Last week, Serena Williams made headlines when she chased after and confronted a phone thief. Williams recounted the incident in a long, vivid Facebook post that was equal parts proud and inspiring. Crafted with zippy flourishes—“I was upon him in a flash!”—she accompanied her post with a photo of herself in the classic Superman ensemble. “I’ve got the speed the jumps, the power, the body, the seduction, the sex appeal, the strength, the leadership and yet the calm to weather the storm,” she wrote.

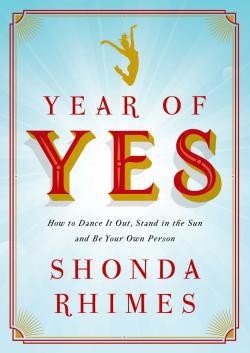

Shonda Rhimes would call this victorious post a moment of “badassery.” In her new memoir, Year of Yes, she defines badassery, in dictionary form, as (1) “the practice of knowing one’s own accomplishments and gifts, accepting one’s own accomplishments and gifts, and celebrating one’s own accomplishments and gifts; (2) the practice of living life with swagger.” Williams, she writes, has badassery in spades. “If Serena Williams tells a reporter something like, “I am the best tennis player you will see in your lifetime,” I am betting she isn’t worried that people will think she’s better than they are at tennis. Because she’s SERENA WILLIAMS.”

Rhimes is perhaps the top showrunner in Hollywood right now. ABC has carved out an entire block of primetime real estate on Thursday nights for shows that she has created and/or executive-produced with her eponymous company, Shondaland: Grey’s Anatomy, Scandal, and How to Get Away With Murder. She has inspired a zeitgeist-y movement of increased visibility for women, people of color, and the LGBTQ community known as “the Shonda Effect,” and has won numerous career-defining awards for doing so. (Not too shabby for someone whose early career included writing the Britney Spears romp Crossroads.) She knows all of this, she’s proud of all of this, and she outlines these accomplishments in her book, many times. And yet, for many years she was unable to revel in her own badassery; she dove into her work as a writer, but, as she puts it, would always prefer to stay hidden anytime an opportunity to promote herself arose, whether it was something as small as accepting a fancy party invitation or giving a speech at a conference. The thought of being a public figure made her quite literally sick to her stomach.

Jacket cover by Jackie Seow/Nick Misani/Simon and Schuster.

Enter the Year of Yes. Inspired by her sister’s off-the-cuff observance that she “never say[s] yes to anything,” on Thanksgiving morning in 2013, Rhimes made a choice to start doing so with everything that came her way, especially the things that terrify her. Yes to giving a commencement speech at her alma mater, Dartmouth College. (Of the 10 days leading up to this speech, she writes, “I become nonsensical. Irrational. I stop speaking out loud. I make noises instead.”) Yes to appearing on Jimmy Kimmel Live! (“You know what happens on live TV? Janet Jackson’s Super Bowl Boob happens on live TV.”) Yes to accepting compliments. (“I still couldn’t own being powerful. I tried hard to make myself smaller. As small as possible.”)

Rhimes guides the reader through her transformative yearlong experiment, each chapter dealing with a different personal challenge for herself, and she lets us deep inside her brain, carefully laying out all of her fears and self-doubt. As with the loquacious characters on her shows, she’s prone to baring her inner monologue through sweeping, emotional patter, sometimes digressing from the chapter’s main subject to go off on what seems like a tangent at first—but ultimately connects in some way to her larger point. Her direct-address narration is candid and friendly, almost as if the two of you were catching up over drinks. (By the end of the book, I must admit, I almost found myself wishing I were a part of her “Ride or Die” squad.) She’ll reveal something a bit odd or less-than-flattering, for instance—as when she wonders whether or not her parents, who are from Alabama, would ever have met and birthed her so that she could become the Hollywood writer that she is today had Rosa Parks not refused to give up her seat in 1955—and playfully chide the reader for judging her. She’ll also completely own up to her ridiculousness, totally self-aware: “Why, hello, narcissism. It has been pages and pages since we’ve seen each other. How you must have missed me.”

It’s this self-awareness and spiked truth that makes Year of Yes go down so smoothly, without veering too much into gushy self-help territory. I have never been a self-help, Eat, Pray, Love kinda gal—my cynicism prevents me from reading books that would be easily categorized as “inspirational” without rolling my eyes. I read this book only because my editor, who knows of my long, complicated relationship with Rhimes’ shows and my respect for her as a TV trailblazer, asked me to. But like Rhimes, I’m glad I accepted the challenge and said “yes.” Her ability to acknowledge her self-destructive thoughts are relatable, even when she is explaining that she is so terrified of speaking in public that she can’t recall anything that happened while being interviewed by Oprah. She rails against the notions of “having it all”—magically achieving a perfect balance of home and work life—while revealing, via a particularly unfortunate interaction in which she shamed a (now former) friend for having a nanny, that she was once herself complicit in promoting toxic and sexist ideas about motherhood

Of course, the outcome of her Year of Yes is predictable—Surprise! She’s joined the ranks of Serena Williams in badassery, and can now appear on a cover spread for Entertainment Weekly without freezing up or wanting to vomit. But it’s comforting—inspiring, even—to see even the most accomplished of women, who happens to be responsible for one of the foremost feminist characters on television, wrestle with how difficult it was to get to that point.