When Marvel Comics announced last September that Ta-Nehisi Coates would be writing a series about the superhero Black Panther, fans were thrilled. Vulture called it “the most significant superhero-comics news of the year,” while Claire Landsbaum enthused in Slate that Coates was “indisputably a great choice to pen” the character’s adventures. Coates seemed like a natural fit to carry on the legacy of the first major black superhero. As a well-credentialed comics fan, he was clearly prepared to handle a character who’d been a player in the Marvel universe for almost fifty years.

That enthusiasm only built in the months leading up to the actual release of the project, with articles in the New York Times, the Guardian, and other publications expanding the comic’s reach beyond the fans who sustain Marvel’s print publications. Now that it’s finally here, however, it’s hard to know what to make of the series’ debut issue, which published on Wednesday. Coates, who has never written a comic before, still seems to be finding his voice in the medium. Though the art by penciler Brian Stelfreeze is crisp and precise, entire pages are sometimes hard to follow—the action choppy and characters’ backstories fuzzy.

Despite that, Coates’ comfort with Marvel’s traditions is evident in virtually every panel. In interviews and on Twitter, he’s shown that he approached the assignment like a scholar, delving deep into the Panther’s history, and his evident erudition only underscores the book’s occasional befuddlements. The first of eleven planned installments, it reads sluggishly despite its frantic pace, at once burdened by and benefiting from the narrative histories it draws on.

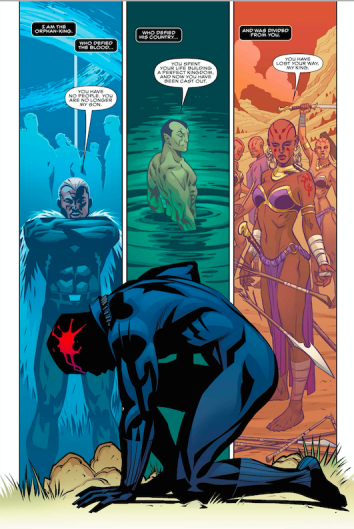

The issue begins in a jagged rush: We meet our costumed hero—who is also known as T’Challa—in the middle of an uprising in Wakanda, the secret African nation that he rules. “I came here to praise the heart of my country, the vibranium miners of the Great Mound. For I am their king and I love them as the father loves the child,” he thinks as he studies the chaos. We never learn, not in these pages, anyway, exactly how that chaos began. Indeed, we never so much as see the blow that brings him to his hands and knees on the book’s opening page.

Marvel

It’s a strange, abrupt way to begin a heroic epic, our hero on all fours, his head bloodied. And yet it’s also not entirely exceptional within the history of superhero comics. We delight in lowering heroes to our level, if only so that we might ascend with them when they inevitably rise again. Consider the Black Panther’s own first appearance in 1966, which featured him humbling the Fantastic Four (who are dicks that deserve everything bad coming to them) in much the same manner.

The Verge’s Kwame Opam finds something unusually powerful in this moment of powerlessness, writing, “As the symbol of Wakanda itself, the Black Panther embodies the country’s power and heritage.” Seeing this ostensibly well-meaning ruler brought down, it’s tempting to identify a political critique in the making, perhaps a critique that would echo Coates’ own searing indictment of America in Between the World and Me: “One cannot at once claim to be superhuman and then plead mortal error.”

In other words, this image suggests that those in power have failed, creating a vacuum that others must fill—a thesis that would help explain the issue’s baffling shifts of perspective, and its too-brief focus on T’Challa himself. And yet Coates has been the first to claim that he’s not looking to make some political argument in Black Panther, telling Wired, for example, “This is not a propaganda sheet. This is supposed to be exhilarating, fun to read.”

Given that too many recent superhero narratives have been overburdened by their insistence on Big Ideas, that’s a right and reasonable goal. The trouble is that there’s much more going on here than a simple thrilling romp. Try to get beyond the iconic force of that opening image, for example, and you’ll have to reckon with the triptych behind it—three distinct figures condemning T’Challa for reasons deeply embedded in Marvel comics history. Here, it’s not enough to recognize Namor the Sub-Mariner in the middle; you also have to know, as Abraham Riesman explains in his annotations to the issue, that Namor flooded Wakanda, killing thousands “[w]hile under the influence of alien intelligence,” and that, despite this war crime, Namor later teamed up with T’Challa to fight a greater threat, a collaboration that enraged the Wakandans when they discovered it. These aren’t Coates’ stories except insofar as they’re all our stories. They belong to the corporate lore of Marvel comics, emerging wraithlike from the dense fog of its decades of narrative continuity.

That same fog blankets the issue as a whole, and only those who know the terrain well will manage to negotiate it with ease. It’s perfectly possible, of course, to tell Black Panter stories without such baggage. In his mid-oughts series “Who Is the Black Panther,” Reginald Hudlin offered a spare, fun, and accessible story about T’Challa protecting his nation from an attempted regime overthrow by a thinly disguised version of the Bush administration. A little dated now, it still makes for propulsive reading, in part because it clearly frames all of its references to past storylines.

The takeaway, however, isn’t that Coates could have told a simpler story, but that he chose not to. Though it’ll be easier to say what he’s assembling—and whether it’s structurally stable—once we have more of his work in hand, this first issue plainly demonstrates his contagious fascination with the marvelous minutiae of past stories. In many ways, his Black Panther is the virtual opposite of Batman v Superman, which went so broad with its references and allusions that they were largely irrelevant. Here, by contrast, the specifics of Marvel continuity provide deep reservoirs of meaning, and Coates lets them hum in the background like Wakanda’s buried vibranium. For now, at least, that power is more a feeling than a true force. Given time, Coates and his collaborators may yet excavate it.