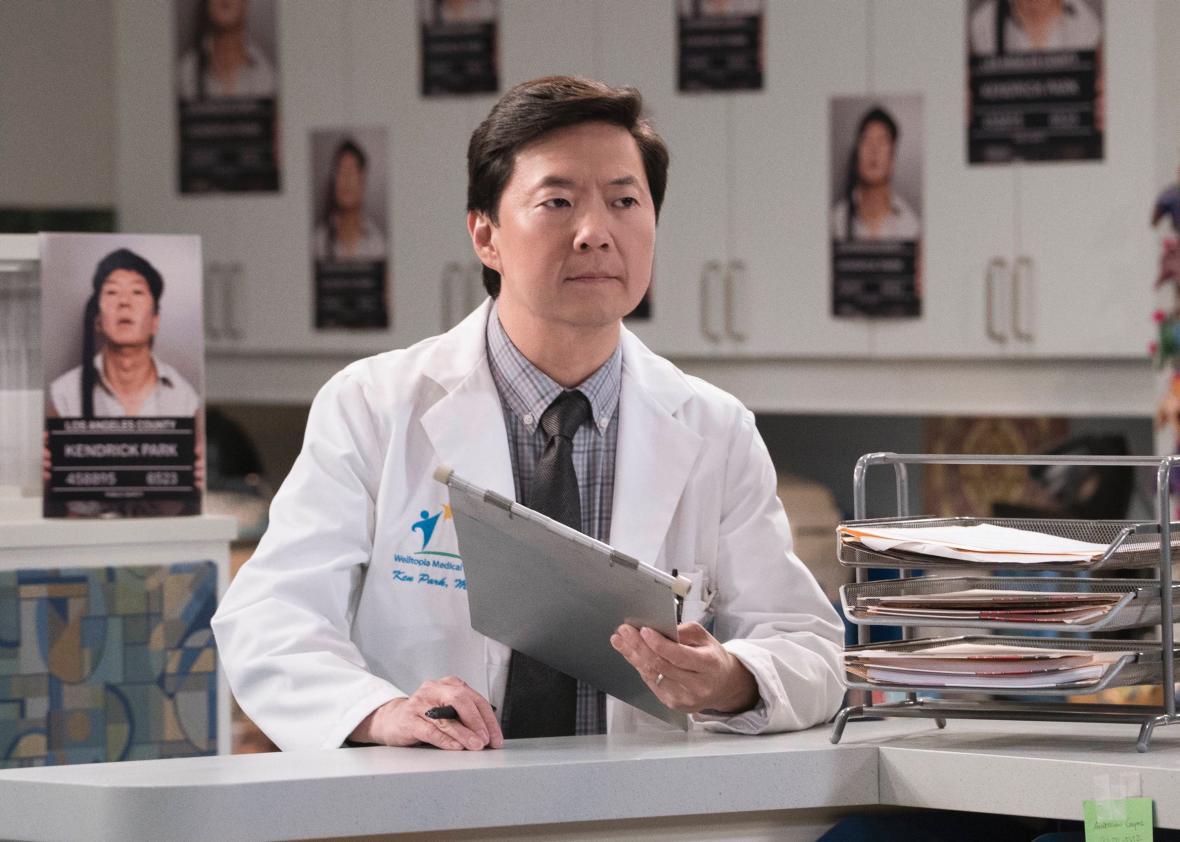

Last week was a rough one for Ken Jeong, star and producer of the just-launched ABC comedy Dr. Ken—but it ended on as high a note as he could’ve hoped: The family sitcom opened as Friday’s most-watched scripted TV show, and gave the network its biggest Friday comedy premiere of the past three years.

The ratings felt like a vindication of sorts for Jeong, best known for his hilariously over-the-top antics in The Hangover movie trilogy and in NBC’s cult hit Community. He’d been developing his semiautobiographical series for two years when ABC picked it up earlier this year. Since then, he’s been pulling 90-hour weeks to bring the project to life, fueled by six-packs of Coke Zero and a seemingly inexhaustible supply of manic willpower, But early critical buzz was not overly kind. (In classic Jeongian fashion, the comic engaged in polite, encouraging dialogue with his more civil detractors, and pointed the rest to a since-deleted animated GIF of himself making an obscene crotch-level gesture.

Slate caught up with Jeong on set at Sony Studios’ Stage 28 last week, where he was filming a scene in which Dr. Ken, dressed in formal wear, delivers a sweatily earnest standup routine in front of a gala dinner audience. The crowd initially responds with stone-faced silence—until Dr. Ken’s family breaks the ice, cheering him on and encouraging the rest of the room to join along with their laughter.

