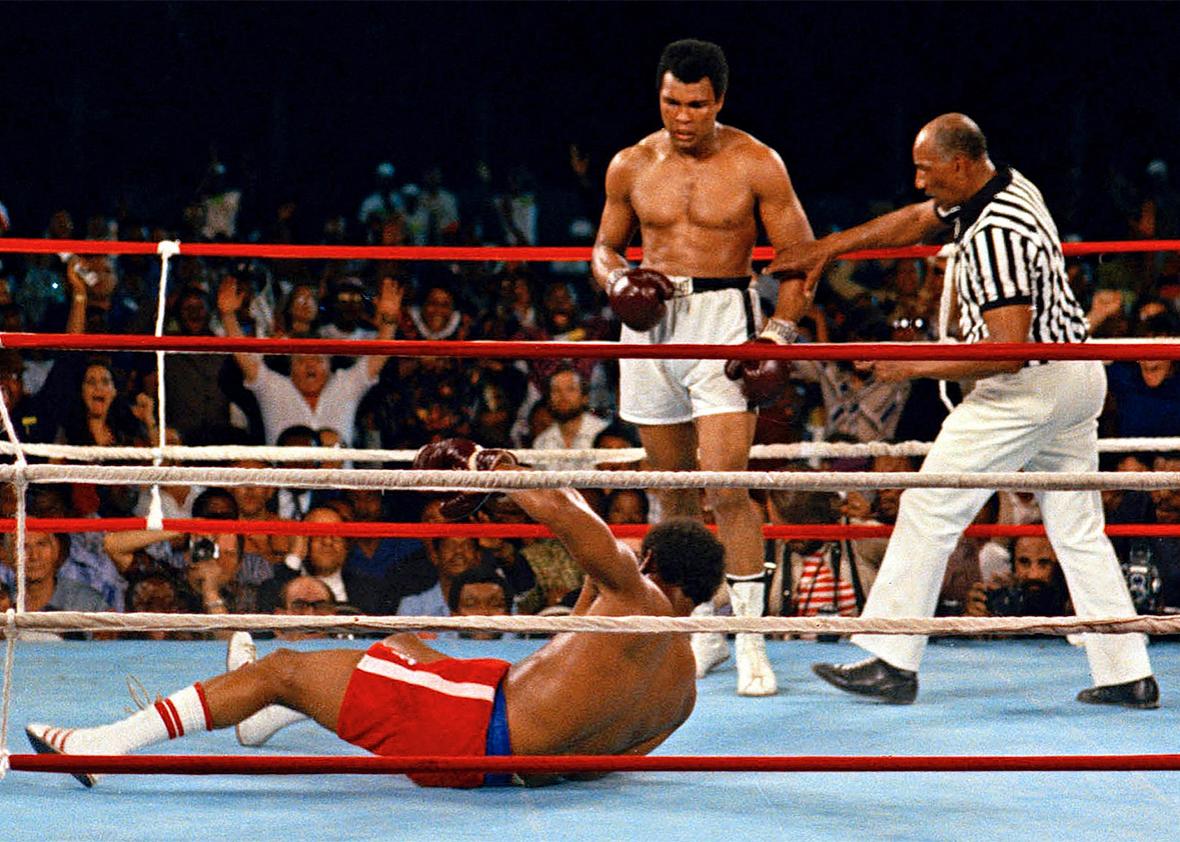

The death of boxing legend Muhammad Ali sent the world into mourning and fans looking for ways to remember him. Of the many attempts to capture Ali over the years, from a single sentence about his first fight to this weekend’s wall-to-wall coverage, Leon Gast’s 1996 film When We Were Kings perhaps came the closest to capturing the man in full. Rather than span Ali’s entire career, Gast tracked a single fight, the 1974 “Rumble in the Jungle,” in which Ali beat stiff odds to regain the heavyweight title from the much younger George Foreman. Ali’s strategic “rope-a-dope” victory made the bout legendary in its own time, but it wasn’t until 1996 that Gast, who was there, was able to assemble his film, simultaneously re-contextualizing the scope of Ali’s genius and introducing him to a new generation. Almost immediately upon its release, When We Were Kings earned a justified reputation as one of the greatest (sports documentaries) of all time, winning Gast and co-producer David Sonnenberg the Academy Award for Best Documentary. It’s not as easy to see as it should be—although MSNBC has been airing it this weekend—but if you’re missing Ali, seek it out. An hour and a half with the Greatest of All Time is worth the price of a DVD.

