Nancy Drew—the eternally teenaged detective who has appeared in hundreds of books since The Secret of the Old Clock was published in 1930—recently turned 85. Over the years, dozens of authors have penned the sleuth’s adventures under the pseudonym of Carolyn Keene, and she has been the subject of TV series, movies, graphic novels—even a line of video games. Her influence is so wide that not one but three Supreme Court justices have cited her as a childhood hero. It’s no wonder then that the 85th anniversary milestone stirred up nostalgic media coverage and has been celebrated with conventions as far-flung as Iowa, Ohio, and New Jersey.

But last week marked another, quieter anniversary for Nancy Drew: what would have been the 110th birthday of Mildred “Millie” Wirt Benson, the first author ever to write under the name “Carolyn Keene.” Despite having produced numerous children’s books under a variety of names, Benson herself is not widely known—which is unfortunate, because as a gutsy journalist, aviator, and feminist (though she didn’t like to call herself one), she was one of the most interesting YA writers of all time.

Benson ghost-wrote 23 of the first 30 Nancy Drew books for the Stratemeyer Syndicate, the publisher also behind The Hardy Boys and The Bobbsey Twins. She became involved with the series after answering a trade ad placed by the Syndicate’s founder, Edward Stratemeyer. In Girl Sleuth: Nancy Drew and the Women Who Created Her, Melanie Rehak examines the contributions Benson made to the now-iconic character. “She gave Nancy many of the qualities we remember so fondly and fiercely, like her determination, her intelligence, her self-reliance and her athleticism,” Rehak told Slate in an email. “Stratemeyer hired Mildred because he wanted someone who could infuse Nancy with these things, and he could tell Mildred was a go-getter from the moment she answered his ad.”

Though she wrote many other books in her lifetime, including her own Penny Parker mystery series, Nancy Drew was by far Benson’s greatest literary success, much to her surprise. Jenn Fisher, an author, consultant, and president of the Nancy Drew Sleuths, met Benson in 2001. “Even at that time, she didn’t quite get what all the fuss was about,” said Fisher. “[Writing Nancy Drew] was a job to her. It was a job she’d enjoyed doing, but the whole phenomenon that grew from 1930 to present day—no one would have ever expected Nancy Drew to endure for that long.”

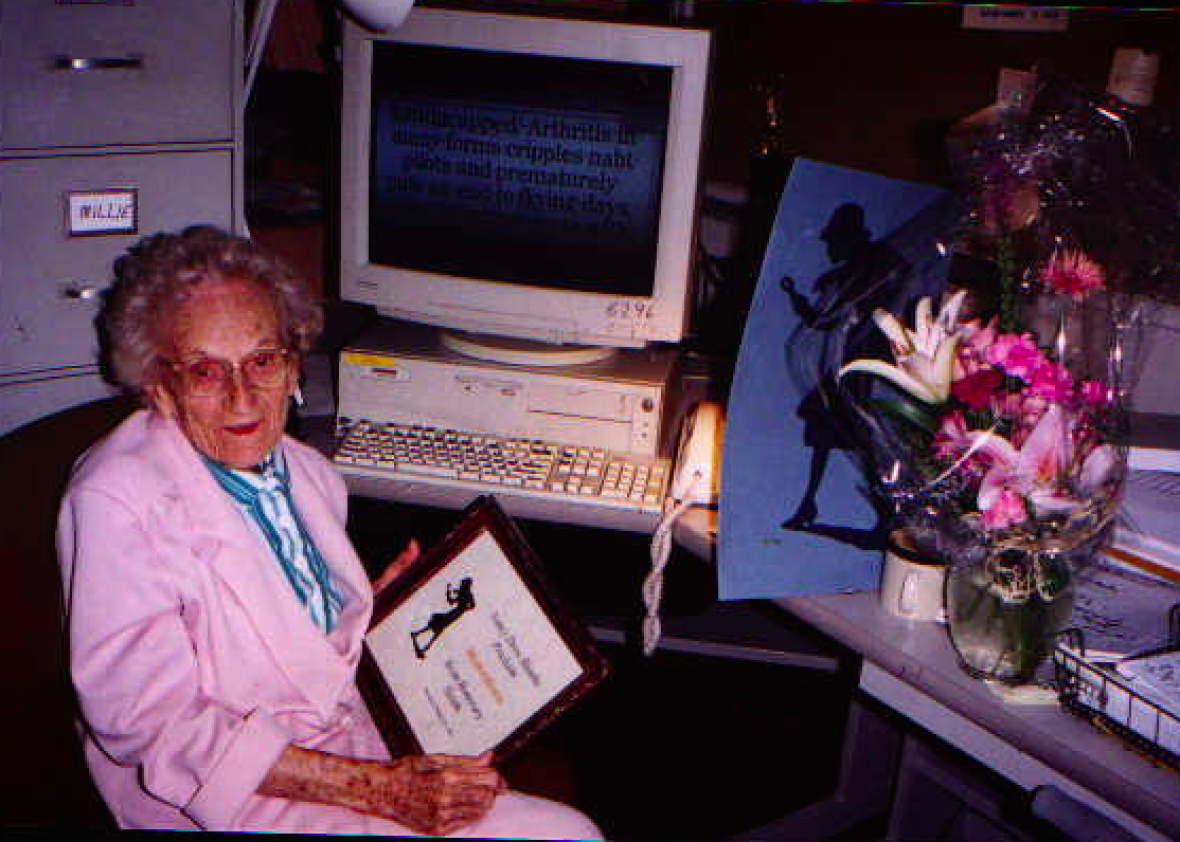

Scan courtesy of Jenn Fisher.