After he finished the scene, Jeong sat down to discuss, among other things, his evolution from comic relief to leading man, the early backlash to Dr. Ken, and the pressures of being one of the only Asian comics on TV.

What exactly was going on in the scene you just filmed?

It’s based on real life, from when I was at Kaiser Permanente—I used to do standup at our end of year physician banquets. So Dr. Ken is performing at the Welltopia New Year’s banquet, and in this scene he’s doing his set, these medical celebrity-impression bits like “Mr. T-Cell,” the “Christopher Walk-in Clinic,” “Kanyeast Infection,” and it’s not going over well.

We wrote 20, 30 jokes, and out of those jokes we picked three or four we knew were going to die. Joke triage! It was a lot of fun.

To go back to the very beginning: How did Dr. Ken happen?

I was approached about two years ago about doing my own sitcom, and it wasn’t a great idea at the time—it was, “Hey, why don’t you play a doctor down South?” So I responded, “Well, why don’t we just do it based on my actual background?” and they said, “Oh, okay, that’s good too.” And then we were going back and forth, should it be multicam, where we’re doing it in front of a studio audience, should be single camera, which is more like film…I definitely consider myself a single camera guy, having done movies and Community for six years. But I came out of standup, and I stopped doing that after I started getting more work as an actor, so I missed playing to an audience—I really love that instant feedback from the crowd. And the world of single cam is grueling, you know? Community, we were working 90-hour weeks, man. It’s intense.

So you wanted something that would allow a little more work-life balance?

Well, yes, but I have to say, those were also the best years of my life as a performer. I tell people Community was like my post-doctoral work in acting.

You know Malcolm Gladwell, his whole 10,000 hours thing—how you have to do 10,000 hours of practice to get good at anything? Hangover made me famous, but Community made me a much better actor.

Dr. Ken is an Asian American family comedy, but a totally different Asian American family comedy from, say, Fresh Off the Boat.

Our show is refreshingly uncultural, if that makes sense. We definitely bring in those issues—there’s an upcoming Thanksgiving episode that’s all about culture clashes—but we’re doing it in a different way. In real life, I’m Korean American, my wife is Vietnamese American, and when our in-laws come over, those aspects of us come in[to play]. But in the show, I felt the cultural aspects had to be organically introduced. Not the way a white writer might introduce it into a sitcom.

To be truthful, early on one of the white writers on the show pitched a very hacky Asian joke and I threw a fit. I’m not saying this to curry favor with the Asian American community; I’m not trying to suck up to anybody. It’s about my own artistic voice. In my life, I don’t talk like that, I don’t act like that. So I was like, “Guys, that’s not happening.”

As the star of this show, the writer, and also the source material, are you constantly thinking about these issues — about how to sensitively portray cultural issues, but also make good comedy?

Well, it takes a band of brothers to do a show. Our showrunner, Mike Sikowitz, has taught me a lot about going with your gut, about being quick and decisive about what you think is right and wrong. Because it’s okay if some of your decisions are wrong—and you know, half of them will be. That’s television. Hell, .500 is a pretty damn good batting average.

The roles that have made you popular have been really edgy and out there. Now you are starring in that most classically American family vehicle: a multicam family sitcom. Was there ever any doubt on your part that you’d be able to convince people you could do this?

Everyone knows me for the Hangover trilogy, but I’ve been in plenty of other movies, including kids’ movies. I was in Despicable Me 2, I was in Zookeeper. What [frustrates] me with critics in general is that they always forget that I’ve done a lot of other stuff.

The bigger challenge was what tone we were going to strike. How we’d balance the work side and family side of the show. But I learned from Dan Harmon on Community — he told me that when he started he knew what the show was, but he didn’t know what the show was going to be. I think critics tend to think that comedy is freakin’ math. Like, this is the Pythagorean Theorem. They’re not sophisticated enough to know that comedy is fluid, that it evolves, and these organic evolutions are what you have to embrace. Well, we’re not trying to solve a mathematical formula. Every episode is a little bit different.

How’d you decide to cast Margaret Cho as your sister?

I thought about Margaret even when we were doing the pilot. I didn’t know what role it would be, but, I was like, we must get Margaret. And what made that special was, when we decided to do it, there wasn’t even a script yet. I just texted her and said “Would you come on?” And a minute later, sight unseen, she texted back yes. She trusted me that much. And the show she did, she hit it out of the park. That night was very emotional. After her scenes, she told the audience that it was 21 years to the day that her show All-American Girl premiered. And she said, “This show, being here two decades later, validates everything I’ve ever tried to do.” It was really lovely, and Margaret—any Asian in entertainment owes a debt of gratitude to her.

