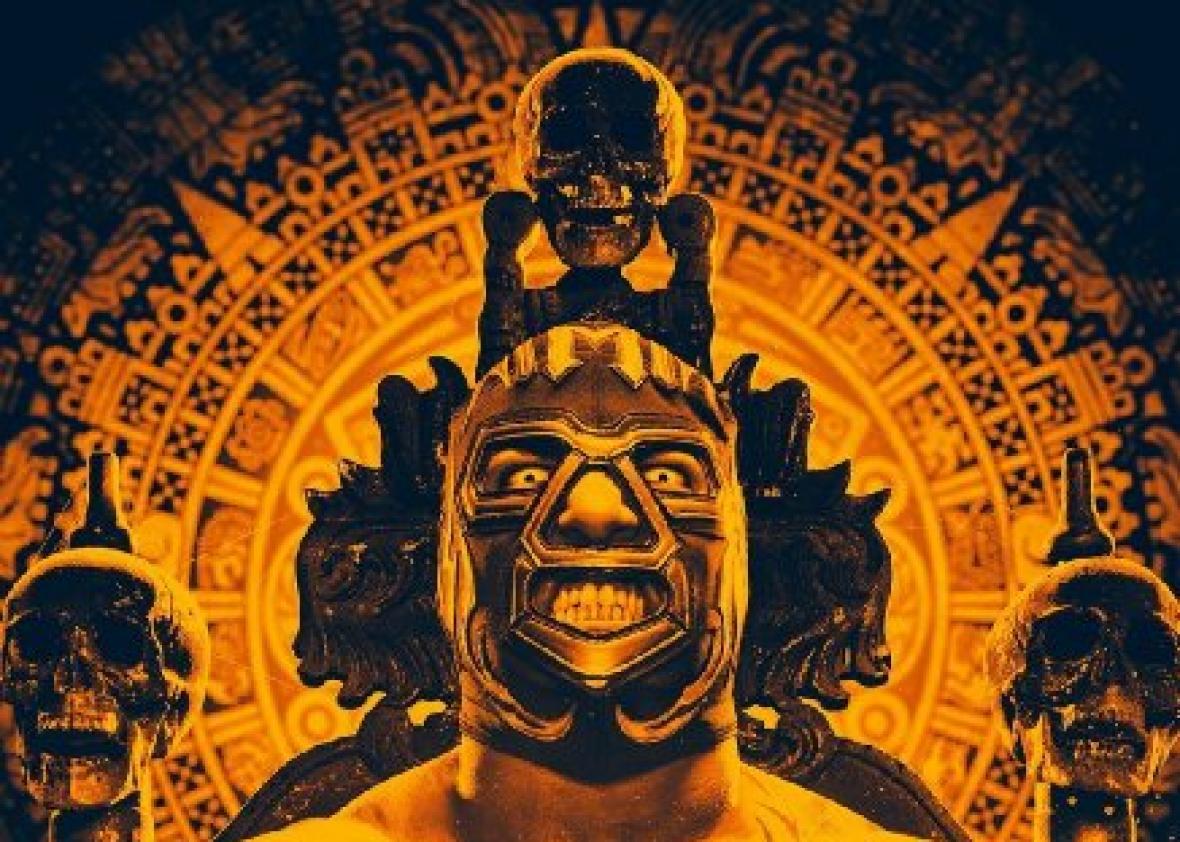

In a dank and dusty Los Angeles warehouse, two masked Mexican wrestlers go to war with one another. One of them is actually Puerto Rican, at least in real life, but you’re not supposed to know that. Instead, on this show, he’s Mil Muertes, “a thousand deaths.” As a young boy, he watched his entire family die in the 1985 Mexico City earthquake. He stayed buried in the rubble for days, only surviving by learning how to embrace death, by becoming death personified. Today, he’s a hulking and glowering mass of muscle, a merciless powerhouse bent on destruction. He carries around a hunk of broken rock from that earthquake and seems to gain some sort of mystical power from it.