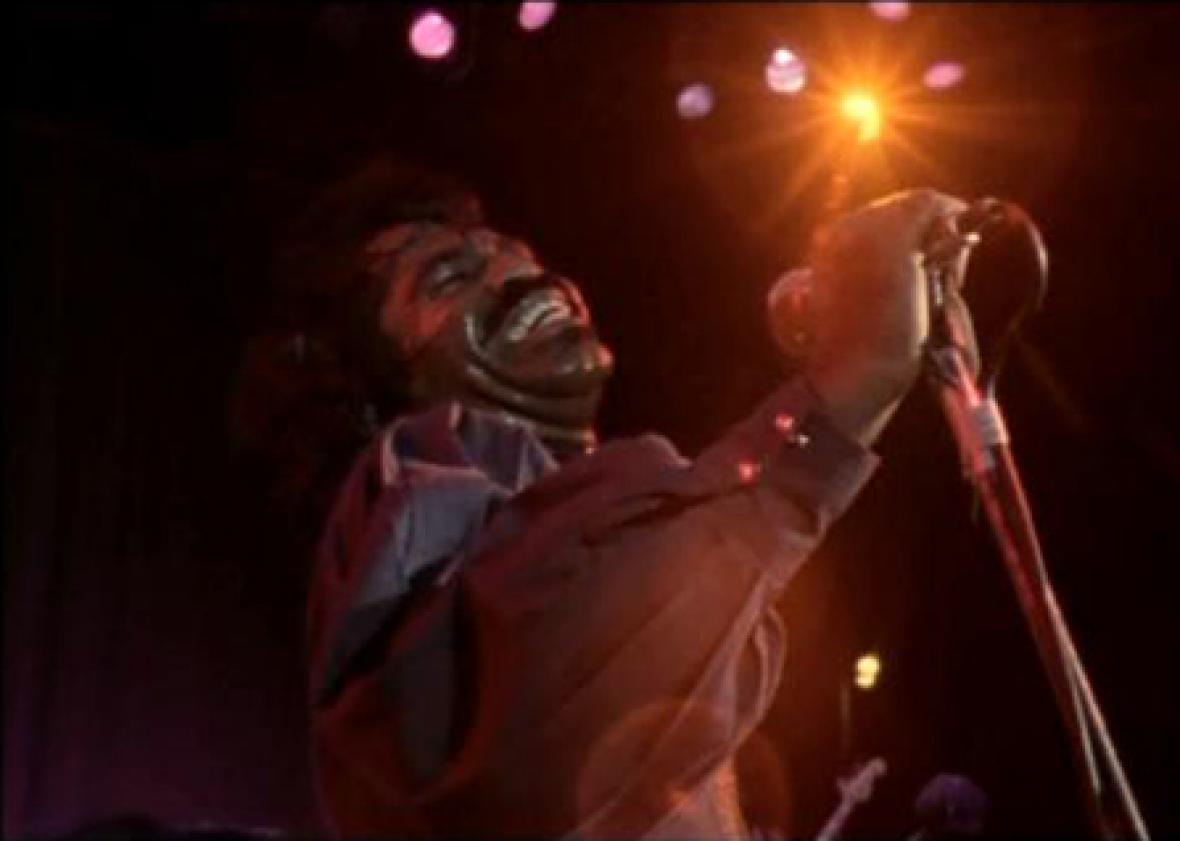

The film’s troubled 22-year path to the screen is its own epic, as Will Joyner reported for the New York Times back in 1997. When We Were Kings wasn’t even supposed to be about boxing—it was originally planned as a concert movie, something like Woodstock. In the early 1970s, promoter Don King managed to get Ali and then-heavyweight champion George Foreman to agree to fight the other if a $10 million purse could be raised. He found the money from Mobutu Sese Seko, the military dictator of Zaire, who was eager for the international legitimacy such an event would bring. King also got Mobutu to sponsor a music festival before the fight, Zaire ’74, which would feature African and black American artists. Documentarian Leon Gast convinced King he was the man to make the accompanying concert film. (King was hesitant to hire a white man but was impressed with his nerve; at the time, Gast was filming the not-very-cooperative Hells Angels.) Gast immediately started shooting footage of Ali training for the fight—the match was always going to be included but was not the focus of the film. And then the troubles began.

