There’s nothing particularly topical about Three’s Company. The sitcom has been off the air for decades, and apart from humorous shout-outs in more recent shows like Friends (itself now over a decade old), the conversation surrounding the show died a long time ago. But in 2012, when plawright David Adjmi exhumed the show and bleakly reimagined it in his play 3C, the sitcom’s rightsholder, DLT Entertainment, issued a cease-and-desist, claiming copyright infringement. Thus began a legal battle that dragged on for several years, until a federal judge ruled this spring that the parody was a legally fair use of the original material.

On Monday night, Adjmi’s play was read once more before a live audience for the first time since its closing night at the Rattlestick Playwrights Theater three years ago. It was hilarious, queasy, and—actually—very topical.

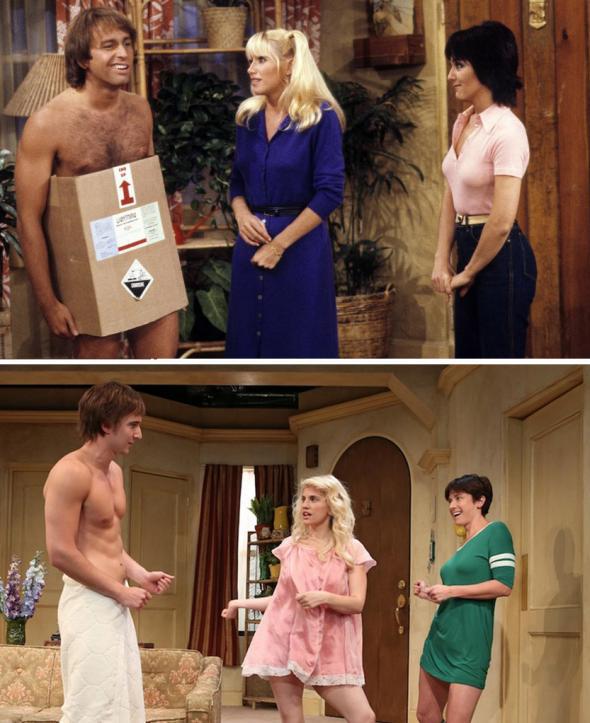

Adjmi’s characters are obvious Three’s Company stand-ins—John Ritter’s Jack Tripper becomes the clumsy Brad. Suzanne Somers’ Chrissy Snow becomes Connie. Anxious florist Janet Wood (Joyce DeWitt) becomes the even more anxious florist Linda. Womanizer Larry Dallas becomes Terry and Mr. and Mrs. Roper become Mr. and Mrs. Wicker. But Linda is far more burdened than Janet ever was; Connie constantly remarks, “Hope I don’t get raped,” subverting Chrissy’s obliviousness and her friends’ repeated concern about her getting taken advantage of. Mr. Wicker is predatory, rather than curmudgeonly. Upon rewatch, Mr. Roper’s bigotry is insidious enough—but in 3C, Mr. Wicker becomes a menacing presence.

In the play’s most insightful and heart-wrenching addition, Brad—the Jack Tripper character—is actually gay, not pretending to be gay in order to room with the girls. The incessant homophobia and ridicule he faces—both from Mr. Wicker and from Terry, whose interactions with Brad oscillate between homoerotic and aggressive—drive him to a near breaking point. “I remember watching the show when I was a little boy, and being very confused by it,” Adjmi said in an interview after the reading Monday night. “And knowing I was gay, but didn’t know exactly what that meant. What the show was telling me was that I was the punch line to a joke.”

When he came up with 3C, Adjmi wasn’t particularly concerned with how he would make a decades-old show relevant to modern audiences. “In a way, I liked the fact that it was dated,” Adjmi said. “It almost seemed so marginal that no one would look at it.” When the company issued its cease-and-desist, Adjmi was intimidated. “I completely freaked out,” he said in a panel before the reading. He didn’t know anyone who could represent him, and without allies, it seemed like the play would be shut down and kept in a drawer for good after its short off-Broadway run.

But then fellow playwright and New School College of Performing Arts professor Jon Robin Baitz (who gave the introductory speech Monday night) started a petition on his behalf. It soon collected many, many signatures—including some big names like Tony Kushner, Stephen Sondheim, and Aaron Sorkin. Baitz also put Adjmi in touch with the New York Times’ Patrick Healy, who wrote an article that highlighted the clear power imbalance that occurs when a wealthy and powerful copyright holder confronts a cash-strapped playwright. With pro bono help from law firm Davis Wright Tremaine, Adjmi fought the order, and this spring, a district court judge in New York ruled in his favor, noting that 3C makes the required transformative use of Three’s Company, making it a fair-use parody.

At the reading, audience members ranged in age from mid-twenties to much older—so, predictably, familiarity with the show varied as well. As they exited, one couple struggled to remember an episode they’d once seen on TV Land. But the play’s emotional cues—both the giddy jokes and the horribly dark moments they tended to follow—landed throughout the highly sympathetic crowd. Adjmi’s script acts like an unflinching mirror for the original, insistently fluffy show—it edges its characters into very dark territory, and then makes them manically dance, laugh, or otherwise evade their grief. These struggles will be difficult to forget next time I watch Three’s Company—and that lasting emotional impact and critical comment is the reason parody is protected speech.