In 1863, a North Carolina woman named Marinda Branson Moore published a new geography book for “Dixie children.” The Raleigh-based publishing company Branson, Farrar and Co. printed 10,000 copies. The text covered topics like seasons, latitude and longitude, and the Confederacy itself (“President Davis is a good and wise man”). Lesson 10 covered “Races of Men”:

The African or negro race is found in Africa. They are slothful and vicious, but possess little cunning. They are very cruel to each other, and when they have want they sell their prisoners to the white people for slaves. They know nothing of Jesus, and the climate in Africa is so unhealthy that white men can scarcely go there to preach to them. The slaves who are found in America are in much better condition. They are better fed, better clothed, and better instructed than in their native country.

The New York Times reported soberly on the book at the time: “How far the prejudices thus implanted in youthful minds will develop themselves is a question of interest.” Today, Moore’s book is even more painful to read. And its noxious brand of Confederacy-worship is fast receding into history. In the wake of the racist shooting of nine black church-goers, we seem to be witnessing the last gasps of the publicly sanctioned flying of the Confederate flag. The governors of South Carolina and Alabama called for its removal from near the capitols; Georgia wants it removed from license plates.

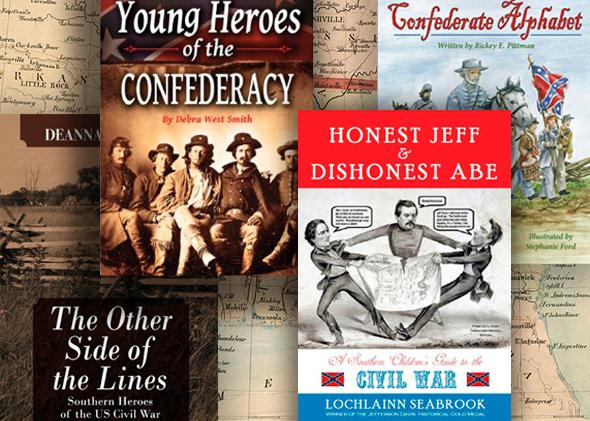

But “Southern pride” and Confederate defiance aren’t transmitted only through publicly flown flags. As Moore knew, they’re also sustained in the stories people tell their children. And although language has softened since her day, you can still find books written for children that openly celebrate the values of the Confederacy. I bought a handful of them to find out what kind of books are available to “Dixie children” in 2015.

Rickey E. Pittman’s 2011 Confederate Alphabet (all the books I mention here are available on Amazon, but I’m opting not to link to them) is a colorfully illustrated hardcover written by “a Civil War reenactor, public speaker on issues and topics related to the War Between the States, and musician.” The book is dedicated to Mason and Davis, “my own little Confederates.” The illustrator’s bio indicates that she, too, is a re-enactor.

Those mourning the receding of the Confederate flag will find plenty of comfort in Confederate Alphabet. One illustration depicts the brutal general Nathan Bedford Forrest, later the first grand wizard of the Ku Klux Klan, hoisting a large Confederate flag. A rhyme accompanies it:

F is for the flags

Of the old Confederacy;

And for Nathan Bedford Forrest

A devil to every Yankee!

A group of soldiers waves the flag again near the end of the alphabet, on a snowy battlefield littered with blue caps in the foreground:

An X is on the Battle Flag.

It is St. Andrew’s Cross.

Held aloft through smoke and storm,

Its meaning won’t be lost.

The only prominent American flags in the book are wielded by Yankees, like the ones who represent the letter Y:

Y is for the Yankees,

The enemy in blue,

Invading beloved Dixie

To conquer and subdue.

There are several black figures in Confederate Alphabet. One is a soldier eating peanuts with three white friends in the entry “G is for goober peas”; in an illustration of the siege of Vicksburg, an apparent slave woman comforts a frightened white girl. And “J is for Jim Limber,” a young black boy who lived briefly in the home of Confederate leader Jefferson Davis. As Pittman’s rhyme goes, his “story should be told.”

In another picture book, Jim Limber Davis: A Black Orphan in the Confederate White House, Pittman himself tells it. In Pittman’s version, Limber is welcomed as an equal into the Davis family. Jefferson’s wife Varina and her “maid” Ellen feed, bathe, and clothe the boy after rescuing him from a brutal beating. The next day, a kindly “President Davis” warmly informs the boy that “we want you to live with us and be a part of our family.” When the Davis family flees Richmond, cruel Yankee soldiers seize Jim and parade him in front of Northern crowds. The story ends with the Davis family kneeling together in prayer “that Jim Limber was safe and happy and that he would someday return home.” An epilogue states that the family searched for the lost boy for many years.

The actual historical record on the young boy is thin, and suffice it to say, Pittman is loosey-goosey with the details. Varina’s “maid” Ellen was a slave, Limber may not have been the boy’s real name, and it’s unlikely that he was treated as a full and equal Davis son. According to historian John Coski, there’s also no evidence that the family searched seriously for him after the war. But the prettified version of the story advanced by Pittman is a favorite of modern Confederacy defenders; Limber is featured in a statue at the Jefferson Davis Presidential Library in Mississippi, and his story appears in books like The South Was Right! (“The deep respect and love that President and Mrs. Davis had for people is clearly shown in the story of little Jim Limber ‘Davis.’ ”)

The same themes—misunderstood rebels, aggressive Yankees—can be found in some books for older readers. There’s The Other Side of the Lines: Southern Heroes of the U.S. Civil War, and Lochlainn Seabrook’s 2012 Honest Jeff and Dishonest Abe: A Southern Children’s Guide to the Civil War, which is intended for Southern parents “fed up with the Yankee myths, distortions, lies, and anti-South propaganda your child is being taught at school about the Civil War.” Seabrook is prolific, with a particular obsession with Lincoln, the subject of books like The Unquotable Abraham Lincoln and The Great Impersonator! 99 Reasons to Dislike Abraham Lincoln.

Then there’s Debra West Smith’s Young Heroes of the Confederacy, a subtler but still cringe-worthy ode to gallant young Southern men and their brave young women. In one chapter, readers are told that the children of a particular plantation-owning family were always taught to respect their slaves; on the next page, the patriarch is horse-whipping a cook. But all’s well that ends well! His daughter Bailey intervened, and “as far as Bailey knew” the cook was never punished again. In one of the book’s rare direct mentions of slavery, Smith compares slavery to a foreign diet: “Whether we grow up eating snails in France, sushi in Japan, or crawfish in Louisiana, the foods we know are what we consider to be ‘normal.’” True so far as it goes, but Smith never quite gets around to saying directly that slave-owners, “known from their diaries and letters to be moral people,” were doing anything worse than eating something icky.

Perhaps it’s necessary to state the obvious: These books are pitiful. They are poorly illustrated and poorly written, with muddled history and muddled thinking. (“Raiders” does not rhyme with “anger,” Rickey E. Pittman.) They dribble forth from fringe Southern presses, and there’s no indication they sell as well as Moore’s geography book seemed to have done. But their mere existence says something about the persistence of ugly myths long after the broader culture has moved on. Somewhere, a child is hearing a bedtime story about kindly Jefferson Davis and brave Nathan Bedford Forrest. This toxic version of the South may not rise again, but its stories linger on.