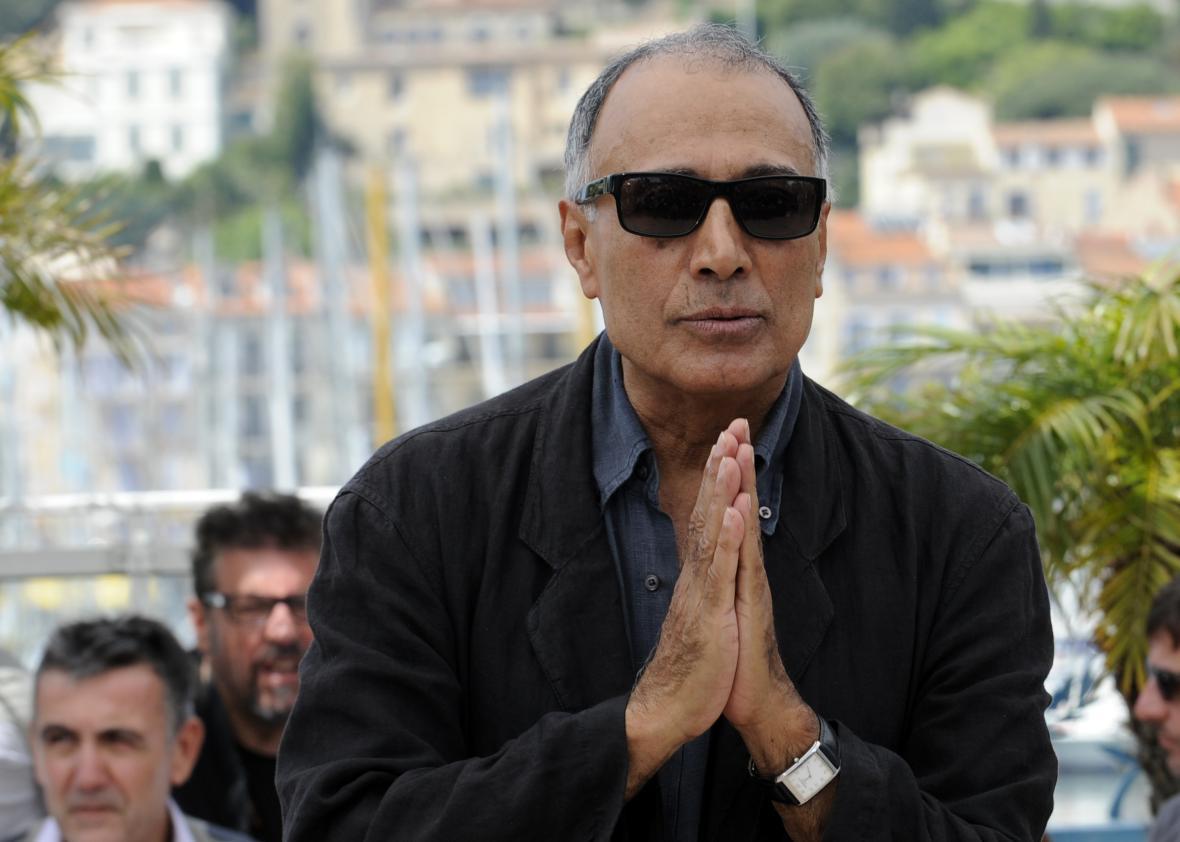

Let’s start with the can rolling down the hill in Close-Up, a 1990 masterpiece by Iranian director Abbas Kiarostami, who died on July 4 at age 76. It would be crass to argue, on the very day after this irreplaceable artist’s disappearance, about which of his movies was the greatest. Different fans will have differing allegiances, and none of them will be wrong. But it would not be hard to argue that Close-Up, a film based on real events and re-enacted in part by those who lived through them, is among the most original and important movies made near (and, in many ways, about) the turn of the 21st century.

Close-Up can best be described as half scripted film, half documentary … or rather, as one-third re-enactment and two-thirds scripted making-of documentary about that re-enactment, plus another third made up of some impossible mix of previously unidentified genres. Really, there’s no describing the unpeelable onion of a movie that is Close-Up. You just have to see it, many times, if possible over a period of several years. (I recommend seeing Kiarostami movies with friends who like to think, talk, look, and listen, four skills at which the director, at his best, excelled.)

