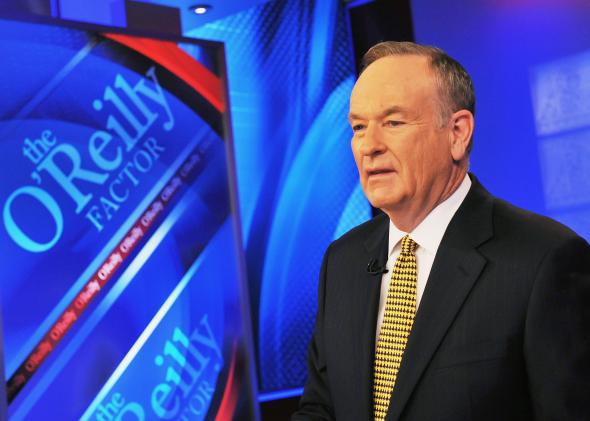

Kennedy’s Last Days, Bill O’Reilly’s illustrated 2013 book for young readers about the JFK assassination, has emerged from retirement. Written for 10- to 18-year-olds, it might have remained harmlessly out to pasture, emitting the occasional flatus of patriotism or self-aggrandizement, had its author not been accused of fabricating part of its epilogue. In the book’s final pages, O’Reilly describes how he, then a young and intrepid TV reporter, tracked down a shadowy associate of Lee Harvey Oswald’s in Florida. The Russian-American businessman George de Mohrenschildt had known Oswald’s wife Marina, and helped Lee get his first job in Dallas. “As I knocked on the door,” O’Reilly writes, “I heard a shotgun blast. He [Mohrenschildt] had killed himself.” But now news outlets are challenging that narrative with reports that O’Reilly was in Texas at the time of Mohrenschildt’s suicide. Said Byron Harris, a former anchor at WFAA-TV: “He stole that article out of the newspaper. I guarantee Channel 8 didn’t send him to Florida to do that story because it was a newspaper story. It was broken by the Dallas Morning News.”

Well! If you missed Kennedy’s Last Days the first time, this is not the most auspicious introduction to a text that bills itself, somewhat defensively, as “completely a work of nonfiction. It’s all true. The actions of each individual and the events that took place really happened.” On the other hand, the book—mostly present tense, told in short chapters that meld charged moments from the lives of its main characters into a dramatic crescendo—doesn’t feel like the kind of document you’d consult for absolute accuracy. It’s a classic feat of O’Reilly storytelling, spiked with his curious blindness about what exactly it is he’s up to. He may think he’s delivering parcels of correct history. Yet his perceptions of reality are so shaded by an obsession with image and reputation, his whole worldview so fundamentally theatrical, that you almost can’t fault him for confusing good stories with true ones.

Papa Bear deserves his reputation as an entertainer. Kennedy’s Last Days, riveting and shameless, gleefully pursues immediacy at the cost of taste. There’s a cheesy reliance on meanwhile, back at the ranch transitions. We meet JFK, rising star, and then his nemesis: “About 4,500 miles away, in the Soviet city of Minsk, an American who did not vote for John F. Kennedy is fed up.” Sometimes these devices make you squirm. “Another event … jump-starts John Kennedy’s journey to the Oval Office,” O’Reilly writes. “Kennedy’s older brother, Joe, is not as lucky as John at cheating death.” If that doesn’t seem like the most sensitive/adept way to introduce the tragedy of Joe Kennedy’s plane crash, at least it outclasses the sensational description of the assassination itself. On a single page, there is “explodes,” “slices,” “knocked,” and “exploding.” Then: “Brains, blood, and bone fragments shower the first lady’s face and clothes. The matter sprays as far forward as the limousine’s windshield.”

Yikes. But some of the stage effects are less offensive, and more head-slappingly fun. A daftly disarming account of JFK’s heroism after a Japanese destroyer ploughs into his WWII boat has the young lieutenant stranded on an island, “choking down live snails and licking the moisture off leaves.” You see, he and his men had to evacuate their ship because “remaining with the wreckage meant either certain capture by Japanese troops or death by shark attack.” (The 1940s axis of evil: Germany, Japan, sharks!)

