Almost midway through New York magazine’s behind-the-scenes article about the making of Serial Season 2, Carl Swanson describes a quandary from the end of the first season: “The question quickly became what to do next. Another true crime? Something … bigger?”

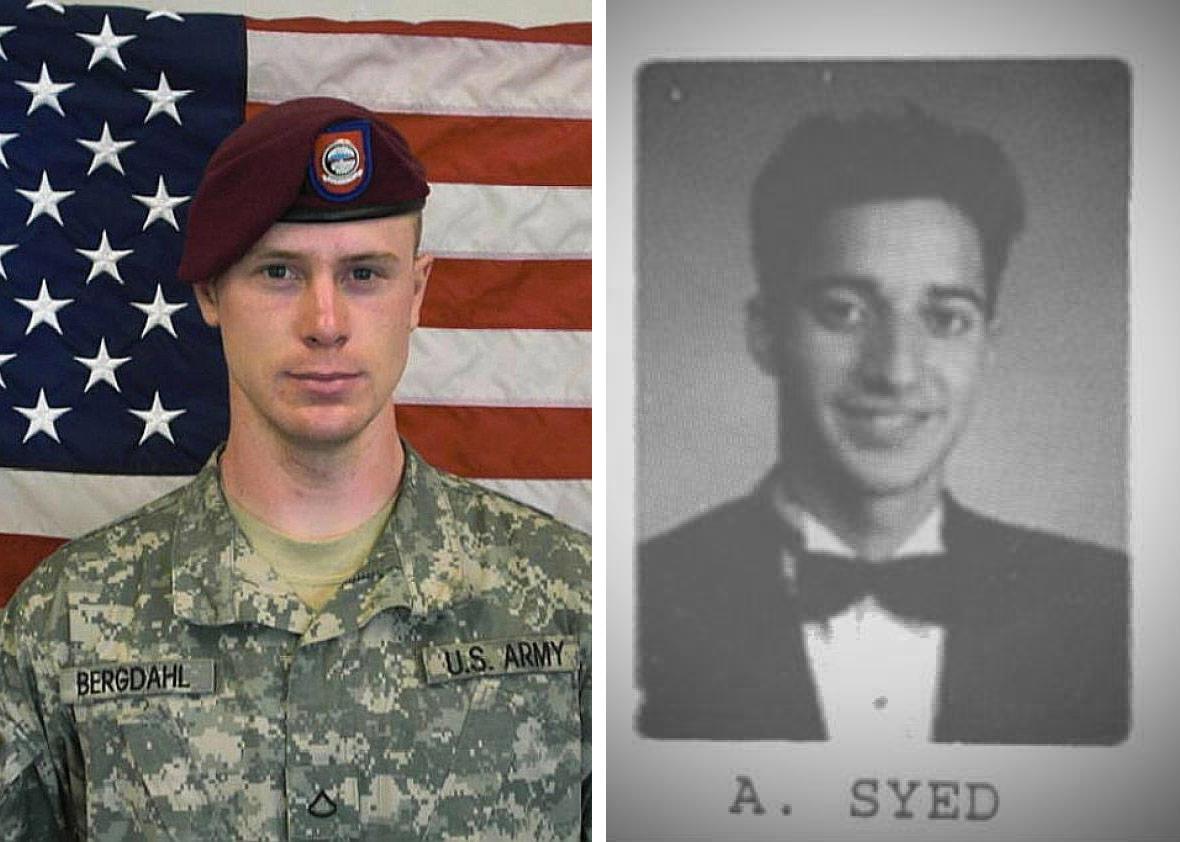

The rest of the piece charts the effects of Serial sprawl—the consequences of Sarah Koenig and Ira Glass’ choice to go with “something bigger.” The podcast is growing up. From an obscure case set in a sleepy suburban high school, it has swiveled its empathy-antennae to a huge national scandal: the capture and release of Bowe Bergdahl, an American soldier who walked off his Afghanistan base in 2009. With Season 1, facts had a linear relationship to the truth—sniffing out the first was key to the pursuit of the latter. The reality of what happened to Hae Min Lee, in other words, was all bound up in where Adnan’s car went on a particular day, and which cell phone towers pinged.

