Fully 51.1 percent of Nielsen-reporting homes watched the January 1977 finale of Roots. The miniseries was, at the time, the top-rated production ever seen on television. And many of the people watching reacted quite strongly to what they saw. “Roots prompted the first ‘national conversation on race,’ ” historian Matt Delmont writes, “with all the hope, ambiguity, and futility this Clinton-era phrase evokes.”

Delmont’s book Making Roots: A Nation Captivated is a history of the creation and reception of the original Roots book and miniseries. In the course of his research, Delmont collected a group of letters written to newspapers after the miniseries was aired, which you can read on a web page meant to accompany his book.

As the rebooted Roots miniseries airs on A&E, History, and Lifetime this week, I spoke with him about a few of those letters, to try to get a sense of how Americans in 1977 responded toRoots.

Mr. Haley, I did not watch Roots because I knew I did not want to live through slavery again. I don’t think it helps the Negro American’s image, and we are Americans now after four or five generations. I’m sure it did you a lot of good to write the book. The people that read a big book probably could handle it, but a big spread on television with a lot of already frustrated people watching was very bad for race relations.

—Ganell Taylor, Chicago Defender, Feb. 17, 1977

Delmont: This is difficult material to watch, and it’s especially difficult material for African-Americans to watch if you know you had an ancestor several generations back go through something like this. The producers didn’t give a lot of thought to that. They wanted to make this a really visceral production, but they didn’t give a lot of thought to “What does it actually meant to ask people to watch these historical events be replicated in that way?”

It’s the first time the Middle Passage was represented on TV, and it’s the first time slavery was represented with that kind of brutality on television. I think one of the big differences, jumping forward to today, is that there’s just so much more violence and gruesomeness on contemporary TV—think about Game of Thrones—we’re almost desensitized to it in some way. At the time when Roots was on, you just didn’t see this kind of physical violence, especially physical violence that was historically relevant. That was just something that many viewers found almost too difficult to watch. There were people describing it making them physically sick. They had to turn off the TV and turn away.

After viewing the movie and reading the novel, I shall never be the same. It gave me a sense of pride and dignity. I cried with the characters, I laughed with them, I felt their lashes, understood their agony. The outstanding thing about Roots is that it was written by a black man, about a black man and his courage and determination to hold onto his true identity. Nothing I have read since the Bible has had such an impact on my life.

—Janice Turner, Los Angeles Sentinel, March 10, 1977

Delmont: I think one thing people forget about the original Roots is the way it created full black characters. Because it was so long, and because it created this multi-generational family story, it gave viewers a chance to see characters express a range of emotions. So they’re happy, they’re sad, they’re in pain, they’re hopeful about what might come next, they’re fearful about what might come next … It just gave so many characters the opportunity to act, to express a full range of human emotions, that you just didn’t see black actors get a chance to do on network TV in this era.