There’s much to be said about Kiarostami’s place in the now generationslong wave of innovative cinema pouring out of his native Iran. Alternatively, you could concentrate on his more recent role as a cosmopolitan filmmaker uninterested in claiming a representatively Iranian identity: Over the course of the last few decades, he shot a documentary about children’s education in Uganda, conducted master classes online from Hong Kong, and contributed to an anthology film with the directors Ermanno Olmi and Ken Loach. Kiarostami tended to shy away, both in his work and in press interviews, from addressing politics or ideology head on, though he never hesitated to decry the censorship and mistreatment of his fellow Iranian filmmakers.

Toward the end of his career, tired of having his films banned and his international travel restricted as his worldwide reputation grew, Kiarostami left Iran and made his last two films with international casts speaking English, French, and Japanese. Unlike some of his compatriots, he was never jailed by the country’s religious regime, largely because, at least until making the frankly critical Ten in 2002, he found indirect ways of presenting the realities of everyday life in Iran. Before Ten, the first of his feature films to be banned, Kiarostami was sometimes accused of ignoring the concerns of women. It was a choice he had made in part because stories involving child protagonists were easier to get past the censors in a country where women’s unveiled heads, never mind the conflicting ideas roiling inside their skulls, were considered too provocative to be shown onscreen. But late in his career he expressed regret about this omission and began creating female protagonists who were notably—and in the case of films like Certified Copy or Shirin, outstandingly—nuanced and complex.

When I heard about Kiarostami’s passing Monday, though, the first image that came to mind was that rolling can in Close-Up. The shot comes after what, in Kiarostami’s slow tempo, constitutes a suspenseful opening setup. A journalist hot on the trail of a scoop recounts to his unimpressed cabdriver the story he’s investigating: It seems that a grifter (Hossain Sabzian, playing himself; see above, re onion) has been posing as the famous director Mohsen Makmahlbaf. His impersonation has convinced a well-off Tehran family, who now treat him as their honored guest and even angle for roles in his upcoming movie, based on the false belief that this soft-spoken man is the creator of hit films like The Cyclist.

After the obliviously condescending journalist assures the ever less-engaged driver of the importance of this breaking scandal to his career, the would-be Oriana Fallaci hurries—armed police backup in tow—into a gated, wealthy-looking house. There, we are made to understand, the fake Makmahlbaf may be holding his former hosts hostage and is himself about to be captured and placed under arrest. At that apparently pivotal moment, the movie nonchalantly ceases to pay any mind, for quite some time, to whatever might or might not be happening behind those closed metal gates.

Instead the camera stays with the driver, who, left alone outside the closed compound, pulls his car into a nearby spot, gets out, and commences to wait. He stares up at a passing plane as it leaves a double contrail in the cloudless sky. On a raked-up pile of leaves by the curb, he notices a few cut roses still fresh enough to last a few days, and on a whim he gathers them up, discarding those too wilted to bother keeping. (If you haven’t done this at least once in your life, you’ve been wasting perfectly good roses.) As one stem dislodges a green tin can on the leaf pile, we—but who are “we”? Whose story is this? Who’s telling it? What exactly counts as a “story,” anyway?—are left to watch in confused, then anxious, then finally comical suspense as the nondescript green cylinder rattles its way toward the gutter, taking 35–40 seconds of otherwise silent screen time to come to a full stop. The can doesn’t release the audience’s tension by suddenly exploding, revealing itself to be a bomb planted by the identity thief. Nor does it represent the loneliness of the long-distance cabdriver, or foretell his or any other character’s tragic or comedic fate. It just rolls down a slight incline and stops when it gets to the curb, because … it’s a can.

The meaningless yet beautiful near-minute of attention paid to the trajectory of that tube of tin marked the moment when Kiarostami first ascended to my personal pantheon of directors: someone worth following down whatever zig-zagging path he might explore, in the company of whatever carful of arguing, philosophizing crackpots might pile in for the drive. (This is a man who enjoyed a chatty cinematic road trip, a narrative form that would recur in many of his best movies, including Ten, Certified Copy, A Taste of Cherry, and the three loosely connected films sometimes called the Koker trilogy after the village in and near which they take place: Where Is the Friend’s Home?, Life and Nothing More, and Through the Olive Trees.) Pay attention to everything, Kiarostami seems to remind the viewer. There’s no way to know in advance what’s going to end up mattering in this story, or any story, so just take a breath and keep paying attention. Now that his own biographical story has come to an end, one thing that seems certain is that Kiarostami’s movies mattered, and that people who care about film will be paying attention to them—moment by moment, breath by breath, rolling can by rolling can—for a long time.