His opponent on this night is Fenix, a much smaller man but one who does breathtaking things every time he comes flying off the top turnbuckle. Fenix doesn’t have the imposing physical presence that Mil Muertes does. He’s nearly a foot shorter, with just the beginnings of a potbelly and some truly unfortunate tattoos. But he represents life where Mil Muertes represents death. As the match begins, Mil rips half of Fenix’s mask off, a despicable act in a lucha libre tradition that holds the wrestler’s mask as a sacred object. The two fight into the bleachers, and Mil grabs chair after chair from feeling audience members, hurling them at Fenix’s face. And every time Fenix looks ready to die, he does something amazing. He hits Mil Muertes with a lightspeed series of kicks, or he climbs onto the railing and comes flying off with a somersault dive.

The match in question was called Grave Consequences, a bloody and brutal brawl with the same basic idea as the casket match, the ’90s WWF staple in which Undertaker and an opponent would try to stuff one another into a nearby coffin. This new version had a distinctly Mexican feel, with an eerie Dia de los Muertos parade bringing the coffin to the ring before the match. And it went down on Lucha Underground, a new pro-wrestling show on director Robert Rodriguez’s fledgling El Rey Network cable channel. It was the best pro wrestling match I saw all last year, and I saw a lot of pro wrestling matches. In fact, Lucha Underground, which returns for its second season Wednesday night, is one of the most riveting shows on TV.

For its entire 39-episode first season, Lucha Underground found some kind of gonzo greatness by throwing away the American pro-wrestling rulebook. For most of its lifetime, from its carnival beginnings to the Wrestlemania era, American pro wrestling has made it its mission to seem real, even though it was always predetermined. Sometime in the ’90s, largely to avoid dealing with state athletic commissions, Vince McMahon’s WWF admitted that it was an entertainment product and nothing more, and it then clumsily went about transforming itself into a transcendently silly physical soap opera, finding mixed success over the years. These days, the WWE is, for the most part, in one of its periodic ruts, unsure of how to tell a grand story or how real it wants to be.

That’s never been a problem in Mexico. Mexico’s pro-wrestling tradition is nearly as old as the U.S.’ But Mexican wrestling, lucha libre, has always had its own character. There are the masks, of course, and the acrobatic aerial maneuvers that Mexican wrestlers were pulling off decades before Americans even tried. But more than that, there are the themes: Good vs. evil, light forces going up against the darkness. It’s always been a passionate morality play. And with Lucha Underground, for the first time, it’s become great American television.

Lucha Underground does not waste time trying to convince you of its legitimacy. One character literally transforms into a dragon; another is some sort of ill-defined spaceman, billed as being “from the Cosmos.” Characters are killed off from time to time; one was literally fed to a monster last season. The show has all the hallmarks of prestige TV—storylines stretched out to last entire seaons, rich and varied casts of characters, comedy and tragedy sitting right next to each other. But it also approaches its pro wrestling with just the right combination of seriousness and silliness.

Lucha Underground is an offshoot of AAA, Mexico’s most popular pro-wrestling company, but it exists on its own, as a unique product. It films every episode in the same L.A. warehouse, with a similarly rowdy crowd filling up the stands each time. The backstage vignettes aren’t wrestlers ranting into microphones; they’re cinematic skits that have plenty of aesthetic similarities to Robert Rodriguez’s movies. (Rodriguez’s involvement isn’t entirely clear, but I would not be surprised to learn that he directed a few of them.) Every episode is filmed in both English and Spanish, so it can be broadcast in both the U.S. and Mexico, and the producers are happy to use subtitles for the Mexican wrestlers who haven’t yet mastered English.

On the first season of Lucha Underground, a few former WWE figures appeared, like Alberto El Patron (the former Alberto Del Rio) and Johnny Mundo (the former John Morrison). But they’re only rarely the focus. Instead, the show devotes most of its considerable energy to homegrown talents like Prince Puma, the descendent of tribal Aztec warriors who twists through the air like nobody else and who held the show’s championship for most of last season before losing it to Mil Muertes in the season finale. And the show’s greatest triumph may be the story of Son of Havoc, the masked and massively bearded biker character who went from perennial loser to crowd favorite to champion. Characters start out as jokes and then find dignity. It’s just great storytelling.

Because the show’s presentation is so slick, it demands a budget that’s hardly in line with its paltry domestic ratings. Season 1 ended in August, and for awhile, it was an open question whether its producers would find enough outside investors to bring it back. Well, they did. Since this is a wrestling show, beholden to the chaos of the wrestling industry, it won’t be quite the same as last season. But we’re lucky to have it back.