Fisher, who is currently in the process of writing Benson’s biography, hopes to shine a light on Benson’s life beyond Nancy Drew. Just 24 years old when the first was published, Benson, then Mildred A. Wirt, was also a tenacious reporter, for the now-defunct Toledo Times, and later for the Toledo Blade.* She worked there, despite her failing eyesight and a tendency to fall asleep at her desk, until her death in 2002, aged 96, and was at work on the day she died. She outlived both her journalist husbands, first AP reporter Asa Wirt, then her Toledo Times editor George Benson.

Even in the earliest days of her journalism career, Benson was tenacious. “In the ’40s, when she started working at the Toledo Times, she was a court reporter. She got the job because a lot of men went off to war, and they were starting to hire women,” said Fisher. When female staffers were told that when the men returned, the women would likely be out of a job, Benson only worked harder, and was competitive with her male colleagues. In her determination to get a story, she became notorious for parking herself outside councilmen’s office doors. One such councilman was so desperate to avoid talking to her, the story goes, that he climbed out his office window rather than face her questions.

Among the many pieces that she wrote for Blade were stories of her Iowa upbringing, a column on aviation—she got her pilot’s license after her second husband’s death in 1959—and, later, one geared toward senior citizens. Current Blade staff writer Tahree Lane first met Benson when Lane started at the paper in 1984, and they both worked the night shift, writing obituaries. “She was a real force to be reckoned with,” said Lane, recalling how Benson, just five feet tall, would trade barbs with then-editor Ray Jankowski. “And she was one of those rare, enviable writers who can write in her own voice.”

Some of Benson’s greatest adventures happened while she was in her 50s and 60s. She made numerous trips to Central America, including the Yucatán Peninsula in the 1960s, traversing the jungle in a Jeep, canoeing down rivers, visiting Mayan sites, and witnessing archaeological excavations. She had been an active swimmer since her college years and would often take a dive at the Toledo Club before going to work at the Blade. She saw Halley’s Comet twice in her lifetime: first as a child in 1910, and then again in 1986.

Benson remained largely unknown outside her circle until she testified during a 1980 trial for a case involving Nancy Drew publishers—the first public acknowledgement of her involvement with the series. Simon & Schuster and Grosset & Dunlap later officially recognized her authorship of Books 1 through 7, 11 through 25, and 30, in 1994. Benson subsequently became a legend for Nancy Drew fans. In an interview with Salon in 1999, the journalist, then 94, discussed receiving fan mail from around the world. “The original fans now are in their 60s and 70s. But they give them to their grandchildren and I hear from them.” Lane remembers the steady stream of visitors Benson received in the newspaper’s office, all on a pilgrimage to meet Nancy Drew’s first author. “Millie liked the little girls who came to see her the best,” said Lane. Benson would even put some of her visitors up at a hotel and take them out to dinner.

Nancy Drew has changed a bit since Benson’s first renditions of the character. The writing process at the time, Rehak explained, involved a lot of back-and-forth between writer and publisher: “[Edward Stratemeyer] would send her an outline for a story, which was usually a paragraph or two explaining the major plot points and characters, and then she would work up a draft of the story.” When Stratemeyer’s daughters, Harriet and Edna, took over the Syndicate in 1930, Nancy’s character was revised to make Nancy older—she was previously only 16, more reckless, and not as wholesome.

“[Harriet] made her into a traditional sort of a heroine. More of a house type,” Benson told Salon. “And in her day, that is what I had specifically gotten away from. She was ahead of her time. She was not typical. She was what the girls were ready for and were aspiring for, but had not achieved.”

Scan courtesy of Jenn Fisher.

Benson famously preferred her other girl detective, Penny Parker, who in many ways was Nancy’s younger, edgier counterpart. Brash, brazen Penny bears far more resemblance to the pre-revision Nancy Drew, and even more so to Benson herself; in addition to solving mysteries, Penny is a reporter with the same sense of adventure that Benson had during her life. I’m the first to champion Nancy Drew’s importance on the YA lit that followed her—her legacy lives on tenfold in modern girl detectives, the Cam Jansens and Sammy Keyes-es that children and teens still read about alongside their 1930s predecessor. But it is still a shame that Nancy Drew, not Penny Parker or even Mildred Wirt Benson, is the only one who is remembered today.

*Correction, July 14, 2015: This post originally misstated that Mildred Wirt Benson was 25 years old when the first Nancy Drew book was published. She was 24.