Sausage Party, the raunchy animated film that Seth Rogen, Evan Goldberg, and Jonah Hill have been working on for 10 years, has a very simple premise. Rogen explained it at South by Southwest in March:

People like to project their emotions onto the things around them—onto their toys, onto their cars, onto their pets. That’s what Pixar has done for the last 20 years. So we thought, what would it be like if our food had feelings? And we very quickly realized, oh, that would be fucked up.

Rogen repeated the explanation in a family-friendlier way on Jimmy Kimmel Live! in June:

We love animated movies and we thought one day, like, what if our food had feelings? And then we thought, it’d be super messed up ’cause we eat our food and it would be a horrible existence for them.

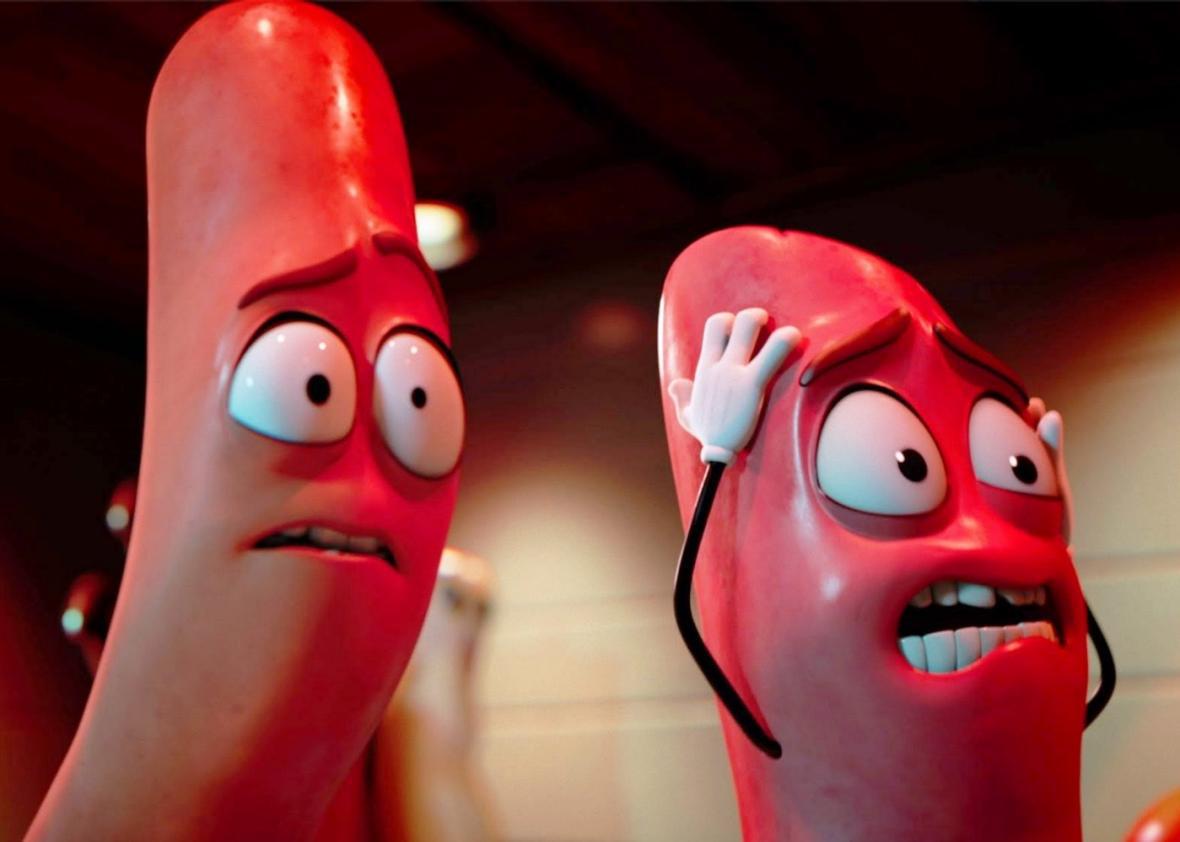

Sausage Party is about an anthropomorphized hot dog, named Frank (voiced by Rogen), who discovers that the humans who visit the grocery store where he lives are not benevolent gods who intend to take him and his food buddies to a paradisiacal “great beyond” but rather are cold-blooded killers who eat food for pleasure and survival. Supporting characters include another hot dog named Barry (Michael Cera), a bun named Brenda (Kristen Wiig), and a bagel named Sammy (Edward Norton). They all have feelings, and it is indeed messed up.

But you know what else is a little messed up? The fact that some of our food actually has feelings, because it was once alive, and that Sausage Party doesn’t acknowledge this. The movie makes no distinction between foods that come from animals—creatures with brains and a capacity for pain—and foods that come from plants. At no point does the film nod to the fact that hot dogs are gelatinous meat sticks composed of a substance that usually comes from cows or pigs, two intelligent and empathetic creatures that often endure “a horrible existence” before they’re slaughtered for meat. When asked by a Vice reporter whether they’d go vegetarian after making the movie, Rogen and Goldberg brushed the question off: “Even vegetables have feelings in our world,” said Rogen. “Vegans are murderers, just like everyone else,” added Goldberg.

Okay, so Sausage Party isn’t really about food—it’s about theology. All the living foodstuffs have different understandings of sin, their relationship with the gods, and their place in the universe, and most of them are stand-ins for recognizable religious and social groups. This is a movie where a stereotypically Jewish bagel and a stereotypically Arab lavash squabble over a shared display case, where German mustard jars spread hateful propaganda about “the juice,” and where a package of grits, voiced by the black actor Craig Robinson, plots to exact revenge against crackers. (Like, actual crackers.) The ethnic stereotypes are a lot more blaring than the fact that the movie has a gaping plot hole where the hot dogs’ backstory should be. For instance: When did Frank, Barry, and their frankfurter brethren acquire consciousness? Presumably it was some time after their antecedent meat scraps emerged from the slaughterhouse; otherwise they’d probably be too traumatized to flirt with buns like Brenda.

Still, it surely says something about Americans’ disconnect from the source of our food that a movie called Sausage Party, in which the main characters are sausages terrorized by humans, doesn’t even once nod at the fact that sausages actually come from creatures terrorized by humans. Sausage Party is an impassioned cry for rationality in the face of narrow-mindedness and superstition. Frank spends most of the movie trying to educate foods who are too sheltered and uncritical to realize that there’s a world of violence beyond the supermarket. Alas, the movie, funny as it often is, has nothing to say about people who are similarly sheltered.