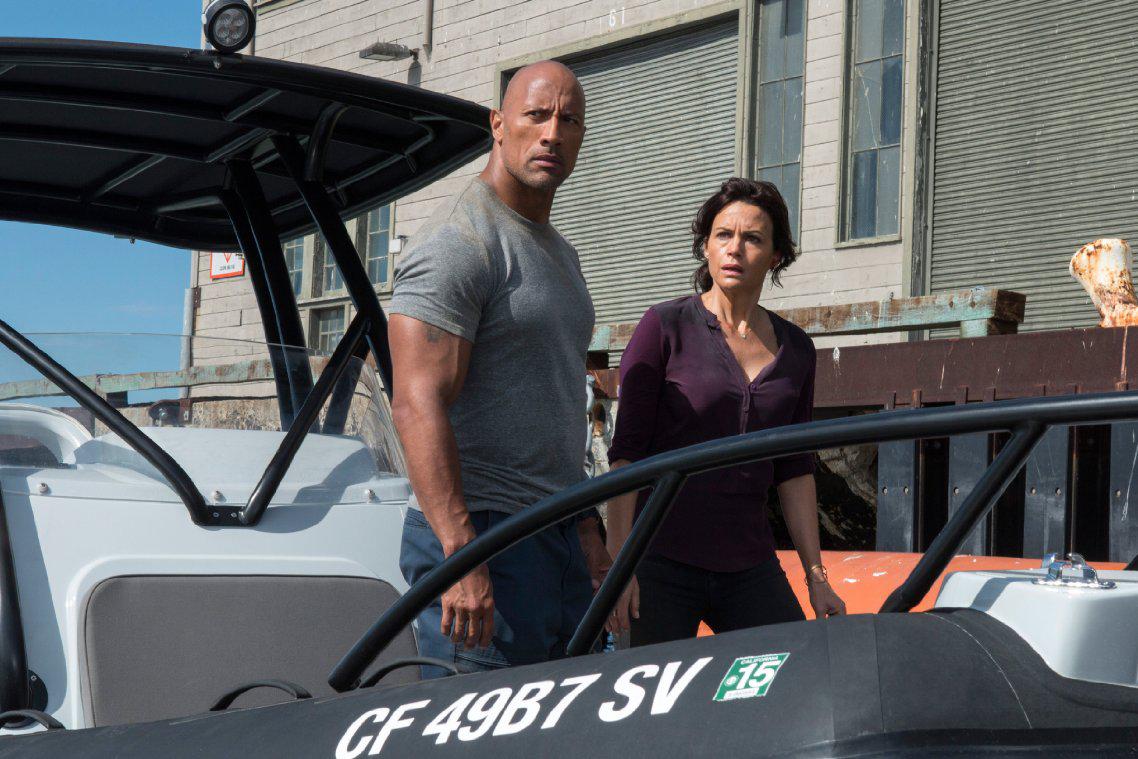

San Andreas purports to be the disaster movie of the year—but, at its core, it’s really a story about a broken family figuring out how to put itself back together. Amid earthquakes, tsunamis, and collapsing buildings, Dwayne Johnson’s and Carla Gugino’s characters, who are in the midst of a tough divorce, are finally able to communicate and eventually reunite. Despite the fact Gugino had just agreed to move in with another man.

But this shouldn’t come as much of a surprise. The estranged couple is a long-standing staple of disaster movies. Something about the end of life as we know it seems to bring everything to the surface, and to trigger a change of heart. Films that focus on catastrophes are chock-full of marriages gone wrong, relationships that can only be repaired by some intense, brink-of-civilization-collapse kind of eros/thanatos fusion.

Take 2012, in which John Cusack and Amanda Peet are reunited after a very brief nod to their prior marital disputes. All it takes, it seems, is the foretold Mayan apocalypse, followed shortly by the disposal of Peet’s second husband. In Twister, Bill Paxton visits Helen Hunt just to get her to sign the divorce papers—but that’s when the storm hits. They only come to understand that they still have feelings for each other once they’ve braved an F5 tornado together, strapped to irrigation pipes.