O’Reilly has a knack for simplifying or blurring historical details without exactly falsifying them. He just…makes them fit his overarching design. And so we learn that the athletic Kennedy swam for Harvard, but not that the president’s coaches remember him as “frail” and “mediocre.” An aura of accuracy emerges from an onslaught of numbers: JFK “naps for exactly 45 minutes” every day; he “can read and understand 1,200 words per minute”; his presidential limousine boasts “three rows of seats” and a 54-year-old driver. The book, its trivia bobbing around in a soup of assumptions, is disingenuously crafted as if readers care how many heads of state attended JFK’s funeral.

These scraps of data attempt to conceal O’Reilly’s biases, which list toward Great Man theories of history and cartoonish notions about fate, good, and evil. (No dice. Nor, for that matter, does O’Reilly’s “helpful teacher” voice—“The Secret Service’s job is to protect the president”—make him seem less grandiose or self-regarding.) Other feints at fair-and- balanced are so laughable they backfire. “Oswald finds strength in the ideals of communism. He believes that the profit from everybody’s work should be shared equally by all,” O’Reilly intones piously. (Look at him being all generous about socialism!) An extravagant hagiography of Birmingham’s Civil Rights marchers is equally crazy-making. (Now he’s bravely, patiently explaining that segregation is wrong! What a guy.)

But slamming O’Reilly for O’Reilly-osity surely misses the point. It’s more interesting to mine the characterization of Kennedy and his assassin for insight into what the author might value and fear. O’Reilly’s president is two things: a Hero and a Performer. As both, he is admired, beloved. Oswald is his opposite—the Envious Nobody. There goes LHO, “unhappy that his return to the United States has not attracted widespread media attention,” needing “to be noticed and appreciated,” with “little to show for his time on earth.” See his power fantasies and spasms of shame—how he measures “Marina’s cheap dresses” against Jackie O’s glamor. On the other side, Kennedy. Courageous, handsome, anointed, “deadly serious about defending his country at all costs.” He “exudes fearlessness and vigor.” His “greenish-gray eyes” sparkle above a “dazzling smile and a deep tan.” You can feel O’Reilly reaching for both the highest compliment he can give JFK and the cruelest insult he can hurl at Oswald. They are these: Kennedy is Great. Oswald is small. Were the “slightly built drifter” given the opportunity, you could almost imagine him lying about his reportage on Fox News.

And that is another star of Kennedy’s Last Days: the idiot box. O’Reilly keeps returning to John and Jackie’s camera-readiness. He lingers over the aspirational force of their bond, their poise, their clothes and hair. JFK, he notes approvingly, “was our first president who liked to be on television.” In Camelot (as on The O’Reilly Factor?) image-consciousness counts as a virtue. Communicators are champions. There is a strange passage where O’Reilly unfolds the origins of Kennedy’s commitment to racial integration; the literary curtain rises on the president as he encounters a newspaper photo of a Birmingham police officer siccing his dog on a student protestor:

Just one look, and JFK instinctively knows that America and the world will be outraged by Hudson’s image. Civil rights are sure to be a major issue of the 1964 presidential election. And Kennedy now understands he can no longer be a passive observer … he must take a stand … he makes a point of telling reporters that the picture is ‘sick’ and ‘shameful.’”

Is O’Reilly subtly critiquing Kennedy here? Implying that his morals are up for grabs, or only accessible through his eyeballs? I don’t think so. Sick and shameful are among the news anchor’s favorite words. Here is what he wants his young readers to admire: the president’s knack for self-mythology, his ability to spur change by presenting an inspirational face to the world. And, Papa Bear takes care to remind us, JFK is not the only crusader to hang his dreams on stage presence and the gift of gab. “If I see injustice, I say something,” he writes in his epilogue, right after the Mohrenschildt passage. Of course he does. He should run for office.