But in Season 2, facts exist on a plane parallel to truth; they’re accessories rather than necessary instruments. Sure, we’d like to know whether Bergdahl actually tamed a vicious guard dog or witnessed his captors performing a traditional dance, but we’re clear from the beginning on the general thrust of what happened: man leaves base, man falls into enemy hands, man’s freedom is traded for that of five Guantanamo prisoners. The questions Bergdahl’s story inspires are, rather, novelistic: We’re tantalized by why he left Post Mest, and what it was like, this alien world of operational tempos and stray voltage and MREs and chains-of-command. We want to catch a glimpse of life in a Taliban prison or a Pakistani ditch. If Serial Season 1 turned us into amateur detectives, the knowledge we crave now is textural and emotional, not evidence assembled into an arrow pointing to a yes-no conclusion.

What does that mean for the new season? For one thing, it places Serial’s latest project squarely in the This American Life wheelhouse. “Experiential,” slice-of-life journalism, not hard-nosed whodunit reporting, is what TAL does best. So while Serial is stretching with a big, politically reverberant saga, it is also relaxing into its peculiar and natural groove.

The other consequence of taking on a narrative that feels somewhat settled, factually, is that it leaves room for all kinds of meta-questions. To me, the most interesting of these evolutions past what’s the story—evolutions that include why the story? and what does the story mean?—is: Who owns the story?

Intentionally or not, Serial has made issues of ownership a crucial engine of its second season. Last year we all feted Koenig’s approachability and trustworthiness as a narrator; we forgot that we didn’t have a lot of alternatives. “Nobody had heard of [Adnan] Syed” when the podcast launched in 2014, Swanson notes. Koenig’s 43 hours of conversation with the convicted killer shaped our understanding of who he was. Her curation of details titrated our sympathy with our suspicion. But with Season 2, Serial represents one drop in an overflowing bucket of Bergdahl-related press coverage. The New York piece opens on Koenig pleading, half-earnestly: “Everyone wait for us to be done … ‘Nobody read anything, just listen to what we do.’” It is a wry, nostalgic nod to the podcast’s lost aura of exclusive authority. Meanwhile, Serial’s current sources are interviewing on CNN.

And the ownership question haunts Serial 2 on an even more fundamental level, because Koenig’s access to her subject is mediated by other stakeholders—namely, filmmaker Mark Boal, whose company Page One provided TAL with primary source material. “Koenig is building the new season on 25 hours of taped interviews Boal did with Bergdahl as research for a feature film,” Swanson explains. “She herself is not interviewing Bergdahl at all, which is an unusual position for any journalist to be in.” Boal, who wrote the script for Zero Dark Thirty, caught flack in 2012 for parroting CIA myths on torture’s effectiveness in fighting terror. His “mission for the second season is a bit different from that of his TAL collaborators,” we learn, in that he wishes “to do justice to military heroes,” rather than stir up empathy for a possible deserter.

So does Bergdahl’s narrative belong to Serial or Page One? To Rolling Stone, the New York Times, or some messy combination? The question feels especially charged, perhaps, because to ask who owns Bowe’s story conjures the matter of who owns Bergdahl himself. Here’s a guy who dedicated himself to the Army and then had second thoughts. In a rash burst of individualism or selfishness—take your pick—he left his post and literally spent five years as dehumanized Taliban property. Now, the United States has spirited him home only to face trial; if convicted, he heads back to prison. So it feels nontrivial to consider who gets access to Bowe, who controls Bowe’s body and his story. Where Adnan Syed dwelt mostly in a pointillist world of individuals, Bergdahl’s case revolves around institutions, each of which wants a piece of him.

Narrative ownership was clearly on Koenig’s mind when she advised Boal to turn over his Bergdahl interview tapes to This American Life. “I was like, ‘Don’t let anybody fuck it up,’ Swanson quotes her saying. “Don’t let anybody turn it into the smaller, flashier, simpler thing …. If you care about the nuance of this, the emotion of this … give it to us, or someone like us …You don’t want someone playing fast and loose with it.”

Koenig seems to hold a paternalistic attitude toward the people and narratives she covers. She trusts only her team to get Bergdahl’s story right. And yet we see a fuller picture when no one perspective prevails, even one as shaded as Serial’s. While the narrative feels more fractured now that Bergdahl is all over the media, season two is about the knotted relationship between systems and people. It makes a kind of sense that the leading man’s story has spiraled beyond a single outlet’s control.