The Day After Tomorrow, Outbreak—the list goes on and on. If there’s a hero struggling against overwhelming natural disaster, there’s a pretty good chance that he’s been married before, that he and his ex will be thrown together by the vicissitudes of the end-times—and, just as soon as the smoke clears, that they’ll kiss feverishly or stare meaningfully into each other’s eyes, realizing all that they nearly lost.

The trope is especially useful in science fiction, where an apocalypse often offers a pivotal plot point, much like in a disaster film. In The Abyss, Ed Harris and Mary Elizabeth Mastrantonio play an estranged husband and wife whose work brings them together again under the sea, where they must actually go through death and back into life together in order to reconcile. And in Independence Day, Jeff Goldblum needs the help of his estranged wife, the White House press secretary, in order to inform the president of the danger the aliens represent. (Nota bene: Roland Emmerich, who directed Independence Day, also helmed The Day After Tomorrow and 2012. He may be the lead purveyor of disaster-cum-remarriage plotlines.) In all cases, it’s only through crisis on a gigantic scale that the separated lovers are able to repair their relationship.

When you think about it, the disaster reconciliation serves a lot of purposes in a plot. It provides easy character development: The relationship between two leads is established right off the bat, and we don’t need to waste much time setting up their romantic potential. If anything, their incompatibility can be demonstrated very quickly, then thrown away as needed later in the film. The trope also requires having (supposedly) mature adult characters, who have depths of life experience that may make us trust them or sympathize with them all the more. Really, the reconciliation of an estranged couple can provide all of the emotional engagement a viewer needs, while the rest of the film is a nonstop adrenaline rush with almost zero emotional content. And at the end of the movie, once every skyscraper has collapsed and a giant wave has overturned at least one cruise ship, the reconciliation trope adds some much-needed complexity to a happily-ever-after ending. We know that yes, these two will be together going forward, but it will be in a world that looks (almost) entirely different from our own.

The trope of remarriage as plot propeller has an even older heritage. Many screwball comedies of the 1930s and 1940s center on an estranged couple who either reunite after a separation or make amends just before getting divorced. In His Girl Friday, for example, journalist Hildy Johnson asks her old boss/husband for a divorce so she can marry her new love, only to get caught up in reporting a story that ultimately brings her back to her husband, no divorce papers signed. The philosopher Stanley Cavell coined a term for these in his 1981 study, Pursuits of Happiness: the “comedy of remarriage.” Such comedies provide plenty of opportunity for a winning pair to struggle against each other—all while the viewer can see that they’re just so perfect for each other that they couldn’t possibly not end up together.

But disaster films like San Andreas give marriage higher stakes—it’s subject to larger environmental (not social) forces that are able to bring people together or pull them apart. Agency isn’t demonstrated through devotion or commitment, but rather through a simple binary of life-or-death choices. When everything gets primal—and you’re maybe the last two people on earth—there’s not so much consideration of whether he left the toilet seat up or was too focused on his career. It’s worth noting that these flattened gender roles strike at women far worse than men. Disaster movies are highly sexually retrograde when compared to the comedies of remarriage, which foregrounded female agency even when they’re caught in the gender politics of the times. Films like San Andreas are ultimately about a male hero, and while they often give the heroine her own career, a modicum of skill, and independent needs, she still functions primarily as an asset to the ultimate goal: the restabilization of the family unit.

What the disaster-reconciliation plot does share with the comedies of remarriage is a reliance on returning to the social order. A film like The Philadelphia Story is thrilling for its wit, speed, and grace. But it’s remarkable for just how much it reaffirms class divides. Jimmy Stewart’s working-class writer, Macaulay Connor, is a crucial plot device for shedding light on the problems and the iniquities of the elite; but in the end, Tracy has to be with C. K. Dexter Haven, if only because they are of the same class. In the disaster film, society as we know it may be wiped out, but by concluding with remarriage, the movie reasserts familiar social values.

The remarriage structure offers some easy moral comfort and reassurance amid a world gone wrong. As we watch the cities crumble and the human race get vaporized, it helps to see that we still have some hope—likely in the form of one couple who just might rebuild everything, be it literally or figuratively. This provides a comfort that’s both romantic and parental, and helps us believe in renewal. And when you have a crevasse the width of a semi-truck running across a California highway, that’s especially valuable.