Steve Jobs is not an ordinary biopic, as writer Aaron Sorkin has told the Los Angeles Times. “It’s not meant to be a dramatic re-creation of actual events,” he said. It is, instead, a looser interpretation that explores Steve Jobs’ character through his relationships with his family and colleagues. And while some of the specifics have definitely been reordered, condensed, or fabricated, a lot of the movie is very much in line with the truth conveyed by Walter Isaacson in his book Steve Jobs, on which the movie is based. In other words, this movie is a tightly woven collage of fact and fiction. Here’s a quick breakdown of which is which.

Did Jobs really deny paternity of his daughter?

It is true that Jobs initially denied paternity of Lisa Brennan-Jobs and told TIME reporter Michael Moritz that “28 percent of the male population in the United States” could be Lisa’s father. And for a good chunk of Lisa’s childhood, Jobs was barely in contact with her at all.

In the movie, a five-year-old Lisa accompanies her mother, Chrisann Brennan (Katherine Waterson), to the 1984 launch of the Macintosh. There, Brennan confronts Jobs (Michael Fassbender) to ask how he can reconcile his vast wealth with the fact that she and Lisa are on welfare. However, by the time Lisa was three (around 1981) Jobs had already bought a house for her and Chrisann. According to Isaacson’s book, a few times a year, he would stop by to discuss school options and other issues with Chrisann, but he would not go inside the house.

By the time Lisa was eight (in the movie, around the 1988 NeXT launch), Jobs was visiting more frequently—by then he’d moved on from Apple to NeXT. On some of those occasions, Jobs would bring Lisa to stop by the neighboring houses of Andy Hertzfeld and Joanna Hoffman—both of whom appear in the movie, played by Michael Stuhlbarg and Kate Winslet, respectively. Lisa lived with Jobs during her high school years, and began using the name Lisa Brennan-Jobs.

In the movie, Hoffman tells Jobs, “You must be able to see that she (Lisa) looks like you.” In real life, Hoffman told Isaacson that you could tell by Lisa’s jaw that she was her father’s daughter. “Nobody has that jaw,” she told him. “It’s a signature jaw.” Hoffman was in fact the one who insisted that Jobs do a better job as a father—a byproduct of her own childhood with an absent father. Jobs took her advice, Isaacson reports, and later thanked her for it—although he and Lisa would continue to have a tumultuous relationship.

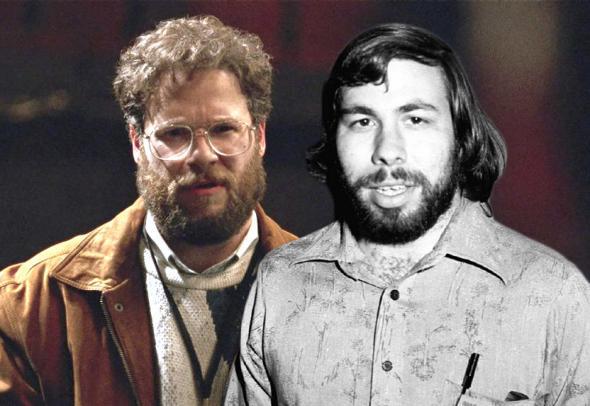

Seth Rogen in Steve Jobs (2015), and Steve Wozniak in April 1977.

Photo illustration by Juliana Jiménez. Photos by Universal Pictures and Tom Munnecke/Getty Images.

Did Steve Wozniak and Steve Jobs actually have repeated shouting matches right before product launches?

In the movie, Jobs gets besieged by a seemingly infinite stream of emotional confrontations right before launches. Woz constantly implores Jobs to acknowledge the Apple II team—and Jobs repeatedly refuses. But Wozniak, who was a consultant on the movie, says he and Steve never argued—at least not in the heated manner the movie portrays it.

In a 2011 interview, Wozniak said that he did speak to Jobs on behalf of the Apple II team, but Jobs didn’t talk to him personally about those issues. “The closest thing we ever had to an argument was when I left in 1985 to start a company to build a universal remote control,” Wozniak said, adding later, “Nobody has ever seen us having an argument.”

Was Jobs ever in line to be Time’s “Man of the Year”?

Nope. But unlike the way things played out in the movie, it seems that Jobs never realized or accepted this fact in real life.

In the movie, Jobs is angry because he thinks a colleague lost him the cover story by making Lisa’s existence public knowledge to the Time reporter he thought was working on a Man of the Year story about him. Years later, Hoffman points out the cover art—a sculpture of a computer—would have taken a considerable amount of time to pull off from conception to completion. They must have never been considering Jobs at all. It’s a pivotal moment for Fassbender’s Jobs, as he realizes that perhaps he might actually have this “reality distortion field” he’s been accused of having after all.