First, George Foreman got a cut over his eye, which delayed the fight six weeks. But the concert couldn’t be pushed back because the musicians had other engagements. The festival tickets had been priced for foreigners, not native Zairians—they went for as much as $24 in a country with a per-capita income of $100—and the foreigners all left. After the festival drew an embarrassingly small crowd on its opening night, Mobutu declared Zaire ’74 a free event. This was a disaster for Gast, whose film was supposed to be funded by proceeds from the concert. After putting up some of his own money to film the festival and events surrounding the fight, Gast discovered that the British production company ostensibly financing his film was, in fact, a Cayman Islands front run by the finance minister of Liberia. One legal battle later, Gast ended up with hours and hours of concert footage, hours and hours of training and interview footage of Ali and Foreman, no rights to any footage of the fight itself (it was shot exclusively for closed-circuit transmission to movie theaters), and no money to finish his movie.

Polygram

Gast’s lawyer, David Sonnenberg, put his own money into the film, allowing the filmmaker to put together a videotape rough cut—with the focus shifted to boxing—by the early 1990s. That was enough to spark the interest of director Taylor Hackford, who suggested adding additional context through talking-head interviews. Hackford filmed these himself, with his subjects including fight attendees Norman Mailer and George Plimpton, plus director Spike Lee. (Weirdly, the film has a title card proclaiming it “A Film by Leon Gast & Taylor Hackford” as well as one reading “Directed by Leon Gast.”) With those interviews added, Gast took the film to Sundance in January of 1996, where Polygram acquired it. After a one-week qualifying release in October of that year, it went wide during the 1997 awards season, spurred by its Academy Award nomination and eventual win for Best Documentary.

The two decades of catastrophes and delays may have been a blessing in disguise, because Gast couldn’t possibly have found a better time to release When We Were Kings. After dropping out of the public eye as his Parkinson’s worsened, Ali—a controversial figure during his career (at least, to white America)—had been canonized as a secular saint by the summer of 1996, when he lit the Olympic torch in Atlanta. George Foreman, too, was back in the public consciousness—the George Foreman Lean Mean Fat-Reducing Grilling Machine had debuted in 1994. It was a propitious time to have unseen footage of both men in their primes.

So what does When We Were Kings look like, 20 years later? Watching it for the first time since its theatrical release, what I saw was an extraordinary document but not the all-time-great film I remembered. There is no such thing as bad footage of Muhammad Ali, and he is amazing from his first appearance, which forcibly restores the politics that were so central to his character and had all but vanished in Atlanta:

Yeah, I’m in Africa, yeah, Africa’s my home—damn America and what America thinks! Yeah, I live in America, but Africa’s the home of the black man, and I was a slave 400 years ago, and I’m going back home to fight among my brothers.

As a film, When We Were Kings is a strange blend of documentary techniques, mixing Gimme Shelter–style vérité footage of the concert and fight with Hackford’s very 1990s talking heads. The 1970s footage is phenomenal, and not just because of Ali. Gast captured great performances from B.B. King, the Crusaders, the Spinners, and James Brown. Ali, of course, is also performing: Gast shows him turning every encounter with the camera into a virtuoso display of wit and charisma. And George Foreman commands the screen for the opposite reason: an almost willful lack of charm. It’s not really fair to cross-cut between anyone and Muhammad Ali, but Foreman does particularly badly:

In his most unfortunate misstep, Foreman arrives in Zaire with a German Shepard, the favorite breed of the Belgian police, which does nothing to endear him to the recently independent nation. And his wardrobe is mesmerizingly terrible:

Polygram

Hackford’s talking heads come in handy with the training and fight footage, especially for viewers like me who have limited boxing expertise. Mailer’s description of how Foreman cut off the ring—closing in on his opponent and making it impossible to dance away—is paired with footage of Foreman practicing this in training, in such a way that you can see how the technique works and why everyone was convinced Ali was doomed. Similarly, the explanations of both fighters’ tactics during the fight are excellent. But Mailer and Plimpton don’t confine themselves to tactics, and much of the rest of their commentary is, let’s say, not great. Mailer saying of Foreman, “He was negritude, he was this huge black force,” tells you much more about Mailer than it does Foreman. Nor is the film helped by Plimpton’s stories of féticheurs, which he describes like this:

They are witches, soothsayers, and in Western Africa almost everybody has one. They go to a witch doctor the way we would go to a dentist.

As University of Southern California professor Doe Mayer noted in the Los Angeles Times shortly after the film was released, Gast pairs Plimpton’s description of a “succubus” prophesied to drain Foreman of his powers with an extreme close-up of South African civil rights activist Miriam Makeba—a shot Gast reuses throughout the film. (The tastelessness of casting an important cultural and political figure as a succubus or witch doctor is compounded, as Ken McLeod pointed out, by the fact that she’s performing a song about the Pondo revolt.)

Polygram

For all the context the talking heads supposedly provide, there is an extraordinary amount of context-free “exotic Africa” b-roll: shoeless children dancing, women carrying bananas, and the like. This footage is usually intercut in ways that make the contrast between primitive and civilized very explicit, as when a shot of a woman carrying a bundle of firewood atop her head cuts to Americans loading suitcases into a truck.

Polygram

Also nearly context-free—as Mayer noted in the L.A. Times—are the appearances of Mobutu. Mailer talks about his sadism (and, in a classic Mailer move, says he was the kind of guy who made him feel bad for “the poor women who are associated with this fellow”). But no one notes the irony that Ali—who sacrificed his prime years as a boxer rather than participate in American imperialism abroad—was lending his prestige and legitimacy to a tyrant who rose to power in, at a minimum, a C.I.A.–created vacuum. It’s unrealistic to expect a film to address that vast context in so little time—O.J.: Made In America needed more than seven hours to handle Los Angeles, and Gast has 90 minutes for an entire country. But given how much time is spent on interminable stories from Mailer and Plimpton, portraying Mobutu as colorful and eccentric (or even as a murderer, but not as our murderer) does the subject a disservice. Ali never shied away from political complexity, but at times When We Were Kings does.

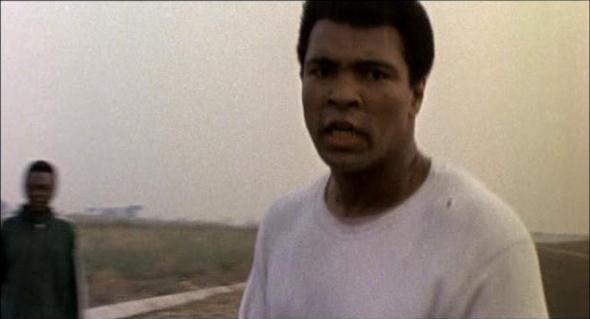

But whatever its flaws, there’s no better picture of what made Ali so great. In its small moments, the film lives and breathes. It’s alive in the amazing shot of Ali marveling at his plane’s all-black flight crew. It’s there when Don King offers a reporter a rapid-fire quote from As You Like It in lieu of an explanation. It’s there in every second of Foreman and Ali in the ring as Ali’s audacious strategy unfolds and pays off. But most of all, it’s there in footage Gast shot one morning of Ali running on a straight, deserted stretch of road, entourage in tow. It’s a cloudy day, and the sky is the same gray as Ali’s sweatshirt, but somehow he doesn’t dissolve into the background—he pops from the frame as though he’s backlit by his own charm and force of will. Leon Gast gives us Muhammad Ali, young and beautiful, throwing shadow punches at the camera with impossible speed. “No, I’m not there, I’m here,” he says, bobbing and weaving in and out of the frame, inviting us to follow. He’s dancing.

Polygram