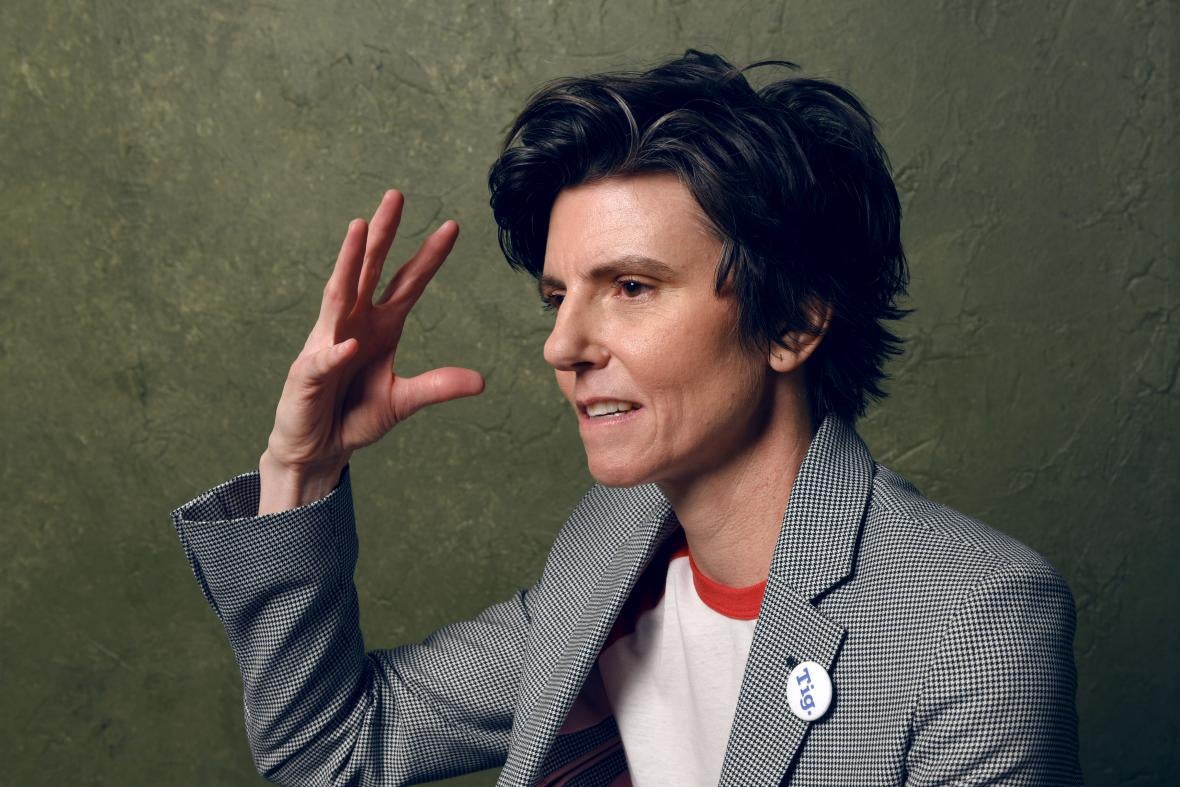

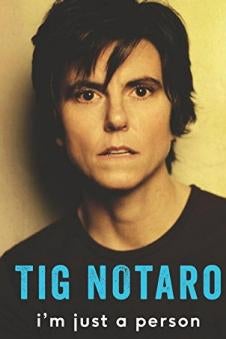

There’s a common wisdom that humor is the spoonful of sugar that makes the medicine go down. The idea is that people will listen to a deep or difficult reality—like Tig Notoro’s experience with cancer—if you wrap it in a joke. But Notaro’s new memoir, I’m Just a Person, shows that at its most powerful, humor is not a spoonful of sugar: It can be a bitter medicine itself. Notaro helps us understand the loneliness and alienation of her post-op experience, not by describing it in terms of something silly or clever and therefore more digestible. Instead Notaro describes her horrifying situation in terms of another more horrifying situation: “A nonstop stream of friends came by, but I was so jacked up on painkillers that my hospital room looked like a party going on around someone who had overdosed before the guests had arrived.” Tig Notaro’s comic lens turns up the focus on the absurd futility of her experience, making it more real and powerful, giving us an understanding that is just as comic as it is tragic.

