In part thanks to this Q&A between Slate’s Rebecca Onion and Rutgers professor Lyra Monteiro, a conversation is finally brewing about how Hamilton, the brilliant musical phenomenon, approaches history, the factual record, and its real-life subjects. If, like me, you work in theater and spend a lot of time procrastinating on social media, you’ve probably seen many of your friends ranting about small-minded academic quislings fact-checking every minute of the show from their ivory towers. Recently, after the New York Times published a piece in which multiple historians discussed Hamilton’s storytelling choices and racial politics, Vox’s Aja Romano dismissed the entire discussion as “concern trolling,” because Hamilton is, in its essence, a work of “fanfic, functioning in precisely the way that most fanfics do: It reclaims the canon for the fan.” Romano’s identifying of the many fan-fiction tropes that pop up in Hamilton is illuminating, but her dismissal of historians and their point of view is off-base. Fans of Hamilton seem to want this conversation to go away, but it’s exactly the conversation we should be having about this musical, of all musicals.

Meanwhile, John McWhorter, writing in the Daily Beast, misunderstands what is clearly an examination of Hamilton’s point of view and mischaracterizes the entire debate as baseless accusations of racism hurled by “professional Cassandras.” Given that one of those “professional Cassandras,” Annette Gordon-Reed, is largely responsible for changing the national conversation around Thomas Jefferson, leading directly to how he is characterized in the musical, maybe we should at least hear them out.

Were the historians in question simply fact-checking the work, I might share the frustrations with the exercise. As I’ve written before, obsessively demanding that fictional works take place in our world diminishes art, and can also, as Neil deGrasse Tyson’s Twitter feed amply demonstrates again and again, just make you a blowhard. But that’s not what these critics are doing. They’re doing what good historians specialize in: probing issues of meaning and the politics of the work. This is why it’s especially disappointing that historian Ron Chernow, who wrote the biography of Hamilton on which the musical is based and receives regular royalties from the production, characterized the debate as “sad” because Hamilton “is the best advertisement for racial diversity in Broadway history,” a statement that would come as a shock to George C. Wolfe, or the ghosts of George Gershwin, Orson Welles, or August Wilson.