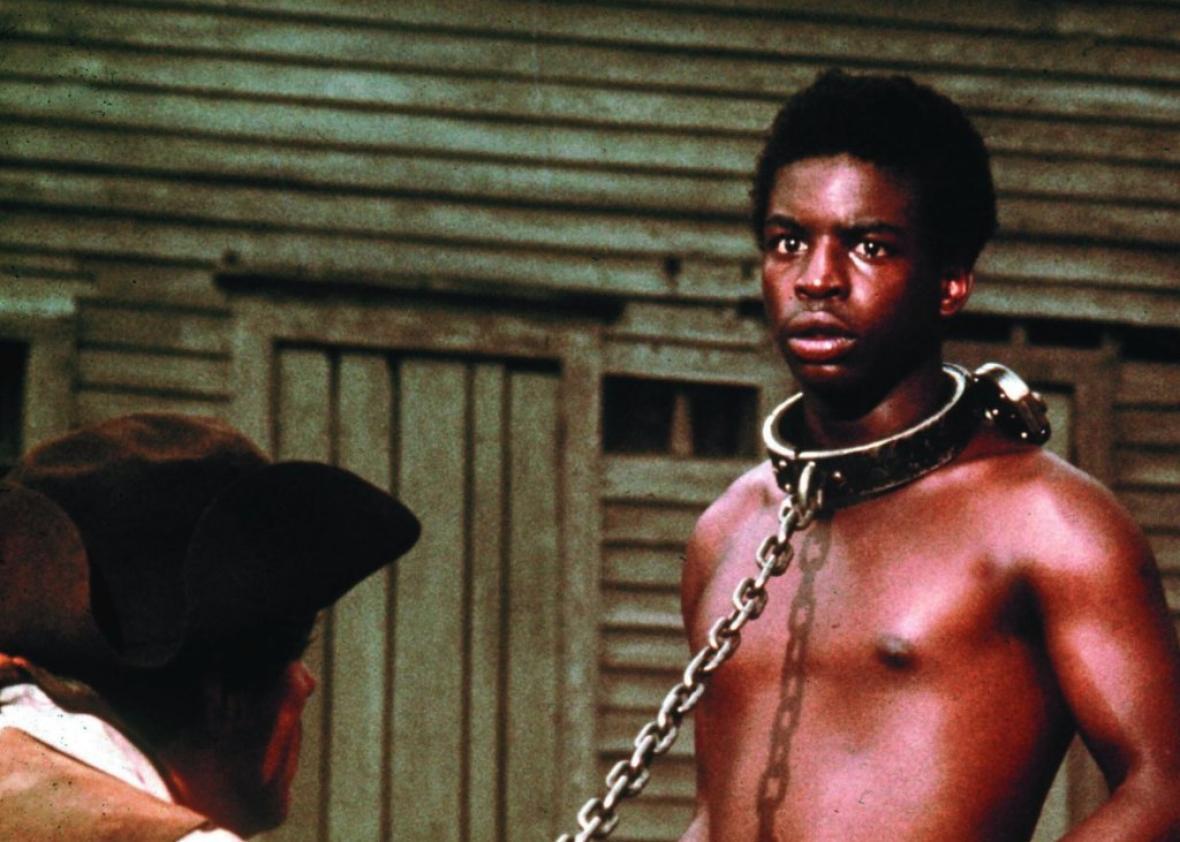

The whipping scene, where LeVar Burton’s character Kunta Kinte is whipped until he accepts his slave name of Toby … that’s one of the ones people tend to remember, but if you go back and watch the original series it’s not actually representative of what goes on in the series. There’s actually a lot of talking, conversations in the slave quarters, conversations between enslaved characters and the masters … trying to navigate basically surviving this institution of slavery. The physical brutality was certainly part of it, but also it was about trying to live as an enslaved person.

I have had first hand information from scores of reliable persons who lived during that period and I am convinced that most of those grisly tales were plain lies. Personally, I feel no guilt in the matter … Most of these owners were kind and compassionate toward the Negroes.

—Mrs. C.F. Stockburger, Austin American-Statesman, Feb. 20, 1977

Delmont: One of the things that Roots tried to challenge were mythic histories about what slavery was about. And I think those histories came from two places. I think one, as this person’s alluding to, was family stories and community stories. So, in the same way that Haley was getting his family story passed down from his African-American ancestors, a number of letter writers, who wrote letters directly to Haley or to the TV executives, talked about how they were the descendants of slaveholders, but their family’s stories had assured them that their slaveholding ancestors were kind to their slaves, and that, in fact, their slaves loved the slaveholding ancestors.

Those are stories that have lot of power, and I can just picture them being passed down generation to generation to explain who your great-great-grandparents were. You need some way to make sense of that, that maybe there were bad slaveholders, but certainly your ancestors were not among them, your ancestors were on the good side of that. I think Roots helped to push against that, because it was a generational family narrative. It helped to push against this idea that plantation families were happy families. To make the point that there was no “happy family” if one family was owned.

The other mythic history that Roots was up against was something like Gone With the Wind. Before Roots came out in 1977, Gone With the Wind was actually the most-watched TV program of all time, when NBC aired it over two nights in 1976. So it’s kind of crazy to think about: At one point Gone With the Wind and Roots held the No. 1 and 2 places as the most-watched TV series of all time.

I am a 21-year-old white man. The program, Roots, which Channel 9 telecast, has prompted me to write this letter … I am ashamed to be white. To think my ancestors could possibly be so animalistic to the ancestors of [black] people. Isn’t it about time we, as whites, did something to repay the great torture, humiliation and embarrassment our forefathers caused the blacks? I, myself, don’t know what to do to help repay this debt, but I am willing to do any reasonable thing suggested. At this point, I wish I could just cut this white skin off my body and replace it with black because my heart, soul and feelings are as a black’s. I have shed many a tear over this move and will probably shed more. I appeal to the people of Denver and Colorado as Christians to be the first to begin helping me repay this debt. For God’s sake, let’s do something.

—Paul Boston, Denver Post, Feb. 10, 1977

Delmont: There were tons of letters that expressed white guilt. I think this is the peak of the form of the white-guilt letter. I can almost picture this young man writing, just having the ideas come to him as he’s writing the letter. The reference to “We need to help pay this debt” almost gestures toward reparations in a way you don’t always see with these expressions of white guilt.

One of the things that made Roots powerful in the 1970s was that African-American history was very new to a lot of people. Of course there had been generations of African-American historians doing this work, and you start to see more of it in the academy in the 1960s and 1970s. But it hasn’t yet trickled down to junior high or high school textbooks, in 1977, and it hasn’t yet gotten into the popular consciousness. So if you’re just an average American in the 1970s, you’re unlikely to know a great deal about African-American history.

