Read all Slate’s coverage of The Jinx.

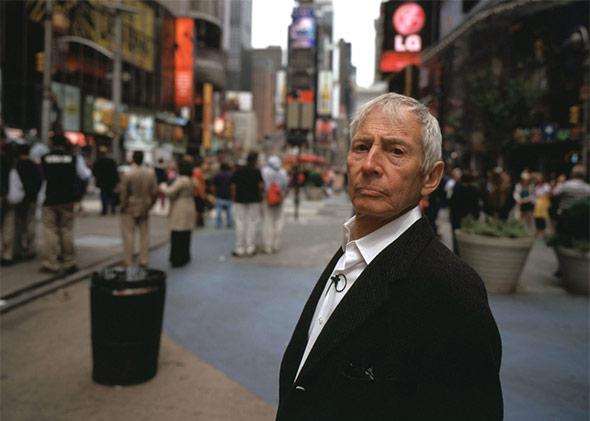

If the eyes are the windows of the soul, Robert Durst’s soul is inscrutable. His eyes are black and beady, hidden behind constantly blinking lids, like a shark with a tic. Durst, the (now-elderly) scion of a New York real estate family, is the unlikely star of HBO’s The Jinx, the true-crime docuseries set to air its final episode this Sunday. Down to its title, the supernatural figures heavily in The Jinx, which focuses on Durst’s involvement in three murders in three states over three decades. Even the show’s name begs the question: Is Durst the luckiest man alive for getting away with three murders, or the unluckiest for finding himself connected to so many gruesome crimes?

The Jinx director Andrew Jarecki got unprecedented access to Durst, who has been reluctant to sit for interviews in the past. The show’s layered narrative structure introduces a recurring cast of characters whose lives or careers have overlapped with Durst at some point. One such character is Cody Cazalas, a big guy with a gray mustache who was the lead investigator in the Morris Black case. This case began with the discovery of a man’s torso floating in Galveston Bay. Several garbage bags were found floating nearby, bags containing arms and legs that had been expertly detached from their owner. Black’s murder—dubbed accidental in a struggle over a gun with Durst—left a deep imprint on Cazalas. Galveston isn’t Mayberry, but it also isn’t Capone’s Chicago. And it’s Cazalas who delivers what may be the docuseries’ most interesting line.

In Episode 4, we watch the judge pronounce Durst not guilty. Durst cuts a sympathetic figure, blinking in disbelief and asking his attorney if he heard correctly. The attorney nods. Then an emotional Cazalas appears on the screen, red-eyed but steady: “As a homicide investigator,” he says, “you work for God. Because the victim isn’t there to tell his story. You’re there to represent the victim, you’re there to tell his story, you’re doing that for God.”

It brings to mind a passage from the New Testament book of Colossians, in which the apostle Paul tells believers to do their work, whatever it may be, as if they were doing it for God. Cazalas, clearly feeling the weight of his burden, starts to say that he feels like he let someone down—but is overcome by emotion and asks to stop filming.

This conundrum is at the heart of The Jinx: Who speaks for the victims now that they can’t speak for themselves? Is it Durst? The detectives? The victim’s family and friends who have been left behind to grieve? One of the strongest tenets of religion is the belief in essential human dignity. That dignity is taken irrevocably in murder, and in Cazalas’s view, he is responsible for righting the wrongs done to the degree that he—or anyone—can. As a homicide investigator, Cazalas says he answers ultimately to God in the pursuit of truth and justice.

The question of religion in law enforcement spans millennia. The apostle Paul’s letter to the Romans, written in 55-ish AD, contains this reminder: “Therefore whoever resists authority resists what God has appointed, and those who resist will incur judgment. For rulers are not a terror to good conduct, but to bad.” Christians have taken this to mean that government is this good gift from God and that only evil men need live in fear of the authorities. We’ve seen enough to know this isn’t always true—one doesn’t have to look far for examples of law enforcement doing evil—but this is the bridge on which law enforcement and religion meet.

Morris Black was not, by any accounts, a saint. Acquaintances in Galveston described him as intentionally provocative, saying “He’d push you to where you’d want to kill him.” The Jinx suggests that Durst may have killed Black because Black knew too much about his life back in New York. Durst admitted to cutting Black’s body up in a particularly memorable turn of phrase: “I did not kill my best friend. I did dismember him.”

Over the course of the series, Cazalas becomes a stand-in of sorts for the viewers convinced of Durst’s guilt. He is chasing a conviction that may never come, and the injustice of it all moves him to tears. Durst may never end up behind bars, and Cazalas mourns that fact not because he may kill again—he is frail and 71 and very aware of the cloud of suspicion around him—but because Cazalas feels an acute sense of failure on behalf of the victim. Part of The Jinx’s success lies in its timeliness. Not only has it been compared to “Serial” for television, but it also indicts the American criminal justice system at a time when a full third of Americans believe the police lie routinely on the job. That the criminal justice system has not yet put Durst behind bars seems like sheer incompetence, at best. Cazalas knows that.

There is perhaps no one more committed to bringing Robert Durst to justice than Cody Cazalas, and perhaps he will see that day, given that the Susan Berman case has been reopened. But short of playing God, there’s only so much he can do, and only so many questions that can be answered this side of paradise.