What is Making a Murderer and why do many people seem to be obsessed with it?

It’s a documentary TV show, all 10 episodes of which went live on Netflix last month. It focuses on Steven Avery, a Wisconsin man who spent 18 years in prison before DNA evidence helped him clear his name—only to be accused of another crime soon after his release, this time murder. Due to the series’ unique alchemy of stranger-than-fiction, outrage-inducing details and zeitgeistiness (it builds on the true-crime mania sparked by Serial and The Jinx, not to mention came out just in time for holiday season couch potatodom), it has generated feverish interest and speculation: the standard amateur sleuthing on Reddit, the petitions for justice, and the calls for canonization of various secondary players in the story, just to name a few.

Let’s start at the beginning. How did Steven Avery get into this mess?

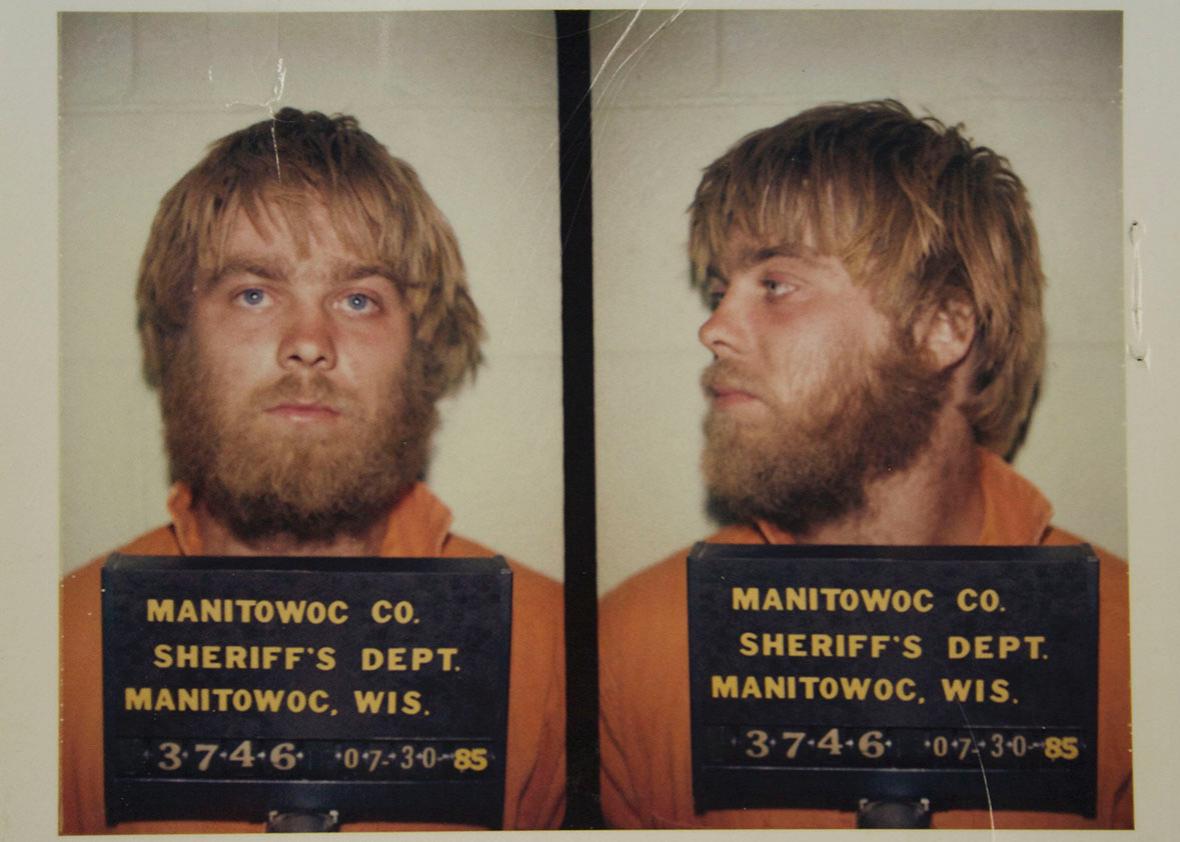

In 1985, when he was 23 years old and raising several young kids with his new wife Lori, Avery went to prison for raping a local woman, Penny Ann Beernsten. In 2003, after he had served 18 years of his sentence, DNA evidence exonerated him of the crime. It turned out that DNA pointed to another man, who may have been a suspect when the rape initially was being investigated but who police didn’t fully pursue. The Wisconsin Innocence Project, which had helped Avery turn over his case, trumpeted its success, and Avery prepared a multimillion-dollar lawsuit against Manitowoc County, Wisconsin.

Seems like a happy ending.

Except while this was going on, in 2005, a 25-year-old woman named Teresa Halbach disappeared. She’d been last seen visiting Avery. After human remains, Halbach’s car, and other evidence were found on the Avery family salvage lot, Avery was charged with murder.

So … did he do it?

Hard question. Avery has proclaimed his innocence since he was first accused. Evidence he has marshaled in his defense includes the fact that the county police took part in the Halbach investigation despite the fact that he was suing them at the time. This is where the double meaning of Making a Murderer comes in—did prison make Avery into a murderer, or did the police, by framing him? Neighboring Calumet County was supposed to take over the investigation to avoid this conflict of interest, but it didn’t exactly work out that way. Several of the officers who worked on the Halbach case were personally involved in Avery’s first case. Avery blames the police for his earlier wrongful conviction as well: As he says in the series, he believed law enforcement in Manitowoc County had it out for him and his family. One of his cousins, Sandra Morris, had previously accused Avery of running her off the road and threatening her at gunpoint, as well as exposing himself, and Morris had personal ties to the sheriff.

What evidence does Avery think the cops could have planted?

Oh, just stuff like putting the keys to Halbach’s car in his house so they could find them during a search and stealing his blood sample to sprinkle all over the car. In Avery’s evidence kit, which the police would have had access to, his lawyers found boxes that had been unsealed and a puncture in the cap of the blood’s container.

Tell me more about the Avery family and exactly what might law enforcement have against them.

Allen and Dolores Avery had four children: Charles (or Chuck), Steven, Earl, and Barbara, all of whom worked on, lived on, or lived near an Avery-owned junkyard in Manitowoc County. And many of the Averys had been in trouble over the years. Before his 1985 conviction, Steven himself had robbed a bar and committed an act of animal cruelty (specifically, he lit a cat on fire)—and some say these charges were glossed over in the series to make Steven a more sympathetic character. As Steven and his siblings grew up, the family members’ partners, spouses, and children also lived on the lot, allying themselves with, and also sometimes against, other Averys—this includes people like Barbara’s husband Scott Tadych, who testified against Steven, as well as Barbara’s sons Bobby and Brendan Dassey.

Brendan seems to be important in all of this. How did he get involved in the murder case?

In the spring after Halbach’s disappearance, the case’s prosecutor Ken Kratz announced that Steven’s nephew Brendan had confessed to being Steven’s co-conspirator in raping and murdering Halbach. The documentary portrays this confession as far from assured, however: Viewers see Dassey repeatedly questioned by his mother as to why he confessed, implying that he was coerced, attempting to take it back, and re-confessing. Brendan is described as having a below-average IQ and often seems confused about the implications of what he is saying.

Netflix original programming didn’t even exist when all of this happened. How did this show get made?

As they told Vulture, filmmakers Moira Demos and Laura Ricciardi were graduate students in 2005 when they came across a New York Times article about a man who had been exonerated by the Innocence Project only to get charged for murder. Once they found out they would have access to actual footage of the trial from the courthouse, they decided to travel to Wisconsin to see if there was enough to the story to sustain a film. They eventually ended up living there for more than two years all told. Though they were denied visitation with Steven Avery, all of his phone calls were recorded, as were Brendan’s, and they were able to use both. At first, Demos and Ricciardi thought they were making a feature-length documentary rather than a series, but as time went on and they were exposed to multipart documentaries like The Staircase, their plans changed. They pitched the show to HBO and PBS, but it wasn’t until 2013 that they made a deal— with Netflix.

Were the filmmakers totally in the tank for Steven Avery?

Not according to them, no. They’ve told various outlets that they thought the case was interesting whichever way it went. They did end up getting more access to the press-shy Averys than other media outlets that were reporting on the trial, however, which certainly affected how they portrayed the case.

I’ve heard some people complain that the series’ perspective is too lopsided. Was there evidence against Steven in the trial that didn’t make it in?

Ken Kratz told People that there were phone logs that proved that Steven “targeted” Halbach, that while in prison Steven told fellow inmates of his plans to torture women, and that evidence of Steven’s sweat was found in the hood of Halbach’s car, among other things we didn’t see in the series. Other accounts have brought up a pair of Brendan’s pants that were bleached and the bullet that was found in the garage. Whether these things can be explained away as further manipulation or represent proof of Avery’s guilt is probably still a matter of opinion.

What was the deal with the license plates?

When Sergeant Andrew Colburn was questioned by Steven Avery’s lawyers about calling in Teresa Halbach’s plates, it seemed like he may have been caught in a lie, but exactly what was going on was a little hard to parse. It was Episode 5, Colburn was on the stand, and defense attorney Dean Strang asked him about the basics of calling in license plates: “One of the things that road patrol officers frequently do is call into dispatch and give the dispatcher the license plate numbers of a car they’ve stopped or a car that looks out of place for some reason, correct?” Colburn said yes. “And the dispatcher can get information about to whom a license plate is registered? … If the car is abandoned or there’s nobody in the car, the registration tells you who the owner presumably is?” More yeses from Colburn.

Then Strang played a recording in which Colburn read off a plate number and the dispatcher on the line told him it belonged to a missing person, Teresa Halbach. “ ’99 Toyota?” he asked in the recording. Strang then asked Colburn if he was looking at the plates at the time of the call—how else would he have the plate number, or if he did, what was he calling to check on? (Redditors continue to debate what else this could mean.) Colburn’s call to dispatch was recorded on Nov. 3, 2005, two days before the car was reported found in the Avery lot. Meaning that if Colburn wasn’t telling the truth, the timeline the police said the case adhered to was also untrue, also leaving time for the tampering they say wasn’t going on.

What about the recent news casting doubt on Avery’s jury’s guilty verdict?

Ricciardi and Demos appeared on the Today Show Tuesday to announce that one of the trial’s jurors had contacted them to say that he or she had only gone along with the guilty voting because “they were fearful for their own safety.”

What was that thing about a famous singer maybe being on the jury?

Local news outlets reported that one of people selected to serve on the jury for Steven’s case was an “international recording artist” who just happened to be a resident of rural Wisconsin. One Redditor weighed in that perhaps that description was overblown: “Rick Ray was juror #11 who was dismissed after the first few hours or jury deliberation because his stepdaughter was in a serious car accident. When asked about being the international recording artist, he said that he had been in a band and they played overseas a couple of times. I think the media description of him being a recording artist was accurate but exaggerated.”

If that does not satisfy you, here is a list of “famous singers and musicians of Wisconsin,” but note that it does not distinguish between those who were born there and those who currently live there, nor really those who are living or dead, let alone those who are both alive and residing in Manitowoc County. The Midwestern state Prince lives in is Minnesota, not Wisconsin, in case you were going to ask.

What is Len Kachinsky, Brendan’s lawyer, up to these days?

For viewers whose sympathies lay with Brendan, Kachinsky fit easily into the villain role because he seemed to be serving everyone but his client. He recently defended his work on the case on Facebook (before taking down his post), and according to People, he’s still practicing and taking on new cases. Never did win that judgeship, though.

What ever happened to Steven’s wife, Lori, and their children?

Lori moved to a nearby town in Wisconsin, and coincidentally enough, married Brendan’s father, Peter Dassey. Some outlets have pointed out that Steven’s kids no longer speak to him. As the case receives widespread publicity, Lori and the kids seem to be staying out of the limelight.

Is lawyer Dean Strang single?

Nope, he’s married, and his wife allegedly finds his new heartthrob status “very, very hard to believe.” His co-counsel Jerome Buting is also spoken for.

Who are the journalists I saw on Making a Murderer? They seemed good at their job.

Journalists as well as nonjournalists have been curious about the scrum of reporters who were often shown asking questions at the trial, especially the brunette with glasses and the good-looking gray-haired guy. Romenesko, among others, IDed them as Angenette Levy, who once saved a kidnapped child while reporting, and Aaron Fox, who was just 25 at the time of the trial, respectively.

Why wasn’t more time spent on other suspects, either in the investigation or the trial?

There were other suspects, including other members of the Avery clan and, as is common in these sorts of cases, men that Halbach knew. But the defense wasn’t allowed to bring them up at the trial, due to a Wisconsin law that banned them from pointing to third parties after their initial list had been rejected by the court. Meanwhile, the Internet abounds with theories about what really might have happened.