The titular subject of Keanu, the just-released film debut by comedy duo Key and Peele, is an adorable kitten, battled over by warring drug gangs. But arguably, the movie’s spirit animal—and for music geeks, perhaps the best reason to see this charming, uneven film—is a British singer who peaked on the charts three decades ago.

That would be stubbled, leather-jacketed, ass-shaking ’80s megastar George Michael. His music not only appears throughout the film, but Michael himself even appears in vintage music-video form during a drug-fueled dream sequence. Michael is the favorite musician of Clarence, the nebbish-posing-as-thug played in the movie by Keegan-Michael Key. If you’ve only seen the Keanu movie trailer, which prominently features George Michael’s music at the beginning and end, you probably think you know the role Michael plays in the story—as a signifier of the Key character’s suburban squareness. When Clarence is alone in his minivan, he sings along lustily to Michael’s “Faith.” And when he later, improbably, finds himself trying to impress a posse of drug gangbangers in said minivan, he is (apparently) busted when the squad finds Michael’s music on Clarence’s iPhone. “Awwwww—this my shit right here,” the terminally unhip Clarence declares to the gang, unconvincingly, as “Freedom ’90” plays.

But this interpretation of George Michael is complicated by both the film itself and by Michael’s own history as a music star. The actual joke of the movie is that the badasses in the drug ring come to love Michael’s music through Clarence, who turns them on to several of the singer’s hits and strongly implies he is black. (One character even asks Clarence if Michael deserves an N-word sobriquet.)

And here’s the thing: George Michael was a serious, no-joke, R&B-chart-topping megastar with black audiences at his late-1980s peak. He even topped Billboard charts with “Black” in their titles. Like the duo behind Keanu, Michael was a first-class code-switcher—a perfect musical touchstone for Key and Peele.

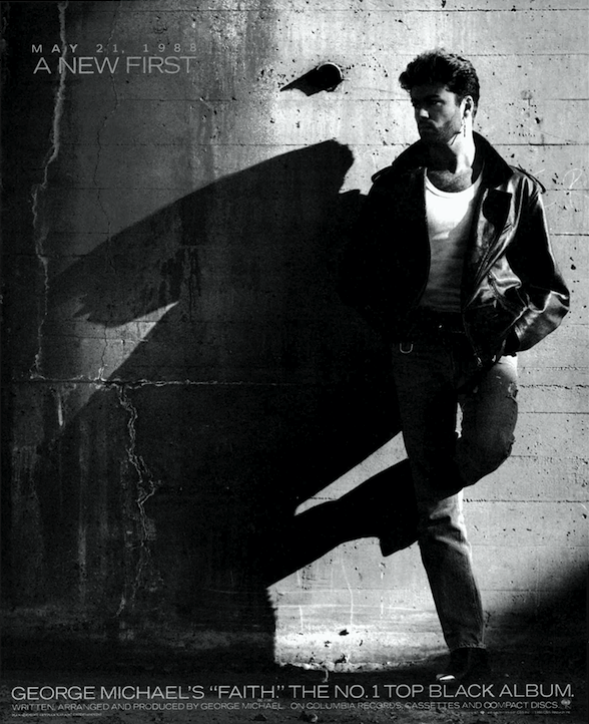

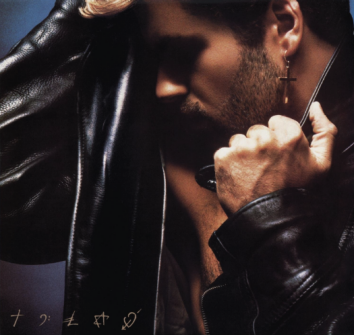

Columbia Records

In the five seasons their satirical television show blazed a trail on Comedy Central, Keegan-Michael Key and Jordan Peele played over and over with this idea of code-switching—the way everyone from substitute teachers to Liam Neeson(s)–loving security guards to our biracial President would defy ethnicity-based expectations of their tastes, their modes of presentation, or their perceptions of the world. That fascination carries over to the duo’s film debut. Start to finish, Keanu’s fish-out-of-water plot is a meditation on the modern idea of blackness: dropping two harmless, feckless, cat-loving geeks into a macho, gangsta-style milieu and seeing how long they can mask their blerd core.

So of course one of them loves George Michael. It has never been cutting-edge or especially cool to love Michael’s music—certainly not in 1984, when Wham!, the duo Michael formed with talent-challenged childhood buddy Andrew Ridgeley, first topped the Billboard Hot 100 with their perky anthem “Wake Me Up Before You Go-Go.” That song broke them in America and made the pearly-smiling, sloganeering Wham! look like the one of whitest acts on the hit parade of an otherwise crossover-fueled year for pop.

But that U.S. breakthrough hit rather belied George Michael’s preternatural interest in black music, evidenced as early as Wham!’s 1982 breakthrough in the U.K. The duo’s first two smashes on the British charts, “Young Guns (Go for It)” (U.K. No. 3, 1982) and “Wham! Rap (Enjoy What You Do?)” (U.K. No. 8, 1983), both made heavy use of Michael rapping—and not just on the bridge of the songs, à la other early whites-rapping classics like Blondie’s “Rapture.” To be sure, no one in B-boy culture was popping and locking to these teenybopper Wham! hits in 1982 or 1983 (the way they were to, say, Malcolm McLaren’s improbably inner-city-hip “Buffalo Gals”). But at a time when leading British musicians were heavy into New Romantic preening and sophisti-pop crooning, George Michael was spitting over a beat, barely three years after “Rapper’s Delight.”

