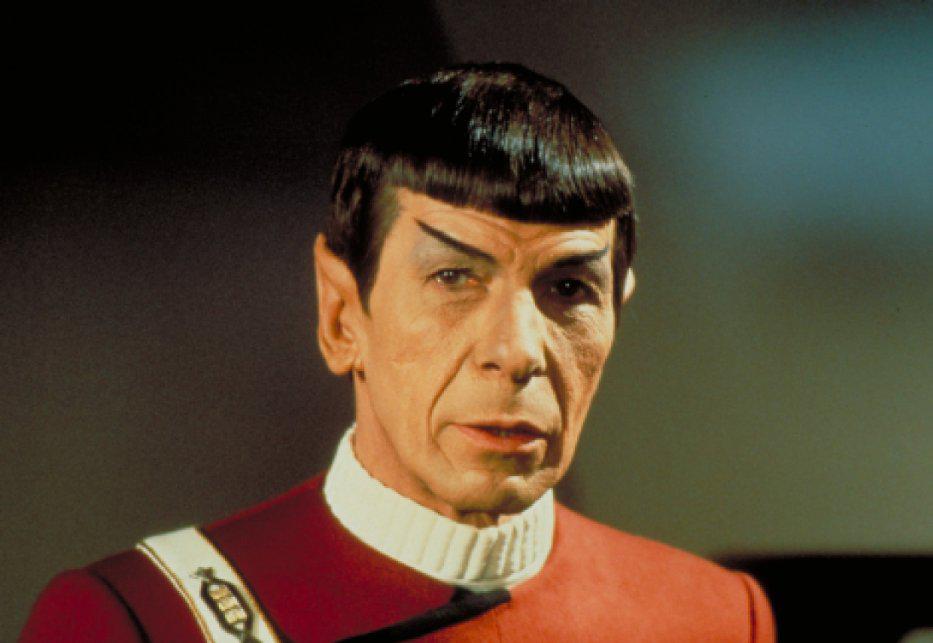

“It hasn’t been easy on Spock,” the half-breed scientist’s mother tells Captain Kirk in the 1967 Star Trek episode “Journey to Babel”: “Neither human nor Vulcan … at home nowhere except Starfleet.” Being Spock wasn’t easy on Leonard Nimoy, either—for much of his career, the actor, like his character, was trapped between two worlds and never quite comfortable in either. And as a lifelong Star Trek fan, I’ve often felt that way, too.

By the time Star Trek was in its second season, the Boston-born theater actor with a Method background was already imprisoned in a gilded science-fiction cage. At 36, after more than a decade of acting and teaching, Nimoy was suddenly the breakout star of NBC’s hit show, receiving more fan mail than the rest of the cast combined. Meanwhile the “official” star of the series, William Shatner, resented that he was not the center of attention, famously counting lines of dialogue to ensure that Spock didn’t get more screen time than Captain Kirk. But it made no difference: Spock was the show’s lightning rod, even though the actor who played him viewed the character and its cultish impedimenta as a detour in a more serious career that was permanently forestalled.

When the series’ original run ended in cancellation in 1969, Nimoy was professionally stranded, along with the other Star Trek actors. Throughout their subsequent decade in the wilderness, they tried (to various degrees) to move on, but mostly couldn’t. Instead, they were reduced to voicing their characters for the crudely-animated Filmation Star Trek, in which leftover scripts from the canceled show found a strange, cartoon half-life. Nimoy, in particular, was fixed in place, permanently typecast thanks to, in Shatner’s words, “the catchphrases and stilted mannerisms” of a character he could no longer play.

And the decade of Star Trek’s purgatory was just as hard for us: the diehard fans who grew up in the 1970s. The show was long gone, apparently never to return, and all we had were the syndicated nightly reruns—the same 79 episodes over and over—and the immense social stigma that sci-fi and nerd-dom carried (of which the Star Trek characters, out in the vulgate, served as cruel, parodistic symbols). We persisted as best we could, since the rewards were so vast and unique. My father, who wanted me to abandon my comic books and spaceship models and do my homework, still grudgingly reminded me when it was time to turn on the black-and-white TV every weekday at six and escape from my mundane reality to spend a joyous hour voyaging across the galaxy with the Enterprise crew.

I was comforted by the discovery that Mr. Spock himself had similar parental problems: His own father wanted him to “join the Vulcan Science Academy” rather than indulge his interest in space travel. Spock, like me, was trying to escape from a world that didn’t seem to like or understand him. (We preteen pioneer Trekkers discovered each other like disguised Christians in the Roman Empire: I remember a nature walk detour at summer camp that led me and another boy into a cloud of bees—seeing his sudden contortions before I was stung myself, I shyly told him that I felt like we were two red-shirts on Star Trek who had wandered into a lethal force field. “Oh, do you watch that show?” he answered, delighted.)