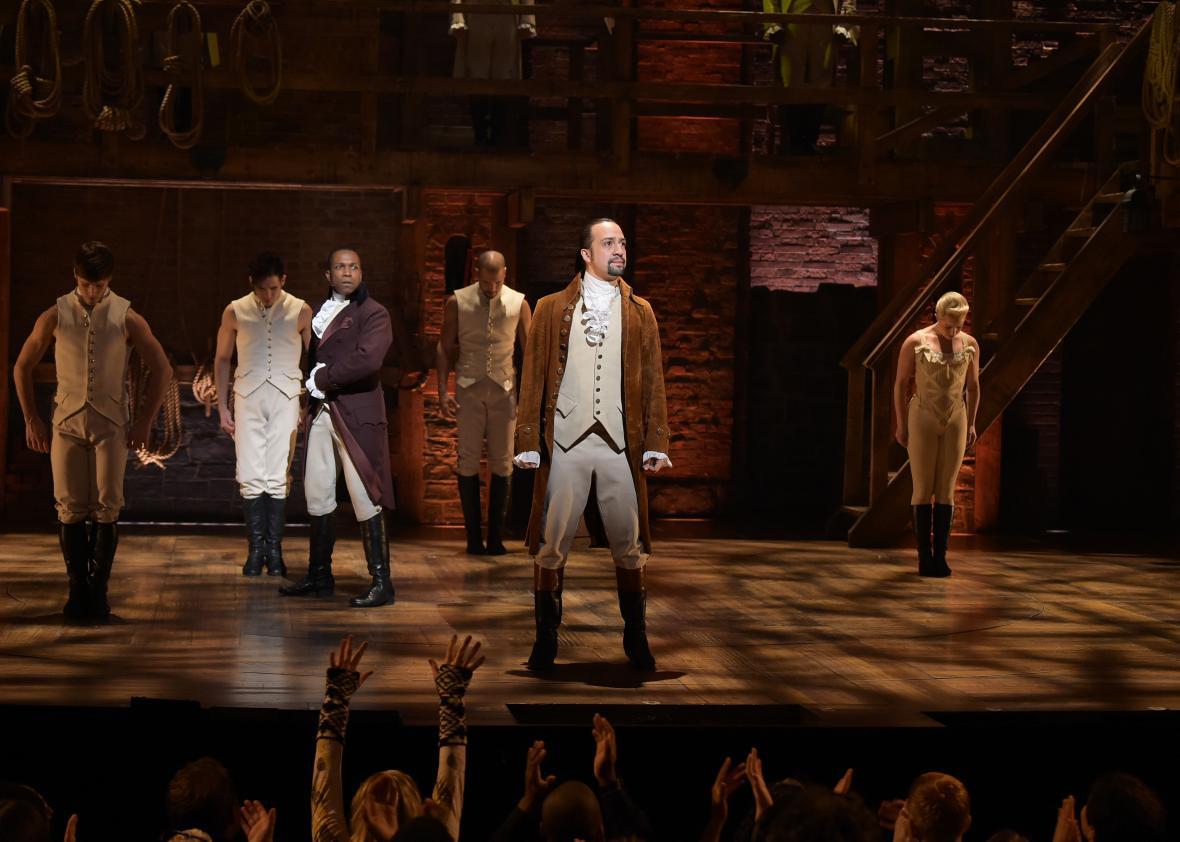

Fans of Hamilton often seem motivated by an earnest desire to protect the show. But the show doesn’t need protecting. Hamilton is now unstoppable. It has tens of millions of dollars in advance sales sitting in an escrow account, tickets go for more than $1,000 on the resale market, it will sweep the Tonys, and likely win a Pulitzer Prize. The original cast recording is a best-seller. First Lady Michelle Obama called it “the best piece of art in any form that I have ever seen in my life.” Last week, Grand Central Publishing released the “Hamiltome,” Hamilton: The Revolution, co-written by the musical’s creator-star Lin-Manuel Miranda and former Public Theater staffer Jeremy McCarter.

Hamilton’s defenders might not realize this, but what they’re actually trying to protect Hamilton against is being taken seriously. Regardless of whether each historian quoted in various interviews is right—how could they be, when they disagree with each other?—it’s a good thing that we’re having this debate. A great work of art demands robust, free-wheeling, critical engagement. For the most part, we’ve instead relied on Hamilton’s creators, its die-hard fans, and its PR team to define the show. But if Hamilton is as great as we think it is (and I do think it’s a generationally great work of art) there should be an ongoing critical conversation about it, one that crosses disciplines, and stretches for years, or decades, or perhaps—as has happened with Shakespeare, the Greeks, Ibsen, and others—centuries.

Besides, Hamilton isn’t exactly a work of fiction, or of fan fiction. It’s fan nonfiction, occupying that odd based-on-a-true-story space that we as a culture still don’t really know what to do with. Obviously, works of art have the right to take liberties with the facts, but that doesn’t mean discussing those liberties is off the table, particularly with Hamilton, which is deeply and explicitly invested in questions of historical storytelling. It returns to this theme again and again. Hamilton is obsessed with how history will view him, as, ultimately, is Aaron Burr. At one point Hamilton—that is, the show’s writer, Miranda—breaks the fourth wall to tell the audience that a particularly juicy allegation is true. Gaps in the historical record form the basis of “The Room Where It Happens,” one of the show’s strongest songs, and “Burn,” one of its weakest. The show’s final song features the cast repeating its title over and over. That title—“Who Lives, Who Dies, Who Tells Your Story,”—was also Hamilton’s marketing tagline when it bowed at the Public Theater. Ignoring how the show approaches history and the choices that create this approach and what those choices mean would be like arguing that no one should talk about the politics of Angels in America or the ways in which The Force Awakens is in conversation with A New Hope.

What’s remarkable about the criticism of Hamilton—and basically unique in the history of American theater—is that even the most vocal critics of Hamilton share with its fans a love for the show. Pulitzer Prize–winning historian Annette Gordon-Reed, who wrote that “[t]he genius of black music and black performance styles is used [by Hamilton] to sell a picture of the founding era that has been largely rejected in history books,” also told the Times she listens to the soundtrack every day. Loving a work of art involves advocacy and championship, but it also demands of us that we question it, interrogate it, work to see it for what it is honestly and with clear eyes. Dismissing this line of inquiry entirely and demanding that Hamilton be uncritically celebrated is against what Hamilton itself is doing and what it asks of all of us. Hamilton is a great play. It’s time to treat it like one.