I think this letter is indicative of that. It was a TV program that struck him, that he needed to be concerned about what his ancestors did … It’s in some ways shocking that it would take a TV series to force that consciousness, but it speaks to the way a TV series could be a very powerful form of popular history.

There’s a follow-up response letter to Paul Boston’s, in the Denver Post, another white letter writer, who goes through and lists a series of great white inventions, things that white people have given to America. So Roots was the occasion for an expression of white guilt but also for white people saying basically “White pride!”

I watched Roots and would like to put things in proper perspective for those who are ashamed of being white after viewing this show. The superlative accomplishments, made in every known field by the present generation of the white race, are beyond my ability to describe. If you are alive you are experiencing a considerable quantity of them each and every day … And some people have the audacity to be ashamed of being white. It’s almost sacrilegious.

—Norbert Faulstich, Denver Post, March 3, 1977

Delmont: The other thing that strikes me is that there’s a big difference between the book and the TV series. For the TV series they added in more white characters, because they were concerned that white viewers won’t watch if they don’t have famous white actors in the series. They have Ed Asner show up, he’s in there after 10 minutes as the slave [ship] captain, as well as a number of other very popular white TV actors of the time … I think it prompts more of a sense of white guilt than the book did. For the book, the white characters are almost irrelevant. You’re 250 pages into the book before there’s a white character with a proper name. Before that they’re all just called toubab. But for the TV series they had to make the white characters more compelling.

If there had been no Drum and Mandingo, there would have been no Roots. As always, in search of the dollar, television had an uncanny ability to cash in on the latest fad, and these days that appears to be slavery.

—Cliff Pugh, Baltimore Evening Sun, Feb. 17, 1977

Delmont: Mandingo [1975] and Drum [1976] are blaxploitation, almost sexploitation movies. They’re playing up these interracial master-slave romances. They’re set in the era of slavery, but they’re definitely interested in titillating viewers with this history, with the power dynamics of slavery and lust across racial lines … There are interesting things going on in both films, showing the kind of sexual violence and the kind of sexual relations that go on during slavery. I don’t know if these are the best places to try to understand this, but they’re interesting.

One of the most famous slams of Roots was a critic in Time magazine who called it “middlebrow Mandingo.” Which I think, when you link Roots to that tradition, that’s really meant to undercut it. To [say that its creators were using] Roots only to try to titillate viewers, with scenes of the whippings or with the implied rapes.

About the reference to “cash in on this fad”: I think appearances of slavery in popular media do tend to go in cycles. So you saw a cycle of movies in the 1970s that were talking about slavery, and you saw a few in the 1990s, and now we’re seeing a host of TV series and films … and most of the recent ones have been very good.

But Haley actually started the book in the early 1960s, and planned to finish it in the mid-1960s. Columbia Pictures had the first film rights to it in the late 1960s. So it’s coincidental that Roots came out after Drum and Mandingo. It wasn’t like Drum and Mandingo did well and then they said “Let’s get Roots on TV.”

Roots is the new Uncle Tom’s Cabin. The thing people in the South held against that book was not its depictions of cruelty—everyone knew about that anyway—but rather the fact that it depicted Negroes as having human intelligence and human feelings just like themselves.

—Roe Fowler, Fresno Bee, Feb. 7, 1977

Delmont: I think this is a really smart letter. Because I think what’s going on in Roots, and one of the things people were finding powerful about it, was the three-dimensional black characters. It shows you African-American characters in their own spaces being sly about their humor, sort of knowing about what’s going on in the big house and trying to use that knowledge in ways that are going to help them. It shows them caring for their families and having hopes and desires and dreams about what’s going to come next for them and for their descendants.

And that has a lot to do with the genre it was in. The reason it makes sense to connect it with Uncle Tom’s Cabin is that the original Roots was very much a melodrama. It had a heightened sense of who was good and who was evil, but it gave viewers a chance to hear enslaved people talking and reasoning and expressing themselves, in ways you just don’t see in popular media.

I like the new version a lot, but I think they’ve gone more in an action-thriller direction. The characters are still three-dimensional, but the way you’re asked to care about them is by hoping they’re going to fight back or win a battle, as opposed to appreciating their wit or their sentiment like you did in the old version.

The last thing about Uncle Tom’s Cabin is the kind of cultural influence it had. Uncle Tom’s Cabin was a phenomenon in its era; it was performed everywhere, on stages, in minstrel halls, and got re-produced in different cities and towns. That kind of mass-cultural moment is really difficult to achieve in the present. But Roots was able to do it in the 1970s, in the same way Uncle Tom’s Cabin was able to do it in the 19th century.

This conversation has been edited and condensed for clarity.