Outsiders and non-believers saw only the show’s cheap production values or overcooked performances—they didn’t understand the urgency with which our imaginations worked to fill in the blanks. The stacks of Star Trek paperbacks we all bought (along with the plastic phasers and the Star Trek comic books and the Enterprise model kits with the engines that nobody could affix properly) had glorious oil paintings on their covers that depicted the Trek universe with baroque realism that far surpassed the cheap effects of the show. And, inside those books, paycheck-seeking mid-level sci-fi writers like James Blish and Alan Dean Foster (the undisputed master of pre-home-video sci-fi novelizations)—as well as the first wave of (mostly female) fan-fiction authors— imbued Kirk and Spock and their shipmates with nuance and depth and inner lives far more vivid than anything available over the airwaves. I remember in particular Foster’s brutal retelling of an abandoned script by Star Trek story editor Dorothy Fontana (resurrected for the animated version of Trek) that focused on the flashback story of Spock’s merciless ridicule by cruel Vulcan children—and how the young half-breed bravely swallowed his shame at being an outcast. It made me feel so much better. If Spock could take it, I thought, so can I.

By the late 1970s, as the Star Trek conventions were starting up (I went to one at the New York Hilton in 1976 and outraged my father by spending $5 on a two-inch plastic Enterprise), Nimoy appeared on The Mike Douglas Show to promote a new TV movie and was, instead, made to answer questions about Spock. When he gravely explained how Vulcans “return home to spawn” every seven years, Douglas and the audience laughed, and I was furious. Nimoy was bravely running toward Spock, rather than away from him, and doing it with the dignity and intelligence that we remembered—but still being ridiculed by the “straights”! This was around the time Nimoy published I Am Not Spock, his famously futile gesture of escape that’s often recalled alongside his novelty song about Bilbo Baggins.

But there was no way out, since by that time the culture had caught up with us: the first NASA space shuttle was named “Enterprise” (with Roddenberry, Nimoy, and others in attendance at the christening). And—along with video games, digital watches and personal computers—the world had discovered George Lucas’s “galaxy far, far away,” paving the way for Star Trek’s triumphant big-screen renaissance in 1979. Finally, Star Trek had a real budget and real special effects, so we could see onscreen what we’d only glimpsed on those paperback covers.

But the first Star Trek movie—in which returning producer Roddenberry was apparently trying to be Stanley Kubrick but ended up as a bargain-rate Arthur C. Clarke—was a misfire, and Nimoy had finally had enough: He insisted that the character be killed. So Spock’s most famous, heartbreaking, iconic scene, his noble death at the end of Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan (1982), was the direct result of the actor’s flagging stamina in the face of the decades-long burden of being Spock. He had become a symbol to be laughed at by the Mike Douglas types, just as young Spock was ridiculed by the more serious Vulcan children. In real life, the needs of the one prevailed.

The expensive cinematic gloss turned out to be beside the point. Lucas introduced unprecedented space-opera spectacle, and the Hollywood sci-fi watershed ushered in stylish cyberpunk from Ridley Scott and apocalyptic thrillers from James Cameron and the Wachowskis. But Star Trek was always different. From the beginning, the inadequacy of the cardboard sets and rubber masks and colored-gel-lit cycloramas of alien sky were irrelevant next to the characters, the writing and the acting, and the fiercely utopian ideology. Spock returned, of course (since Roddenberry, unlike Lucas, could be replaced, which got the movies back on track), and, by 1986, he had resolved his father issues (as had I, more or less), “As I recall, I opposed your enlistment in Starfleet,” Ambassador Sarek told his resurrected son at the end of (the Nimoy-directed) Star Trek IV: The Voyage Home. “It is possible that judgment was incorrect…your associates are people of good character.” Sarek might have been speaking to any of us—not just Spock, or Nimoy, but anyone who has ever pursued a socially-unacceptable goal in the fervent belief that they would, someday, be appreciated. I Am Spock—the book Nimoy published in 1995—signaled his acquiescence to what Spock might have called his “first, best destiny.”

Which brings us to a Friday morning in 2015—a year that still sounds to my inner, sci-fi-obsessed, 10-year-old self like the far future—when a flurry of texts and tweets on our Star Trek–like cellphones spread the news of Nimoy’s passing and the President of the United States himself (about whom Vulcan comparisons have been made, both kindly and unkindly) delivered a memorial statement, indicating how far we’ve all come in the half-century since the Vietnam era when the Starship Enterprise and its mixed-gender, interracial crew first appeared on TV screens.

Yes, we’re all carrying “communicators” now, but as Roddenberry’s characters understood, it’s not the technology that must evolve, it’s the people: the tolerance, the openness, the inclusiveness that Spock stood for (“Infinite Diversity in Infinite Combination,” according to the Vulcan credo) that are the keys to the future. Across the long decades, through his on-again, off-again rejection and embrace of his famous alter ego, Leonard Nimoy understood what it meant to be on the vanguard and pay the price—to do something strange and stick to it until it becomes mainstream and accepted, and to do it fearlessly. Roddenberry distilled that idealism in his original conception of Star Trek, but Nimoy lived it. He showed how anyone could withstand the pain of being ostracized for being different—and why it was always worth it, since the future so often vindicates and rewards those misunderstood in their own time.