Fifty years ago today, the London Evening Standard published an interview with John Lennon that became an enduring part of the Beatles’ legacy. “We’re more popular than Jesus now,” Lennon told the rock journalist Maureen Cleave. “I don’t know which will go first—rock ‘n’ roll or Christianity.”

The quip appeared in part one of a five-part Evening Standard series, “How Does a Beatle Live?” At first, no one seemed to notice Lennon’s assertion. But when a condensed version of the series was published in the progressive American teen magazine Datebook in July, it blew up like a mushroom cloud. The fallout is now legendary: public bonfires of Beatles records, protests by the Ku Klux Klan, DJs refusing to play the band’s songs, pastors sermonizing against them, and a chaotic tour that turned out to be their last.

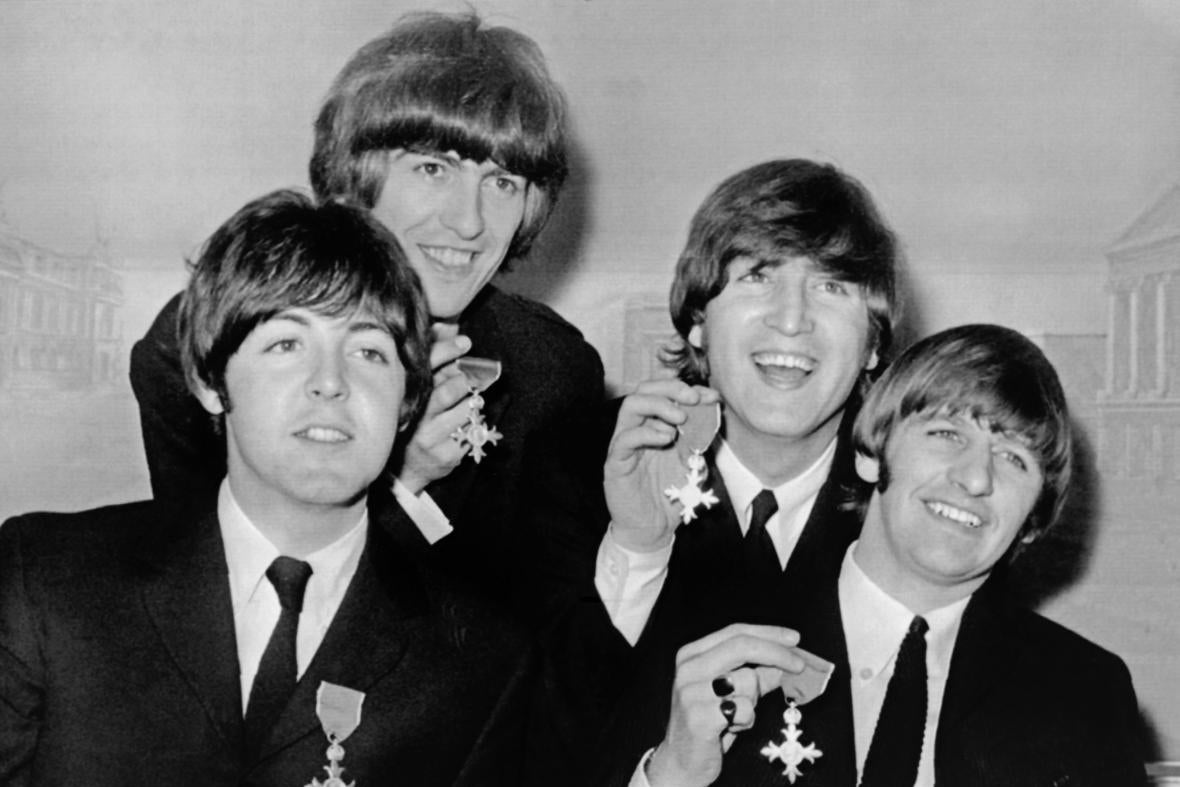

Largely forgotten, however, is the rest of the sprawling, intimate interview that was published in that series. Read five decades later, it’s a fascinating, and sometimes uncomfortable, time capsule. The band members were in their mid-20s at the time; all but Paul were married. Three years into “Beatlemania,” Cleave finds them settled into posh suburban homes stuffed with toys and collectibles and unread leather-bound books, with Ferraris and Rolls Royces in their garages. They seem to have talked easily with the journalist, a friend of the band who is sometimes rumored to be the inspiration for “Norwegian Wood.”

Like an overplayed single that loses its punch, the “more popular than Jesus” line is a lot less shocking in 2016. But a return to the original series turns up several quotes that now read as seriously pungent. “Show business belongs to the Jews,” Cleaves quotes “The Beatles” collectively as saying, in a version of her reporting that appeared in the New York Times Magazine in July of 1966. “It’s part of the Jewish religion.” (In a press conference in Los Angeles in August, Lennon tersely admitted that the quote came from him: “You can read into it what you like, you know. It’s just a little old statement. It’s not very serious.” The crowd of journalists didn’t ask him to follow up.)

Lennon also tells Cleave that he is considering sending his son Julian to a French lycée in London, but muses “I feel sorry for him, though. I couldn’t stand ugly people even when I was five. Lots of the ugly ones are foreign, aren’t they?” Ringo Starr, meanwhile, refers to the band as being so close they’re like “Siamese quads eating out of the same bowl.” He jokes of his wife, Maureen, that “I own her, of course.” She was 16 when they met—he was six years older—and “her parents signed her over to me when I married her.” Paul McCartney decries racism in America, “a lousy country where anyone who is black is made to seem a dirty nigger.” That line made it to the cover of Datebook, too, above Lennon’s Jesus quip.

Lennon’s full quote about Jesus, meanwhile, reads now as a fairly straightforward serving of amateur religious sociology mixed with a chaser of “spiritual but not religious” philosophizing:

Christianity will go. It will vanish and shrink. I needn’t argue about that; I’m right and I’ll be proved right. We’re more popular than Jesus now; I don’t know which will go first—rock ’n’ roll or Christianity. Jesus was all right but his disciples were thick and ordinary. It’s them twisting it that ruins it for me.

This was a different era of celebrity, in which famous people weren’t surrounded by a phalanx of PR people keeping them from saying anything interesting—and of course, a mob of civilians armed with iPhones ready to tweet their every word. It was also a different era, period, so the point is not that the band’s language or politics should be policed by 2016 standards. And it’s not surprising that literalists in America were going to interpret the Beatles’ mix of British cheek and intellectual-hippie earnestness without subtlety. Fifty years later, though, the remarkable thing is that only the Jesus line seemed to bother them.