Did you guys ever talk about her experience with All-American Girl, and the slings and arrows she dealt with from critics and the Asian American community?

I really wanted to have this heart-to-heart, come-to-Jesus kind of talk with her, but it was tough to do that in the middle of filming. We promised to get together and have that discussion when the dust settles a little bit. You know, share war stories, because I’m sure we’ve been through similar things.

I think historically there’s been this mentality that there can be only one Asian person at a time in comedy or drama. The roles are so limited, so there’s only one of us getting all those roles, only one person who’s allowed to succeed. That couldn’t be more untrue right now. There’s a sense of mutual support out there right now among Asians in the industry that wasn’t there for Margaret back then.

And frankly, it’s really cool for ABC to say, “Hey, we can have not just one, but two Asian American family sitcoms.” Because having more than one takes the pressure off of all of us. You don’t want to have the mantle of being the only one, like Margaret was with her show. That put her in a very difficult situation.

She had to carry all the weight.

She had to carry ALL the weight. I was talking with this critic recently whom I’ve become friendly with, and he was saying it’s been so messed up for Asian Americans in entertainment for so long that you guys are looking for a hero. He’s right—it’s like a Monty Python sketch, like in Life of Brian, where the guy goes “He’s the Messiah, I should know, I’ve followed a few in my time and he’s definitely the one.” I think that’s going about it the wrong way. I spoke to an Asian American audience last week and basically told them, “Be your own heroes.” Artists aren’t role models. If you want to do that, go into politics.

And yet people flip so quickly between saying, “This is changing everything for us, it’s so great to finally see ourselves on TV,” to saying “Because of this one thing that you’ve done that I don’t like, I hate your show and your kids and your face and I’m burning down your home.”

The thing that [frustrates] me the most about that is this: You can say “I don’t like your show.” But don’t say “You’ve set Asians back 100 years.” Don’t say “Because you showed your penis in the Hangover, I can’t get a date.” I’m like, no, buddy, you can’t get a date because of YOU. Those are your issues that you’re projecting onto others. My penis is fine. I rarely hang out with other Asian penises and have this kind of dialogue, but hey—I got a couple kids out of it.

So that kind of stupid crap, not coming from teenagers, but from credible writers, is what [hurts] Asian American entertainers when we’re in this situation. You guys are judging your own people harsher than you’d judge others, and that kind of judgment is discriminatory in its own way. I think at the end of the day you should just be judged by your work, not on what effect it might have on the world or your community.

Every show has to work out some kinks, of course, and there’s been some early critical pushback to Dr. Ken. What has that been like for you?

There were some problems of balance in that pilot script, because there’d been a hundred versions of that script by the time we were shooting it. And the people originating that story, the people I was working with before Mike [Sikowitz], before ABC, they didn’t know my story. So I think that’s a very fair comment and I’m not in disagreement.

I’m a smart guy. You don’t have to tell me when things aren’t working. I will do everything in my power to make things right—and I think I have, by subsequent episodes. But with a pilot, you’re introducing a whole world. You make it to get a show on the air; you have limited say in it, and there are a lot of cooks in that kitchen. In a way, it’s actually concerning if you have a great pilot, because it can only go down from there. After we made the pilot, I was in the room every day, keeping the same hours as all the writers, 12 hours a day. And that’s why these new episodes are better. Because I’m now surrounded with 12 hand-picked writers, who know exactly the kind of jokes and stories I want and which ones I don’t.

Needless to say, audiences’ attention spans have never been so short. You hope people will stick with a show, but in reality, they sample it, and then the ratings immediately start going down.

Well, having been on Community for five seasons and one on Yahoo, I’m no stranger to low ratings. You gotta remember, Community was up against The Big Bang Theory every week, because NBC for some reason decided to stick us against the biggest sitcom of the past decade. So I’m chill. I don’t come from an entitled silver spoon ratings background. Yes, that feeling of anxiety of whether we’ll keep airing, whether we’ll come back again every year, it’s agonizing. But it also means that every episode, every season, you never take it for granted.

I think in some ways it kind of freed Community creatively.

Absolutely, because by the end of the first season, with the ratings getting lower and lower, Dan was just like “Eff it.” And I think that led to us making the best television of the past 10 years, this side of Arrested Development. It was magical. I’d look at Danny Pudi while we were shooting and say, “Are we part of the best television on TV right now?” And he would just nod.