Jobs really had come to believe he was supposed to be man of the year, and the article was, indeed, what made his paternity of Lisa public. Jobs told Isaacson, “He wrote this terrible hatchet job. So the editors in New York get this story and say, ‘We can’t make this guy Man of the Year.’ That really hurt.” In reality, Isaacson, who worked at Time during that period, writes that this was never the case, and the “man” of the year was always going to be a machine—the personal computer.

Did Jobs really launch the NeXT without an OS—and was it really a ploy to come back to Apple?

In the movie, at the 1988 NeXT launch, Jobs relishes dishing to a reporter—off the record—all about how the NeXT doesn’t even have an operating system yet. According to Isaacson’s book, it is actually true that at the time of the NeXT launch, neither the hardware nor the operating system were ready. But the movie uses this moment as a way to highlight Jobs’ prescience, staging a conversation with Hoffman in which she realizes Jobs has actually been deliberately dragging his feet on making the new OS because he’s waiting to see what Apple needs. In reality, Apple didn’t announce its intention to buy NeXT until 1996. There is no way that Jobs delayed the OS until he deciphered what Apple needed, since NeXT was up and running, with multiple partners that were not Apple, in the meantime.

Did Jobs really have no furniture in his home?

When John Sculley (Jeff Daniels) stops by Jobs’ home in the movie, he makes a joke about Jobs’ lack of furniture. But did Jobs really live such a Spartan lifestyle? Yep. According to Isaacson, who includes a delightfully absurd photo of Jobs sitting in his practically empty living room, Jobs was such a perfectionist that he had trouble buying furniture for himself.

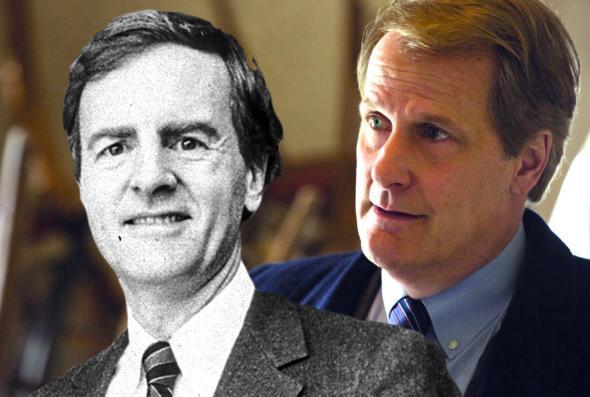

John Sculley, left, Apple’s president in 1984, and Jeff Daniels in Steve Jobs (2015).

Photo illustration by Juliana Jiménez. Photos by Marilyn K. Yee/New York Times Co./Getty Images and Francois Duhamel/Universal Pictures

Did Hertzfeld actually loan Lisa money for her Harvard tuition?

In the movie’s third act, at the iMac launch, Hertzfeld and Jobs get into a heated argument about a sizable loan Andy had given Lisa. Jobs is furious that Hertzfeld loaned Lisa money for a semester’s tuition at Harvard after Jobs told Lisa he wasn’t paying for it anymore. The two would often have ugly fights, followed by months of not speaking to each other.

In reality, Lisa borrowed money for her tuition at Harvard from a couple living down the street. But Hertzfeld loaned her $20,000 for a graduate writing program at Bennington College.

All of this, of course, did not actually take place on the day of the launch. Steve Wozniak and Andy Hertzfeld did attend the launch—Jobs gave Woz a shoutout, and, according to Isaacson, shot Hertzfeld a smile from the stage. Jobs and John Sculley, however, fell out of touch completely after Jobs left Apple. As Isaacson writes:

When a guy from the facilities team went to Jobs’s office to pack up his belongings, he saw a picture frame on the floor. It contained a photograph of Jobs and Sculley in warm conversation, with an inscription from seven months earlier: “Here’s to Great Ideas, Great Experiences, and a Great Friendship! John.” The glass frame was shattered. Jobs had hurled it across the room before leaving. From that day, he never spoke to Sculley again.

Thus, their reconciliation at the iMac launch in the film is very much false—along with their explosive argument before the NeXT launch.

Did Jobs really print out a digital painting that Lisa made as a child, save it for years, and give it to her before the Mac launch?

Nope! The painting Lisa makes on the Macintosh in the first act never happened—and so, the movie’s final moment of ambiguous reconciliation in the third act could not have happened, either.

Did the real Jobs casually stick his feet in a toilet from time to time?

Perhaps the most shocking moment in Steve Jobs: As Jobs prepares for a presentation, he washes his feet in the toilet. This was apparently the only moment in the movie that was not in the script—it was actually Fassbender’s idea. Why? Because Steve Jobs actually did stick his feet in toilets to relieve stress.

Read more in Slate about Steve Jobs: