The principle pleasure of Netflix’s D.C. soap opera House of Cards is comparing it to our real politics and noting the ways that it does, and mostly does not, match, like a game of “spot the difference” played out against the backdrop of Capitol Hill. When the show began, glistening with the imprimatur of Netflix, David Fincher, Kevin Spacey, and Beau Willimon, it seemed like a play for prestige, a wannabe high-minded drama aiming to lift up the rock of our political system and expose the wriggling and writhing mess underneath. But House of Cards itself just wants to wriggle and writhe. Its politics are scoffable, but its entertainment value unlimited.

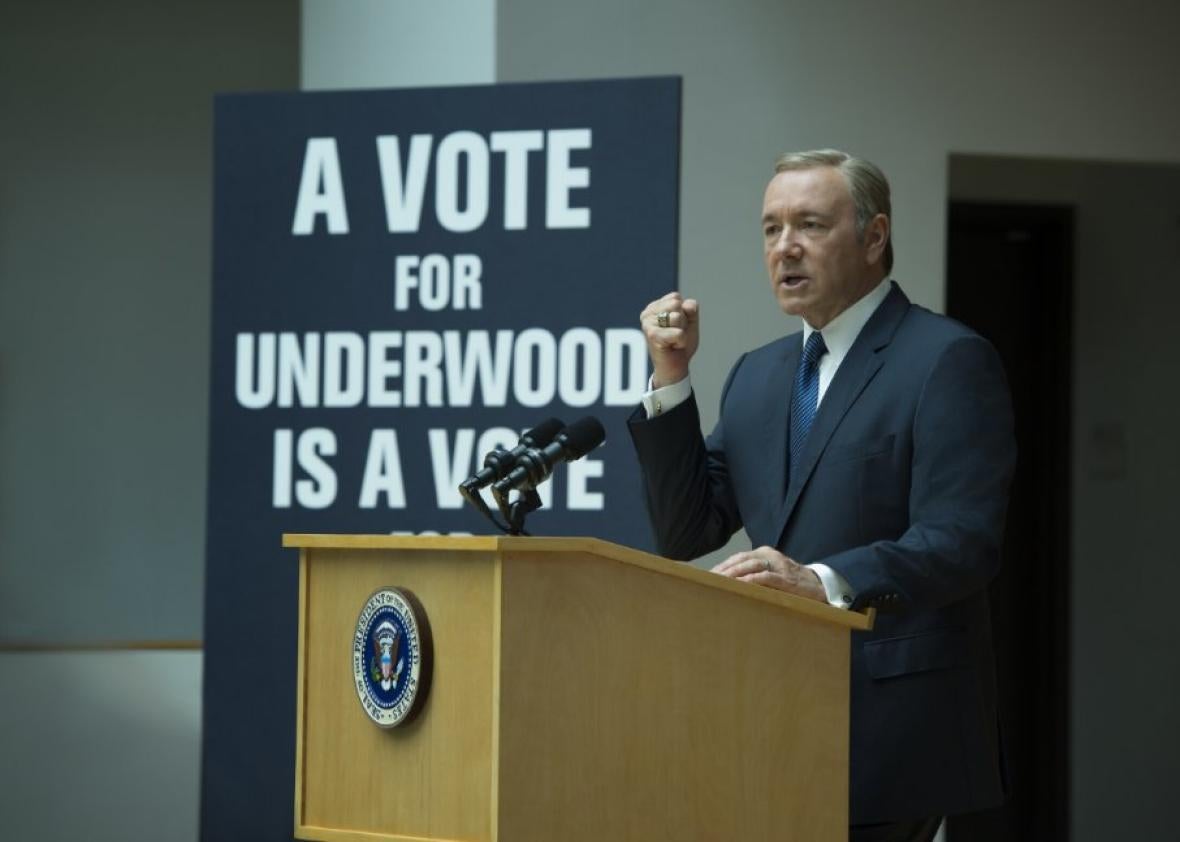

For its first three seasons, House of Cards’ version of reakpolitik was so purple, it even appealed to people who spend their days politicking. Frank Underwood, the Southern-fried Machiavelli played by Spacey, schemed and murdered his way to the presidency, aided by his wife Claire (Robin Wright), a pristine Lady Macbeth. The number of absurd things that happened in the first three seasons is too great to remember, let alone recount. The more memorable melodramatic turns—i.e. Frank pushing a tenacious reporter he had a daddy-issues-inflected affair with in front of a train—were more grounded than Frank’s maneuverings. They, at least, hewed to the over-the-top rules of soap opera, while Frank’s strategic machinations obeyed no rules whatsoever. In a political moment when a president elected by a broad mandate can’t avoid a government shutdown or seat a Supreme Court justice, Frank Underwood, a promoted vice president, can find exactly the right plan, blackmail, optics, or pressure to enact a massive piece of legislation defunding Social Security and to appoint his wife U.N. Ambassador.

But the days when House of Cards was more outrageous than our real politics are gone. House of Cards has dreamt all sorts of insanity, but even its wild imagination could not conjure Donald Trump. The new season, set during a 2016 election season, features a Democratic primary between a sitting president and a former solicitor general and a Republican party already united behind a handsome, appropriate candidate. Snooze. The first two episodes, which track Claire’s continued internal insurgency against her husband are downright sane compared with breaking news. When Frank is linked to the KKK, he, at least, immediately and fervently apologizes.

The up is down quality of our current moment reframes House of Cards. It is immediately less outré, but also less ridiculous. Is Claire’s bananas strategy to be named vice president really so crazy? (Vice President Melania could help lock up the immigrant vote!) An assassination attempt, unlike candidates insulting each other’s penis size, is at least something for which there is historical precedent. The current moment also makes House of Cards seem prescient about Frank Underwood’s lack of belief in anything but himself. In seasons past, ideologues seemed like House of Cards’ blind spot (as they do with HBO’s Veep). Washington may be overrun by venal, self-serving politicians, but many of those politicians seem to believe, often zealously. Donald Trump, like Frank, believes only in himself. Republicans, desperate for anyone but Trump, could do worse than a Frank Underwood.