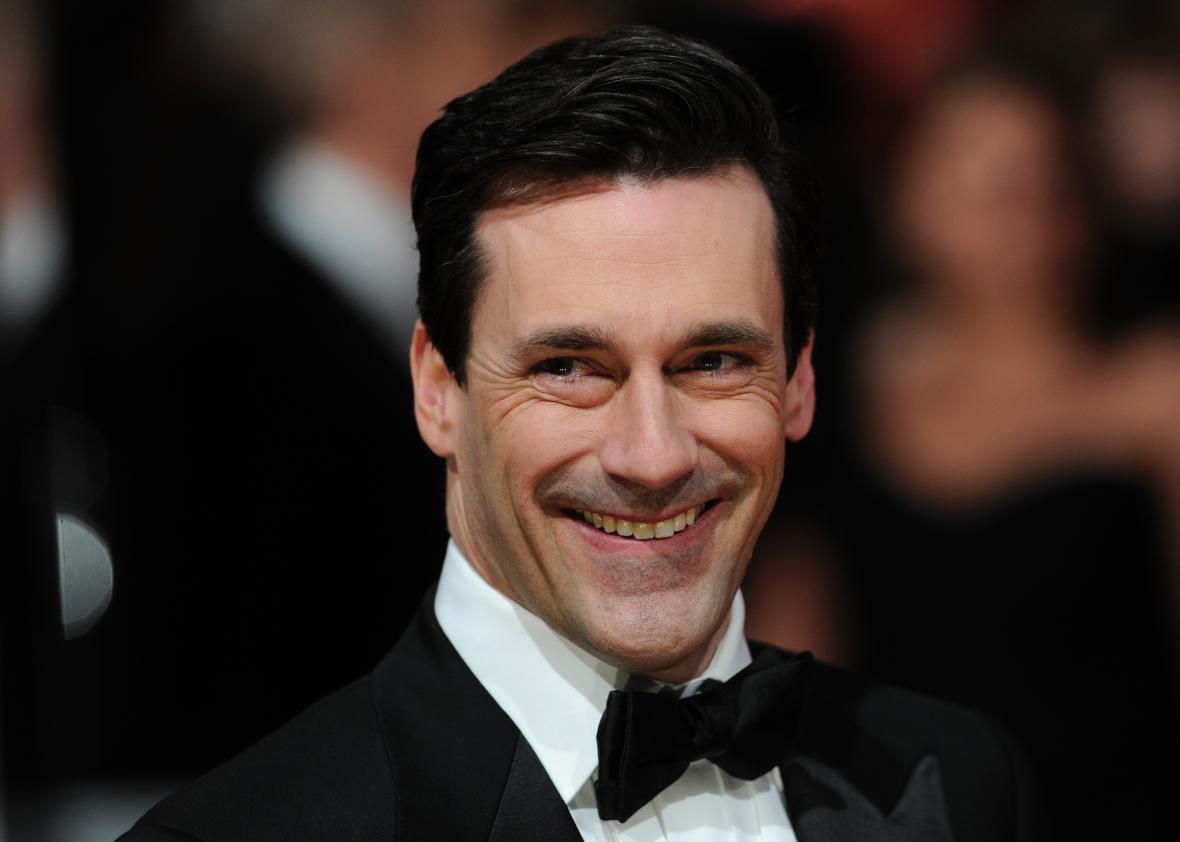

Recognition has always come late for Jon Hamm. The actor spent his 20s toiling in Hollywood, auditioned seven times to win the part of Don Draper, and for seven years in that role received zero Emmy wins for best lead actor in a drama. On Sunday, Hamm’s eighth nod in the category bore fruit, allowing him to end his Mad Men career by sinking, winged statue in hand, into a warm bath of industry acclaim.

And good for him: The triumph was sweet, overdue, richly deserved. But it also felt a bit suspect, as though the twin forces of narrative and groupthink had conspired to give him a conciliatory pat on the back. The Emmys’ revised rules permit a broader, less informed voting pool, and whispers of it being “Hamm’s time” likely secured his victory. The result was an award that felt more like an apology than an ode to craft. Which prompts the question: Why did it take this long to recognize the star of the decade’s most praised series? And what is it that made Hamm’s performance as Draper so antithetical to awards?

I’ll preface those queries with the usual caveats: Art is subjective, awards are arbitrary, and what we talk about when we talk about “acting” is rarely governed by a common criteria. It’s also worth noting the simplest explanation for Hamm’s Emmy slump: Bryan Cranston. Breaking Bad was an incredible show, Cranston’s a crackerjack actor, and it’s hard to fault the Emmys for slathering him with love during the four straight years Mad Men won for best drama.

Still, Hamm’s Emmy struggles likely had more to do with his mode of performance than his competition. As Don Draper, he was rarely privy to big emotions or outsize theatrics. Don doesn’t wallop viewers with expressive jiu-jitsu: In most episodes, his showiest gesture involves a cigarette, a furrowed brow, and a frown. That inscrutability is inherent to the character, but it’s also why viewers might underestimate the magnitude of Hamm’s achievement.

That achievement, to be clear, lies beyond the false binary of “showy” and “subtle” acting, and has to do with just how much Hamm embraced abstraction. More than anyone else on TV, the actor played an idea as much as a character. Don’s personal hiccups always signposted broader failings in the culture’s conception of masculinity, identity, and success, and Hamm managed to play an irredeemable cad while rarely acting theatrically caddish. The quietness of his performance helped prevent Matthew Weiner’s trenchant study of an era from devolving into an over-budgeted soap opera.

Mad Men worked, in other words, because Hamm used a mere handful of moods—bemused remove, stilted sympathy, tender machismo—to evoke the gamut of Don’s interior life. He located the ad man somewhere between person and parable, and, crucially, never stressed the big “moment”: We cherish Don’s dance with Peggy, but the quintessential Draper scene, which features him thinking in an empty room or talking to a full one, occurs in every episode. The term “novelistic” has been liberally applied to Mad Men’s relaxed narrative, but it’s better suited to the show’s lead: Like a character on the page, Don’s personality is conveyed not through overt expression but through the cumulative effect of mundane, redundant actions processed over a long period of time.

In a notorious pan of Mad Men, critic Daniel Mendelsohn argued that Hamm’s performance was “vacant,” the equivalent of “acting the atmosphere,” accurate descriptions used to buttress an inaccurate verdict. Hamm is vacant because Draper is a stand-in for the audience; he is acting the atmosphere because, in Mad Men, the man is inseparable from the environment. Don peddles products for a living, but his very persona is a pitch: Could you be me? Do you want to be? For how long? At what cost?

This kind of slow-building performance isn’t the kind of thing for which we usually give statues and standing ovations. But that doesn’t mean it’s any less worthy. A single furrowed brow and a frown suggest a bad day, a failed tryst. A thousand of them evoke something deeper, something like life.

Read more in Slate about the Emmys.