Lucifer, a new show airing Monday nights on Fox, is apocalyptically bad. The series details the exploits of the devil (Tom Ellis), who has given up his infernal domain to manage a night club in Los Angles—which is, presumably, a lateral move for him. Thanks to a series of events too ludicrous to explain, he partners with an LAPD detective (Lauren German) to help her solve crimes, occasionally taking a break to entertain her winningly obnoxious child (Scarlett Estevez). In the pilot, they puzzle over the murder of a fallen Britney Spears-like pop star. Another episode finds the pair trying to determine who shot at a shoe designer, a plot that Lucifer himself describes as “boring.” He’s right.

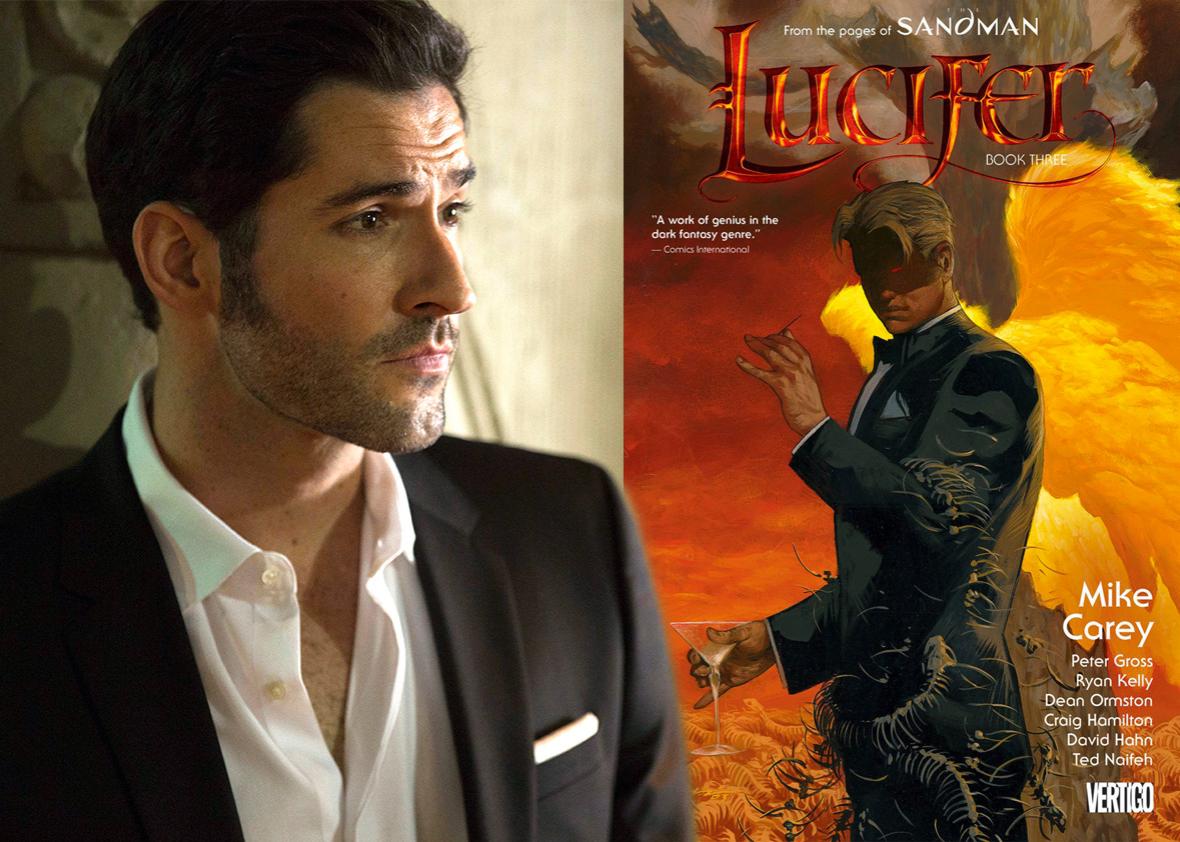

The mere existence of this show might well be proof that the Beast of Revelation already walks among us, spreading not terror but bad television. If the premise sounds stupid—and as executed here it is very stupid—rest assured that it didn’t have to be. Lucifer has it origins in a comic book series of the same name, one written by Mike Carey and illustrated by a host of accomplished artists. Published by Vertigo, the mature readers imprint of DC Comics, Carey’s Lucifer goes deep into the potential of its premise. No story about the devil solving mysteries, this is an epic about the mysteries of the cosmos itself.

Unsurprisingly, then, the staid television series borrows only the most superficial trappings from its source material. In both, Lucifer Morningstar’s club is named Lux, and in both, his second in command there is the dangerous Mazikeen (Lesley-Ann Brandt). The television series inexplicably gives its devil a therapist (Rachel Harris), but keeps the wrathful angel Amenadiel (D.B. Woodside) as his antagonist. Apart from these small details, little else has carried over. Though its procedural premise presumably takes inspiration from the odd couple charms of Sleepy Hollow, it refuses to lean into the inherent weirdness of its premise as that series does.

In fact, were it not for the one character constantly announcing to others that he is literally Satan, there would be hardly anything supernatural about the proceedings. There’s a promising moment in one early episode when Lucifer bends over to taste a pool of blood and observes that it’s “not human.” Ah!, the still hopeful viewer might think here. Is it demon blood, then? Or angel, perhaps? Alas, we soon learn the blood simply belongs to a recently deceased pig, killed for purposes as banal as they are ultimately benign. With no dark magic to be found, this is depressingly quotidian stuff, leaving one wondering why the show’s creators bothered to option such a comic in the first place.

To be fair, bringing the cosmic ambitions of a series like Carey’s to television screens was always destined to be difficult, especially in the play-it-safe climate of network television. Adaptations need not fail, though, as Carey’s own work shows. Indeed, his own series was an adaptation of sorts, borrowing characters and context from Neil Gaiman’s earlier Sandman comics in a way that at once did justice to them and made them new.

Among the most important comics series of the ’90s, Sandman follows the exploits of an embodiment of Dream. Though its goth-y pretentions sometimes feel dated today, its 75 issues are still full of richly weird ideas, not least of which is a sequence that finds the devil running an earthly piano bar. Carey takes up this premise in his own work, though he uses it less as a foundation than as a trampoline. In the process, he demonstrates that it’s possible to honor an original creation without mindlessly submitting to it, a lesson that the show’s creators seem to have understood poorly, if at all.

Carey’s series, which was was originally published as individual comics, has since been collected in a variety of editions, most recently in five massive volumes. As it does on television, the first collection of stories begins with our fallen hero is still tickling the ivories at Lux, an idyll that he soon interrupts to deal with a collection of formless beings left over from the dawn of time. By the second book, he’s dueling with a sentient tarot deck for control of a second creation, one that exists outside the domain of God himself. And as the third volume opens, we find him preparing for a duel in which the winner must eat the loser’s heart.

From there, things only get crazier. And as they do, they grow ever more delightful. Carey treats readers to biblical detectives, corrupted cherubs, vengeful Japanese deities, and celestial palaces. Much like Gaiman, he’s a master of transformative appropriation, forever shaping new narrative pantheons from the mashed-up bits of old myths. Hard to put down, the results are inventive and smart, but they’re also pulpy fun: If, as in the television pilot, someone were to murder a pop star here, it would probably be to summon a demon made from the essence of celebrity itself, not to resolve some petty jealousy.

Wacky as it sometimes gets, Carey’s storytelling always remains surprisingly disciplined. Readable in small chunks, the series as a whole is intricately plotted, every bit as elaborate as its protagonist’s own schemes. Its magical universe feels endlessly open, forever manifesting new possibilities, but tying them to old ones in ways that feel coherent and sensible. That’s apt, since it’s how Carey negotiates the series’ central conflict—a battle between predestination and free will rather than heaven and hell. A playful and brilliant bricoleur, Carey knows that there are always new ways to orchestrate familiar songs. His Lucifer ably evidences how delightful such songs can be.