The role you played on Community was so different from the standard representation of an Asian American. You were Señor Chang, this insane Spanish teacher; you were very much playing against type.

All of the characters in the show were playing against type. I remember some bonehead posted something after my character was introduced, “There’s Ken Jeong, playing the Asian stereotype again,” and Dan responded to him “Really? Is a loud, abrasive, mentally-ill Spanish teacher an Asian stereotype now?” And I was like, boom, mic drop. That’s what I loved about Community—we had one of the most diverse casts on TV, but we didn’t emphasize culture. And yet, we also didn’t run away from it.

People may find Leslie Chow from The Hangover offensive, but he’s most definitely not a “stereotype” either.

The Chow role was originally written as a 60-year-old man, with no specific race involved. But unless you were a part of the production, no one knows that. And when I had the opportunity to do the role, there were extenuating circumstances in my life—my wife had cancer, and she was the one who convinced me to take it. I remember thinking to myself, if I’m going to do this, I’m just going to make it my own. It’s so ridiculously over the top, the only way to play this is to shatter it. Just to punch through it and go beyond it.

And a lot of people in the Asian American community who didn’t know the backstory of the role, they just reacted like, “There’s Ken Jeong, he’s subjecting us to mockery.” Well, I won’t apologize for it. I even made fun of the reaction in the second movie, when Chow says “I have a lot of heat on my ass—FBI, CIA, MSNBC, Asian bloggers.”

I feel like the essay you wrote about your wife and her bout with cancer—which went viral —was kind of your coming-out as a family man, to people who did not realize what you were all about. As opposed to the anarchic figure you often are on screen.

She had Stage 3 breast cancer. Even with the chemotherapy, she only had a 23 percent chance of survival, and she survived. It was one of those rare cancers where if you reach two years cancer free, you’re basically cured. And when we were privately celebrating that two-year mark, that week I got the MTV Movie Award for my work on The Hangover. The day I found that out, I wrote that piece.

How does your real-life family feel about your sitcom family?

My wife Tran, she’s been really great about it. There’s even some dialogue that we used in the show today, that my on-screen wife Allison says, about how I make her laugh, that’s why she wanted me, that’s why I was perfect for her—that’s directly from a real-life conversation between me and Tran. I run every idea that comes out of the writer’s room by her. Because I know she can make it better.

What about your kids? How old are they now?

I have no idea. No, kidding, ha, Alexa and Zooey, they’re eight years old, they’re fraternal twin girls and we were taping the Halloween episode last week and they came to the taping. They love Albert Tsai, who plays Dave, my son. Well, who doesn’t? They’re always asking about him by name, and wanting to watch any scenes featuring him. He’s a national treasure, that boy. So naturally funny, and he has such a natural charisma. He has abilities right now that you just can’t teach. He knows his comedy body, if that makes sense.

Did you guys write that role for him?

Absolutely, I wanted him so bad. He was the first person we cast; we offered it to him. In part that’s because during the casting process, there was this internal conversation—not coming from ABC or Sony—that if we couldn’t find someone to play my wife who was Asian, maybe we could cast a white actress. And I was like, we’ve got to get Albert now, because then that ain’t gonna freaking happen. If I get Albert, there’s only an infinitesimal chance that it would make sense, you know, for me to have a non-Asian wife but an Asian son.

But you did find the right Asian actress to play your wife.

Yes! Suzy Nakamura is brilliant, and she plays my wife Allison, who’s a therapist. To say that her role is to be my moral compass is not enough—she’s got her own quirks. Nutty in her own lower-key way. Which is a lot like my wife Tran, she’s normal, solid, everyone loves her, but she’s a little bit of a kook, quietly, when no one’s looking.

[Ed. note: According to Jeong, Allison is, like Nakamura, intended to be Japanese American—which adds an extra layer to the cultural disconnect between the character and her Korean immigrant in-laws, and makes the Parks the first multi-ethnicity Asian American family on primetime TV.]

What’s it like to play Dr. Ken?

Well, my character, Ken Park, is always well intentioned, and always overreacts to everything. Whereas Ken Jeong is always well intentioned, and overreacts only half the time. He’s totally lacking self-awareness; I’m painfully self-aware.

What would be your ideal reaction from viewers watching this show?

I want this show to be seen through the lens of me. I want them to see it as something more personal and in my own voice than anything I’ve done before. I remember thinking, I’ll never make the funniest show ever, I’ll never make the best show ever, but I’ll make my show. And that’s all I can do.