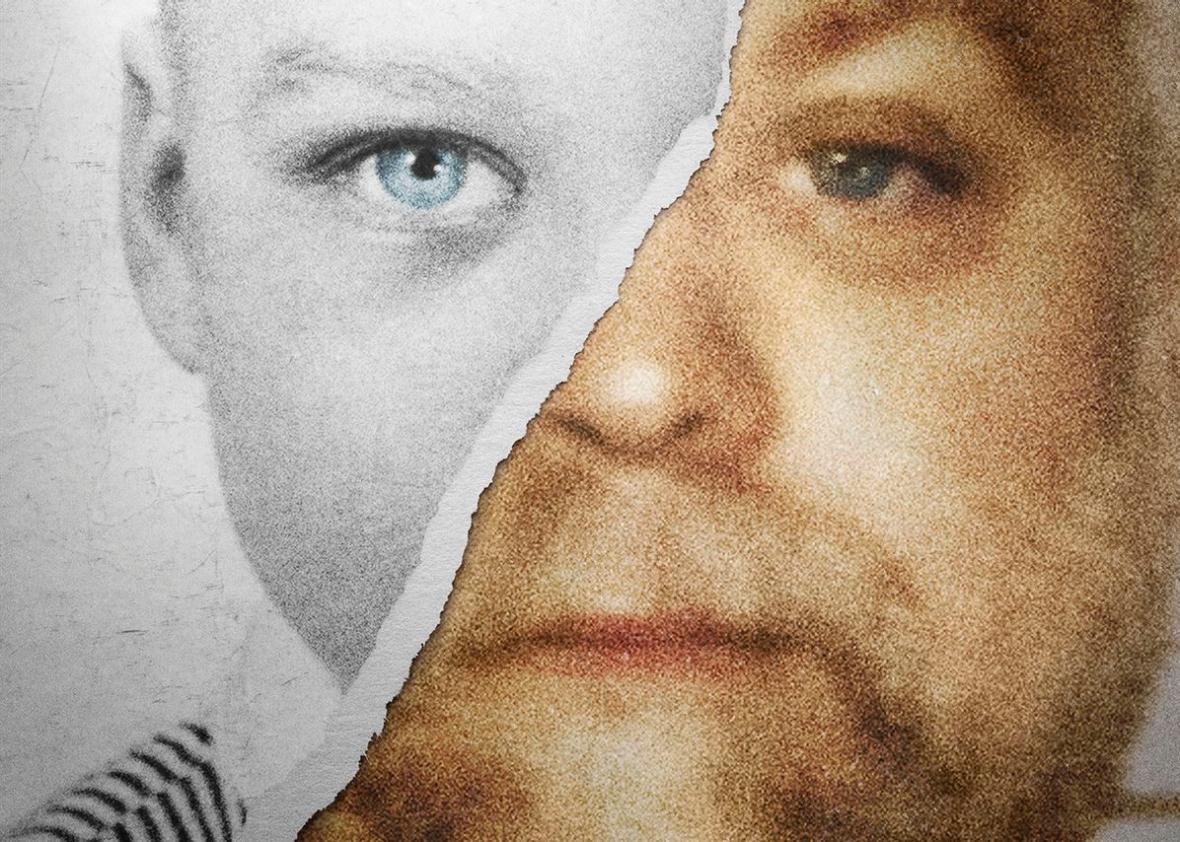

When Making a Murderer made its debut on Dec. 18, Netflix released the docuseries in the method a la mode, making all 10 episodes available at once and encouraging binge-watching. The show proved eminently binge-worthy: It follows the odyssey of a Wisconsin man named Steven Avery, imprisoned for a sexual assault he didn’t commit, exonerated after 18 years, and then tried for murder in a local criminal-justice system that appears to be hell-bent on revenge against him. It’s already inspired speculative subreddits, behind-the-scenes New York Times features, and essays on defense lawyer Dean Strang as dreamboat.

As tempting as those links are, I haven’t read any of them yet. Making a Murderer landed online the day before I left on a two-week Christmas vacation with spotty Wi-Fi. By the time I returned home, the Internet seemed to have finished watching Making a Murderer and I was—and still am—desperate to catch up. Naturally, I’ve been laboring to avoid spoilers online. News outlets are touting spoiler-free Making a Murderer content, and I’m clearly not the only one struggling with temptation:

But as much as I’m enjoying Making a Murderer, I’ve been feeling increasingly queasy about my obsessive spoiler-avoidance, and what it says about the way the show is constructed. I’m shielding myself from information about the Avery case because I want to savor the emotional payoff at the end of the series—to feel relief or (more likely) outrage in the sure hands of the show’s creators. The “plot twists” in this case are real events, and the “characters” are real people whose lives carry on after the “ending.” As a viewer, however, I know that the ending will be cathartic either way.

“This is the perfect Dateline story,” a Dateline producer says of the Avery case in Making a Murderer. “It’s a story with a twist, it grabs people’s attention. … Right now, murder is hot.” The implication of including that clip is clear: We’re supposed to be wary of such tacky exploitation. And on the surface, viewers of zeitgeisty longform crime stories like Making a Murderer, Serial Season 1, and The Jinx are partaking in something nobler than a random episode of Dateline. But if Dateline leaves viewers hanging over commercial breaks, the multiepisode format of shows like Making a Murderer dangles us over much deeper chasms. The series may be more prestige than pulp, but it delivers the same pleasure-pellets of any crime story: “That poor woman!” “Who really did it?” “Someone must pay!”

Take Episode 4 of Making a Murderer, which ends with a whopper of a plot bombshell. On camera, defense attorney Jerry Buting carefully unseals an old case file that contains a vial of Avery’s blood used for DNA testing. He finds the seal mysteriously broken, and it appears someone has used a hypodermic needle to steal a sample of the blood inside. The discovery appears to turn the previously far-fetched notion of a police frame-up job into a distinct possibility. “This is a red-letter day for the defense,” Buting says. “Game on.” Roll credits. Cue my husband and I freaking out on the couch and agonizing over whether to stay up late to watch another episode. With a cliffhanger like that, how could we not?

Of course, the cliffhangers are engineered to keep viewers engaged in the story and the issues at stake, which is surely a good thing. Reporting of this kind can shine a light on real injustice, awakening huge numbers of viewers to individual miscarriages of justice and to the systemic issues from which they flow. As Slate critic Laura Miller wrote in a 2014 defense of the genre, true crime—unlike crime fiction—is a useful reminder of the messy, imperfect nature of the criminal-justice system.

But the current wave of longform crime series seems to raise the stakes for our entertainment consumption. We’re not just killing an hour with a good murder tale. We’re spending serious time on it: watching for 10 hours, discussing it with friends, plowing through thinkpieces, signing petitions, clicking our way to the ends of the Internet. These shows’ creators know exactly how to manipulate our spoiler-obsessed culture, that dropping plot bombs which will then be obliquely mentioned all over social media is the surest way to stir up buzz. And dispensing shocking plot developments strategically, episode by episode, can easily distort the gestalt. It can leave viewers feeling like the facts of a case have revealed themselves in a way that is even more black-and-white than it really is—and leave us so fearful of spoilers that we’d rather cocoon ourselves in Netflix than understand the full, real context of a case.