Late in Home Alone, Kevin McCallister is fed up. Two burglars, who’ve been casing his house for days, are about to arrive and ruin Christmas Eve. Before turning his suburban Chicago home into a Rube Goldberg death machine, he says, “This is my house. I have to defend it!”

To my 7-year-old self, the mayhem that followed in the movie’s final 30 minutes was almost pornographic. An elementary schooler outwits two bumbling grownups by setting up an array of homemade booby traps: It was every timid second-grader’s fantasy.

“I think at the time, when you saw it as a kid, it was incredibly empowering in a subliminal kind of way, having this little kid beat the hell out of two men,” Daniel Stern, who like Joe Pesci played one half of the Wet Bandits, told Vanity Fair in 2013. “Like, ‘We can do it! We can take him!’”

The Chris Columbus-directed blockbuster featured a John Hughes script, a John Williams score, and a precocious Macaulay Culkin, but no single aspect of Home Alone was as memorable as its half-hour climax. On the 25th anniversary of the holiday classic’s release, I wanted to find out more about the making of the bonkers finale—so I called up John Muto, the film’s production designer.

“I kept telling people we were doing a kids version of Straw Dogs,” Muto told me. It should be noted that nothing in Home Alone is even close to as disturbing and exploitative as Sam Peckinpah’s 1971 thriller, which concludes with Dustin Hoffman’s character committing horrifyingly violent acts against a group of home invaders. But for a family comedy, Home Alone has some visceral moments. In fact, Muto figured that at least a few of its more brutal gags would end up on the cutting room floor. They didn’t.

Thankfully, there was a young cinematographer eager to capture the movie’s brand of physical comedy. Julio Macat was only 30 and coming off a gig on Sylvester Stallone and Kurt Russell vehicle Tango & Cash when he became Home Alone’s director of photography.

“They were high on me because I’d been doing all these stunts,” said Macat, who’s gone on to work on dozens of films, including The Nutty Professor, Wedding Crashers, and Pitch Perfect. “It was my first full-on studio job and I thought every day that I was gonna get fired. They were gonna figure out that I didn’t know what the fuck I was doing.”

Macat saw Home Alone as the spiritual descendant of A Christmas Story and an antidote to the typical animated specials force fed to children over the holidays. The goal was to tell the story through Kevin’s eyes. “We really got into shooting it from the perspective of a little kid,” Macat said. “I used to spend a lot of time on my knees just to see everything from that angle.” Lots of low and wide shots helped show how a child like Kevin truly views the world. “Every time you go to the house you were raised in everything seems so small,” Macat said. “We were working on the reverse of that. Everything that he’s seeing is bigger.”

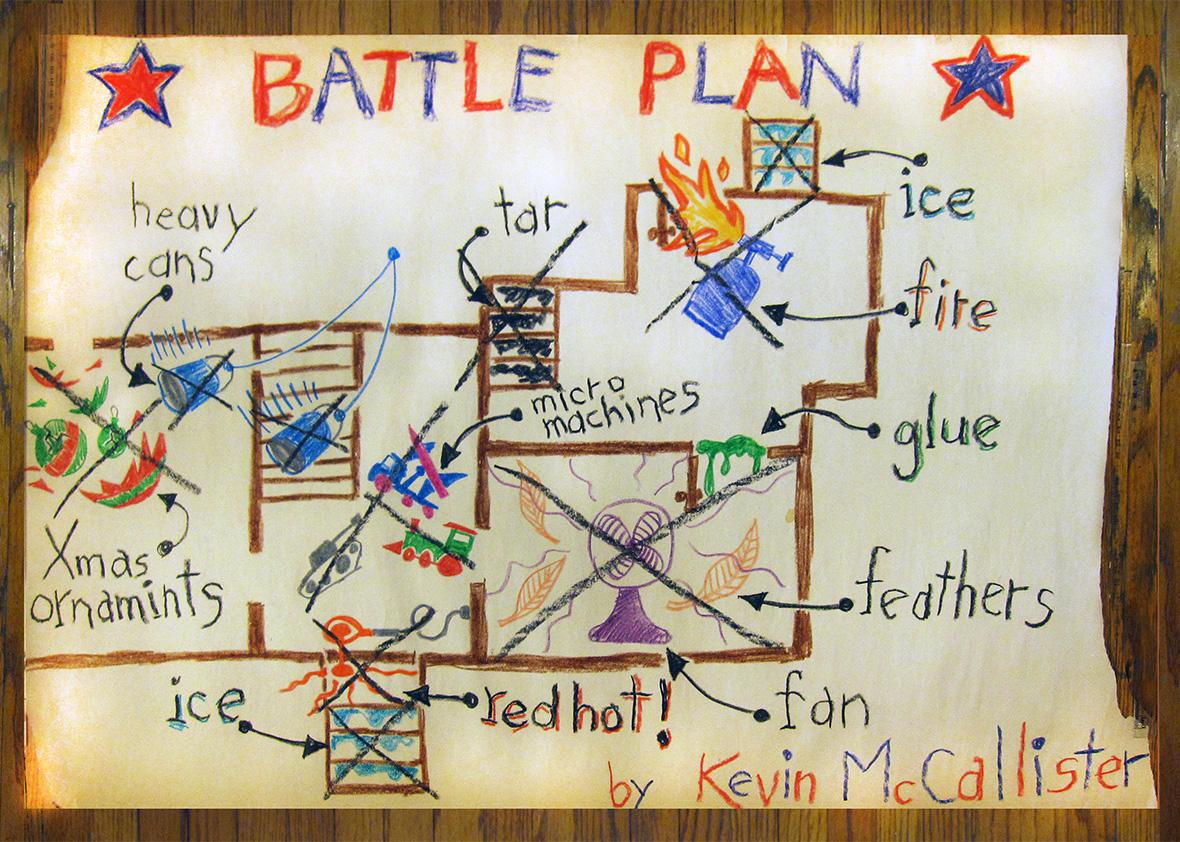

The makers of Home Alone thought very carefully about how a second grader might envision a DIY home defense system. Before rigging up his house, Kevin unfurls a “BATTLE PLAN.” To render the colorful map more childlike, Muto, a righty, drew it with his left hand. (The word ornaments is spelled wrong on purpose.) Muto didn’t just wing it while drafting the blueprint, either. Macat said that all of the traps were in the script, which the legendary Hughes wrote in less than two weeks.

The destructive power of Kevin’s booby traps probably made every homeowner who watched Home Alone cringe, but in reality, the Winnetka, Ill., Georgian that served as the McCallister home wasn’t completely wrecked by the messiest parts of Kevin’s scheme. Much of the movie was shot on a set built from scratch inside the closed West branch of nearby New Trier High School. To ensure that he didn’t miss any of the frantic action, Macat said that he often employed a “bonus” camera that was “no bigger than half a football.” At one point, it was tied to a rope and sent down the laundry chute to mimic the trajectory of the iron that hits Stern’s character Marv Merchants in the face. “It totally brought you into the gag,” Macat said.

Muto relished putting together Kevin’s tricks so that they looked dangerous but didn’t actually hurt anyone. Instead of placing a real red-hot soldering iron around the doorknob on which Harry scorches his hand, Kevin uses one made out of neon tubing. On the basement stairs, the nail that Marv steps on is spring loaded so that it retracts and doesn’t end up in his foot. When it came time for Pesci’s character Harry Lime to take the brunt of a blowtorch, the filmmakers couldn’t rely on CGI to make the gag look real. (This was 1990.) Muto opted for a version of an illusion called Pepper’s Ghost, which in this case involved setting fire to a mannequin and using reflective glass to superimpose an image of the blaze onto Harry’s head.

The actors weren’t really harmed during the making of Home Alone, but their stunt doubles had it rough. Standing in for Pesci and Stern, respectively, were stuntmen Troy Brown and Leon Delaney. While navigating the funhouse, they take several hellacious falls, including one caused by a bunch of strategically placed Micro Machines. The exaggerated spills, which practically sent Brown and Delaney into space, had one unintended effect. “To this day, you’ll talk to stunt people on other movies and they’ll say something like, ‘And then we’ll just do a Home Alone,’” Macat said. “That means that they’re gonna fall and get a lot of air.”

No stunt double could save Stern from the set’s tarantula. After Kevin accidentally lets his brother Buzz’s eight-legged pet out of its cage early in the movie, it occasionally crawls into view. As the movie draws to a close, when Kevin’s trying to escape the house, he notices Chekov’s spider on the attic stairs and drops it onto Marv’s face. During filming, Muto thought back to the moment in Dr. No when a tarantula crawls onto 007’s shoulder. “It’s one of the few times when James Bond shows any fear,” Muto said. Before the scene was augmented with shots of a spider crawling on a stunt double, there was a piece of glass separating the beast and Sean Connery. In Home Alone, the tarantula actually walks around on Marv’s face. For a few seconds at least, Daniel Stern was braver than James Bond.

After the spider spooks Marv, Kevin slips into the attic and ziplines from a window to his treehouse. The Wet Bandits eventually catch up to him, but he’s saved by his neighbor, thus wrapping up Home Alone’s insane climax.

In a recent interview with Entertainment Weekly, Columbus said that watching the end of the movie in the theater “was unlike anything I had experienced as a filmmaker because people were just screaming with laughter. It was great.”

In 1990, Home Alone was the highest-grossing movie in America. Shades of its over-the-top conclusion can be seen in other box office smashes, including Skyfall, which ends with James Bond defending his childhood home from some seriously demented bad guys. (Columbus even has acknowledged the similarities between the two.)

These days, Macat still hears from people who’ve attempted to recreate Kevin’s booby traps. “Every kid has tried shit like this in their house,” he said. “On a subconscious level, it just empowered them. All a sudden they’re not afraid of the dark or not afraid of the knock on the door. It’s a powerful thing.”