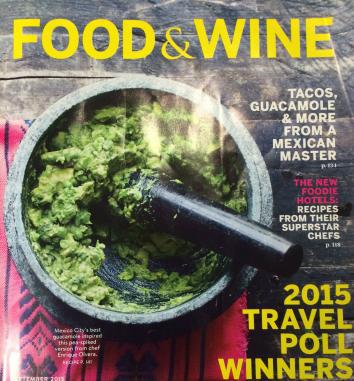

The Internet’s anger is a fickle thing. In early July, the New York Times prompted widespread outrage on Twitter after its official account endorsed a recipe for guacamole with peas. But within weeks, even the angriest commenters had moved on, finding other subjects on which to vent their ire, apparently forgetting about Peagate in the process. Case in point: When Food & Wine featured its own pea guacamole recipe on the cover of its September issue, hardly anyone made a peep about it (save for AM New York and Grub Street).

Nevertheless, my curiosity was piqued. With two publications independently deciding to endorse pea guacamole, there had to be something interesting about it. Maybe most people prefer the idea of traditional guacamole, but if you had to make the pea variety, was one way better than the other? I decided to make both the Times’ recipe and Food & Wine’s recipe to find out.

Photo of Food & Wine cover by Jacob Brogan

Both recipes were invented by enormously talented chefs. The Times’ version was co-created by Jean-Georges Vongerichten at his Mexican-fusion joint, ABC Cocina, and Food & Wine’s is based on the guacamole Enrique Olvera serves at Cosme, the New York City branch of his restaurant empire. The two recipes call for similar ingredients: Both demand roughly equal quantities of peas, though Vongerichten’s insists that they be fresh, while Olvera allows for the frozen variety. (In the interest of fairness, I used frozen peas in both batches.) The most meaningful difference is the lack of lime in Olvera’s approach. John Birdsall, whose profile of Olvera accompanies the recipe in Food & Wine, explains that Olvera omits it because the citrus “distract[s] from the avocado’s subtle acidity.”

More notable than the differences in ingredients were those of technique. With an eye toward French precision, the New York Times has the reader begin with a pea puree—processed in a blender or food processor “until almost smooth but still a little chunky”—before incorporating the offending ingredient into the avocado. Olvera, on the other hand, directs you to “mash” all of the ingredients with a mortar and pestle—first the serrano pepper and cilantro, then the peas and avocados. This more traditional method made for a rougher texture, one in which each ingredient—especially the peas—stood out. Muddling the serrano with chopped cilantro spread capsaicin across the leaves, even as it preserved small but significant pieces of pepper in the resulting dip. There were, likewise, recognizable chunks of both peas and avocado in the finished product, whereas Vongerichten’s puree led to a subtler incorporation of the various ingredients.

When I presented the two guacamoles to my co-workers, I offered them blind, refusing to identify which came from which publication. Nevertheless, their methodological variations meant their appearances varied significantly. Apart from the rougher texture of Olvera’s recipe, the lack of lime caused it to oxidize more quickly, turning it a darker—but not necessarily unappetizing—green. The Times, by contrast, calls for both the zest and juice of a whole lime, a borderline excessive infusion of citrus that couples with the peas to paint it an almost hallucinatorily verdant hue.

Perhaps it was the color that first sold my colleagues, who overwhelmingly prefered Vongerichten’s recipe to Olvera’s. Almost all of them seemed to like the Times version, and a few suggested that they might make it themselves in the future. Offering a typically enthusiastic reaction, Slate senior editor Jon Fischer described the Times preparation as “an all-star guac recipe.” And though copy chief Meg Wiegand admired the “delayed kick” of Olvera’s recipe, she dug Vongerichten’s because she likes “a lot of lime” in her guacamole. Chief political correspondent and noted foodie Jamelle Bouie gave both bowls a suspicious look before digging in, but also settled on the Times’, in large part because he too liked the lime.

The only real note of protest came from system administrator James Dasinger, who remarked, “I feel like I’m being attacked by the face hugger from Aliens, but it’s a lime.” For what it’s worth, I could relate: The lime in the Times recipe overwhlemed everything else, leaving only the sweetness of the peas and the slightly unctuous creaminess of the avocado. I wouldn’t, however, go quite as far as Dasinger, who was inclined to dismiss the whole enterprise. “I don’t know what the peas add to it,” he said, after tasting both. “It tastes like guacamole with peas in it.”

I’m not entirely sure what they added either, except, perhaps, that aforementioned sweetness. But to my mind the uncertainty is part of their charm, especially in Olvera’s recipe, where they played enigmatically off the other tastes and textures. If I make pea guac again—and I very well might—it’ll be out of a desire to solve that riddle, not because I know what it means. And when I puzzle over it, I doubt that I’ll follow either Vongerichten or Olvera’s recipe exactly. I like the punchy raw serrano in the latter, but I’ll probably squeeze in at least a little of the lime from the former. And though I’ll still mash them with a mortar and pestle, I might not put in quite so many peas next time.