The 1984–85 follow-up to “Go-Go” was a song billed as a Michael solo single around the world but tagged as “Wham! featuring George Michael” on the Billboard charts: “Careless Whisper,” one of the most remarkable left turns for a new pop act in the ’80s. A sax-drenched tearjerker, belted with gusto by Michael, the never-gonna-dance-again “Whisper” is, structurally and vocally, basically a soul ballad—albeit one with its other toes dipped in Sade-style lounge-pop and teen-pinup smolder-pop. The song was a pop smash, topping the Hot 100 for three weeks and later named Billboard’s top pop single of 1985. But it also reached No. 8 on Billboard’s R&B chart—remember, this was just months after the white-bread “Go-Go,” which didn’t go anywhere near that chart. A couple of months after “Whisper,” Wham! topped the pop chart again with their R&B-flavored midtempo jam “Everything She Wants,” which also reached No. 12 on the R&B chart.

A word about that chart: From mid-1982 to late 1990, Billboard called it Hot Black Singles. The methodology and fundamental aim of the chart was to track the song purchases and radio airplay of fans of black music. As critic and then-director of the chart Nelson George noted in 1982 when the name change to “Black” was made, the chart was overwhelmingly dominated by musicians and singers of color. In fact, in the eight years the chart was called Hot Black Singles, only four white artists topped it: Michael Jackson duet partner Paul McCartney, “Ivory Queen of Soul” Teena Marie, British soul vocalist Lisa Stansfield, and George Michael. And of the four, only George also topped the corresponding album chart, Top Black Albums.

Columbia Records

Michael pulled off the double-topper with Faith, his 1987 solo debut, which made him the biggest solo-male music star of the late ’80s (topping even Michael Jackson, whose ’87 album Bad sold millions fewer copies in the U.S. than Faith). He’d already had a good year at black radio, having reached the Hot Black Singles top five in the spring with the Aretha Franklin duet “I Knew You Were Waiting (for Me)” (No. 1 pop, No. 5 R&B, 1987). So it didn’t take black audiences long to determine that Faith was essentially an R&B album in pop-star drag. Weeks before the album dropped, Michael’s label worked the urban-tinged single “Hard Day” exclusively to black radio, eventually getting the song to No. 21 on Hot Black Singles; it never made the Hot 100. Faith debuted on Top Black Albums—a chart then tabulated exclusively from sales at black-owned-and-oriented record stores—in early December 1987, just a couple of weeks after it debuted on the Top Pop Albums chart. And it continued to spin off black radio hits—selectively: The rockabilly single “Faith,” for example, an enormous pop hit, didn’t chart R&B at all. But the gospel-tinged follow-up “Father Figure” (No. 1 pop, No. 6 R&B, 1988) returned Michael to the R&B Top 10.

Finally, in spring 1988, the coup de grâce: Faith reached No. 1 on Top Black Albums and stayed there for more than a month. And in mid-June, Michael scored his biggest crossover single ever when “One More Try”—his epic, churchy power ballad, a more mature spiritual successor to “Careless Whisper”—reached the top of both the Hot 100 and the R&B chart. Faith was still commanding the corresponding albums list; for that one week, if you opened Billboard magazine and flipped to the Top Black Albums page or the Hot Black Singles, you would find both charts topped by George Michael.

This warm embrace by the black audience made Michael a unique figure in ’80s crossover. On an organic, song-by-song basis, the R&B marketplace determined when Michael had switched the code to their liking. Michael Jackson and Prince are, rightly, cited as the top crossover stars of the period—black barrier-breakers on the pop charts who commanded both the Hot 100 and Black Singles lists repeatedly. But among white stars, George Michael basically stood alone. Unlike Teena Marie, a regular R&B chart presence who scored few Hot 100 hits, Michael was a full pop megastar to white America. And on the R&B chart, he scored more Top 10 hits than periodic crossover stars Hall and Oates, Phil Collins, and Madonna combined. (His status as a then-closeted gay man also made Michael an important crossover figure, not only across genres but also in dance music circles, where he enjoyed consistent popularity.) By the ’90s, Michael’s R&B chart presence began to wane, a couple of years ahead of his wilting on the Hot 100—I will never understand why the heavily soul-inspired “Freedom ’90,” a Top 10 pop hit, didn’t make the R&B chart, for example. But by then Michael was firmly implanted in the happy memories of fans of ’80s R&B and pop.

Fans like, say, Keegan-Michael Key, who as a biracial Michigan native might as well be the archetypal George Michael fan. Born in 1971, Key’s late-’80s high school years were soundtracked by George Michael’s music. When asked by USA Today how songs like “Faith” and “Father Figure” came to be featured so prominently in Keanu, Key became instantly wistful: “All I did for the George Michael dance sequence was, just, summon all of my … everything I ever did at every school dance from 1985 to 1990. I just wanted to channel all of that stuff—I went back there, and then, it just came out of my body. I had no idea … The lizard brain just took over.”

As for George Michael himself, now 52, he signed off on all the uses of his music in Keanu and—having determined that Key and Peele’s script did not make him the butt of a joke—is reportedly delighted by the movie’s lionizing of his past. Michael’s longtime manager reports plans to remarket Michael’s music sometime in 2016. I doubt it’ll return Michael to the top of the pops, but a boy can dream. In this year of profound sadness for music fans—with the charts repeatedly dominated by artists who had to die to remind us of their genius—how nice to see a fondly remembered fiftysomething musician returning to the pop conversation while still around to enjoy the comeback. Even if he is upstaged by a kitten.