I’m Just a Person is bookended with funny and insightful stories from Notaro’s childhood and discussions of her relationships with her loved ones. But the book’s core is her account of the year her life fell apart, and the way in which she and the people around her tried to process one tragedy after another:

During my wretched four months, I heard “God never gives you more than you can handle” way more than I could handle. But I can assure you that C-diff, the death of my mother, and breast cancer were each, individually, more than I could handle.

Despite this book’s subject matter, it does not feel heavy. Like Notaro’s stand-up, it feels effortless. It is Notaro’s brutal honesty and sugarless humor that give the book its lightness: a spoonful of medicine that makes itself go down. The book feels both so real and so digestible, leaving the reader with the faith that it is possible to go on living life even if life is “ultimately, more than [you] can handle.”

Notaro does for her readers what she says she did for her audience at her famous post-diagnosis show at Largo, in which she revealed that she had breast cancer: “I needed the audience to be empathetic but open, not overwhelmed and shut down by sorrow and pity.” She achieves this effect by doubling down on the reality of her tragedy, not by diminishing it or by focusing on an imaginary bright side. It is her humor—and her impeccable timing—that make her tragedy feel twice as real.

And there’s one scene in particular that captures exactly what makes the memoir overall so good—and her brand of comedy so bracing and singular. The chapter in which Tig Notaro sits by her unconscious mother’s deathbed builds up tension as we wait for her mother’s final breath, the most heartbreaking moment in the book:

Suddenly the gurgling stopped … all I could do was look at her intently. Then almost immediately after she breathed what was to be her last breath, that dark grey liquid seeped out of her mouth.

“I think my mother just died,” I told Kyle … I hung up with Kyle and walked out into the hall. There were a few nurses talking behind a kiosk. I stood right outside the door and said to all of them, “I think my mother just died.”

These passages are devasting, but there is a subtle comedy here too. The French philosopher Henri Bergson wrote that laughter is our response to seeing a living being acting mechanically; we laugh when people are unable to adapt to their environment and start acting like machines. Notaro is aware of this as she constructs these tragic passages, but she adds a new insight: These moments, when our usual veneer of adaptiveness and competence drops and we essentially malfunction, are the moments where we are most vulnerable and human. Reaction to extreme circumstances runs counter to expectation, often looking ridiculous and futile, like Notaro’s repeated, almost deadpan, “I think my mother just died.” It’s our ridiculous inability to handle the world that makes each of us just a person. Notaro’s memoir bears witness to this, and by doing so she makes the reality of her losses both very clear and often funny, without overwhelming us.

Ecco

Notaro’s deep commitment to reality is also the source of an unshakable optimism. It’s a rare feat to write so openly about a life like hers without a trace of bitterness and still seem genuine—especially for a comedian living in our insane and unjust world. “These days, I am very easily one of the happiest people you could cross paths with. I am surrounded by the most loving friends and family,” The difference between a sentence like this when it appears on a Hallmark card and when it appears in I’m Just a Person is that Notaro truly means it. Just as the memoir’s tragedy is bearable because it comes from an unembellished honesty, its optimism is bearable because it comes from that same place. Notaro’s is not the optimism of “God never gives you more than you can handle,” the optimism of denial. Her optimism is a quiet confidence that seems to spring forth naturally after having stared reality in the eyes and then giving it a wink. This is why she can give inspirational-poster-worthy advice and still be truly and meaningfully sincere: “[T]he best gift you can give anyone is a well-lived life of your own.”

The way she tells her story in I’m Just a Person shows that she’s taken her own advice: She tells us that the best way to talk to a deathly ill person is to open directly to their reality in the moment.

When I heard, “Wow, that sounds really hard,” or even an awkward “I don’t know what to say …” it was tremendously comforting. I felt as though someone was really talking to me and considering what was actually going on, and, most importantly, was willing to succumb to the moment instead of covering it up with a one-size-fits-all platitude.

Notaro sets an example by opening directly to her reality with a photorealistic lens that shows humans as glitchy machines who are always one loss away from short-circuiting in the funniest way and revealing their hearts.