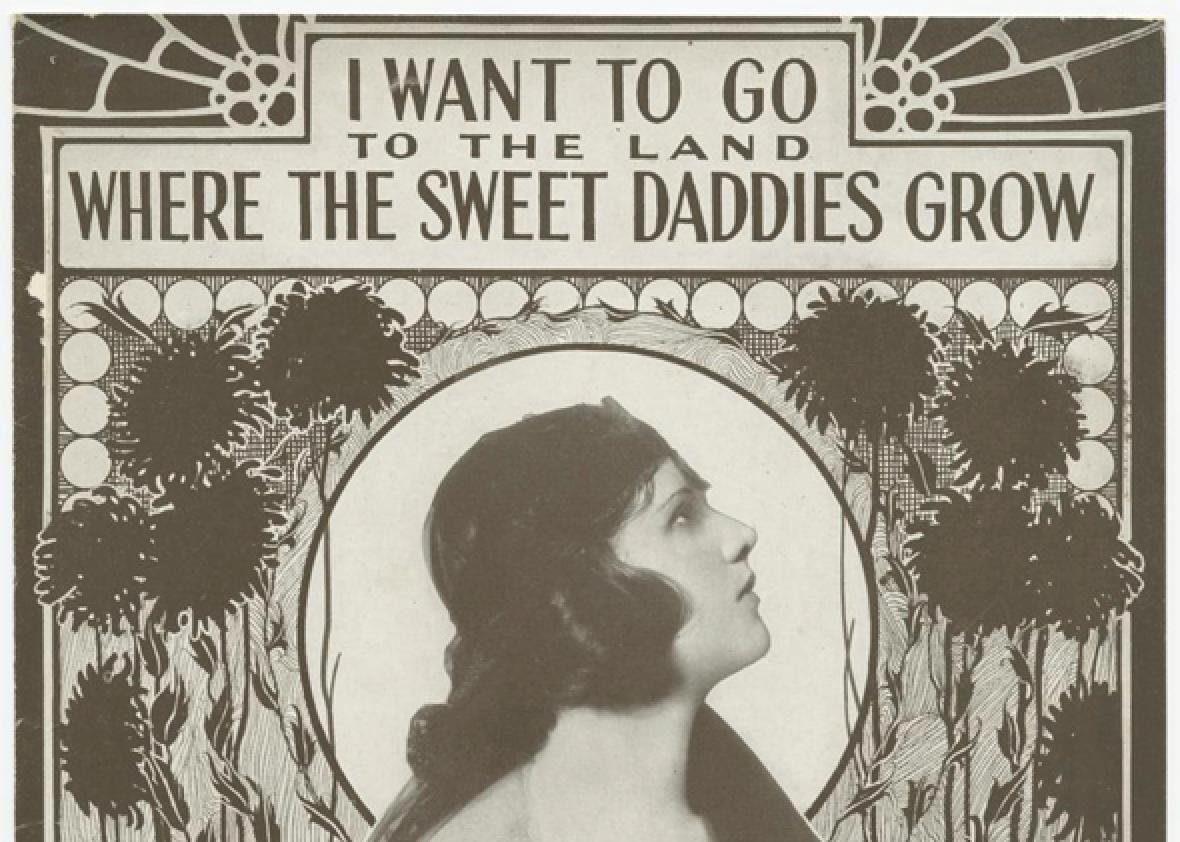

Kane later qualified that “ ‘daddy’ has other contexts/meaning/origins as well, obviously,” which is true: A look at that history would include cultural figures as varied as Thomas Dorsey, Cole Porter, Laurel and Hardy, and Joni Mitchell. But there’s also a long history of people being bothered by the use of the word daddy, which was trendy enough to be newsworthy long before its recent resurgence. Here with her thoughts on the subject is Los Angeles Times reporter Alma Whitaker, as originally published in her column “The Last Word” on May 25, 1922. —Matthew Dessem

The proper study of womankind is man. Wherefore it behooves us to ponder on the psychology of this “dear daddying” that is so much in evidence in the letters from “the other women” in the divorce cases.

They obviously like it, these masculine roamers from hearth and home. In no less than five cases during the last two weeks, Exhibit A has been a bundle of endearing letters—addressed to “Dear Daddy,” to “Darling Daddy,” to “My own beloved Daddy-boy.” And the answers to them signed “Your Daddy,” “Your own true Daddy,” “Your loving Daddicums.”

Even when the lady is not so young as she was, that daddy stuff works like a charm. One almost suspects that the lady of 94, who annexed a young man in his pristine fifties, probably won him with this “daddicums” lure.

It used to be that men liked to be mothered. But that phrase has gone out. It isn’t mothers they want any more, it’s evidently daughters. They don’t even want to be “my king, my prince, my hero” these days—daddy is all-sufficing.

What do you read into that, sisters? Doesn’t it look like a tender longing for authority, a pathetic craving to be enthroned once more in domesticity? A back-to-nature and the superlatives of paternity?

The paternal instinct, the patriarchal complex! With wives insisting on being “comrades,” and children mournfully lacking in that respect due to paternity, with parent-teacher associations made up exclusively of mothers and teachers, the poor chaps are simply driven farther afield to satisfy their yearn for docile affectionate daddying.

That “Mother’s Day” probably has something to answer for too. They rose gallantly enough to the occasion, but as each annual Mother’s Day comes round who knows but what they writhe in the pangs of jealous paternity? After all, there couldn’t have been any mothers but for the daddies. Aren’t they going to get a look in anywhere? “Oh, chase me, girls, and call me Daddy,” is the heartrending plea that must have gone forth to bring out such a wealth of responsiveness.

I don’t exactly see what we can do about it. Perhaps a Father’s Day would help. [Ed. note: Mother’s Day became a national holiday in 1918; Father’s Day in 1972.] Of course we might daddy them, too. We have competed with the “other woman” in more dubious fields ere this—clothes, manners, and make-up for instance. But they are perverse creatures. When they were duly daddies at home, they yearned for the dashing chic and spurious beauty peculiar to elsewhere. Now that they have the spurious beauty and dashing chic at home, they seek the daddying elsewhere.

Man, at best is a contradiction still.