Due to fear of the Zika virus, the government of El Salvador has asked women to delay pregnancy until 2018—almost two years from now. On Thursday, World Health Officials declared that the virus was “spreading explosively.” Zika symptoms are fairly mild for most people but the disease can be devastating for developing fetuses, resulting in babies born with tiny heads, a condition called microcephaly. (The connection between Zika and microcephaly hasn’t been established conclusively, but the evidence seems strong.) In a bit of cosmic cruelty, Zika has taken hold in South and Central America, where, thanks to the influence of the Catholic Church, abortion access is highly limited. In fact, El Salvador is known to have the world’s strictest abortion laws; in some cases, women have been locked up after having a miscarriage. No wonder the government doesn’t want women to get pregnant. It doesn’t want a generation of microcephalic babies on its hands—and it doesn’t want women demanding increased access to abortion. El Salvador’s request may be extreme, but it has some company; for instance, Jamaica has also suggested that women wait 6-12 months before getting pregnant.

Disasters, emerging diseases, and other news events often inspire us to seek out similar story lines in fiction, movies, and TV. The Ebola crisis of 2015 prompted many references to the 1995 film Outbreak (a film that now seems more cartoonish than scary). So it isn’t surprising that some on Twitter are invoking Children of Men—both the 1992 novel by P.D. James and the 2006 film adaptation—as a fictional precursor to the new Zika threat. In Children of Men, women simply stop getting pregnant. The cause of this worldwide infertility is unclear, but the effect is obvious: Humanity is on the verge of extinction.

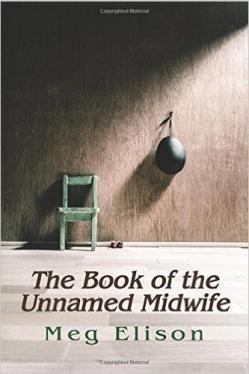

But there is a better science fiction analog to the Zika crisis: The Book of the Unnamed Midwife, by Meg Elison, which was published in 2014 In Children of Men, abortion and birth control are rendered moot; in The Book of the Unnamed Midwife, birth control and a woman’s right to bodily autonomy are central to the plot.

In Elison’s novel, a pandemic nearly annihilates the population. And the disease itself is sexist, hitting women much harder than men. The few women who remain, whether because they are immune to the disease or somehow survive it, are in danger of being taken captive, to be used as sex slaves. To make the situation even crueler, women can become pregnant—but the babies all die. And so do a lot of the mothers.

When the titular midwife recognizes the forces at play, she disguises herself as a man for protection and goes raiding for birth control—Depo-Provera shots, the vaginal ring, the birth control patch. Every time she comes across women of child-bearing age, she tries to give them contraceptives. She describes her plan here:

So is that the mission now? Angel of birth control, out to stop the crop of dead babies before it starts? Got the morning after pill, but I doubt I’ll get to use it on anyone. Wish I could get some RU486. Have the tools to do a D&C if I meet anyone who needs to abort. Can implant an IUD, but passed them over at the university. Too risky without being able to sterilize. Guess this is what I can do. Can make it easier. Can’t fix it. Nobody can. Not that different from what I used to do. Every day I remember what Chicken said, = nothing to do now but survive. Doing that now, but it’s not the only thing. Can’t be. Just gotten to the point where it feels too hard to keep trying. Every woman in labor says she can’t do it. Couldn’t stop what was happening, but I could make it easier. All the same.

Our world is not nearly so bleak, of course. But if the women of El Salvador, Jamaica, and other countries under threat of Zika are being told to avoid pregnancy until the virus is under control, then an angel of birth control is exactly what they will need. As in The Book of the Unnamed Midwife, we are facing a disease that disproportionately affects women—and in a part of the globe where reproductive choice is limited at best.