Film composers occupy an awkward place in the cultural imagination. They are, broadly speaking, creators of art music (by which I mean orchestral, chamber, or electronic music drawing on the “classical” tradition), and so enjoy some of the Romantic genius mystique afforded by that genre. However, they are also applied artists, workmen-for-hire whose creativity is harnessed specifically for the benefit of a separate, non-musical product over which they have only minor control. I say this not to denigrate the work of film composition (quite the opposite), but only to explain why appraising something like the Oscar category for Best Original Score can be so difficult: Any consideration of the music as music must be tempered with how the score functions in the movie for which it was made.

The Academy advises voters to evaluate a score’s worth based on its “effectiveness, craftsmanship, creative substance and relevance to the dramatic whole, and only as presented within the motion picture.” In this year’s Brow Beat ranking of the nominees—a fine and varied cohort—I’ll take all these criteria into account. But I’m going to favor those scores that manage to do their jobs while also transcending that subservient role to stand alone as a complete musical statement. Writing an emotionally or narratively effective tune for a movie is a skill; but it’s doing that while simultaneously creating music that expresses the unique sensibility of the composer that is a true, award-worthy art.

And so, ranked below in order of fine to fantastic, are this year’s nominees.

5. The Theory of Everything - Jóhann Jóhannsson

Jóhannsson, a first-time nominee, has a job to do in this film—the surprisingly honest portrait of the romance between the theoretical physicist Stephen Hawking and his first wife, Jane—and he does it well. The writing manages to be both delicate and lush, shifting through moods of sweet romance, anxiety, and the thrill of inspiration with efficiency and wit. The passages that focus more on texture than melody are particularly sparkling, drawing on a charming palette of piano, celeste, strings, harp, and light winds, and a harmonic vocabulary that will appeal to fans of Philip Glass. Taken as a whole, however, Jóhannsson’s score is very familiar—especially in the moments when he is called upon to convey the “wonder of science” and he responds by dusting off some predictable arpeggios. The dependence on certain stock sounds (however luminously rendered), combined with the film’s heavy dependence on preexisting music (Wagner, jazz bands), places Everything last on my list.

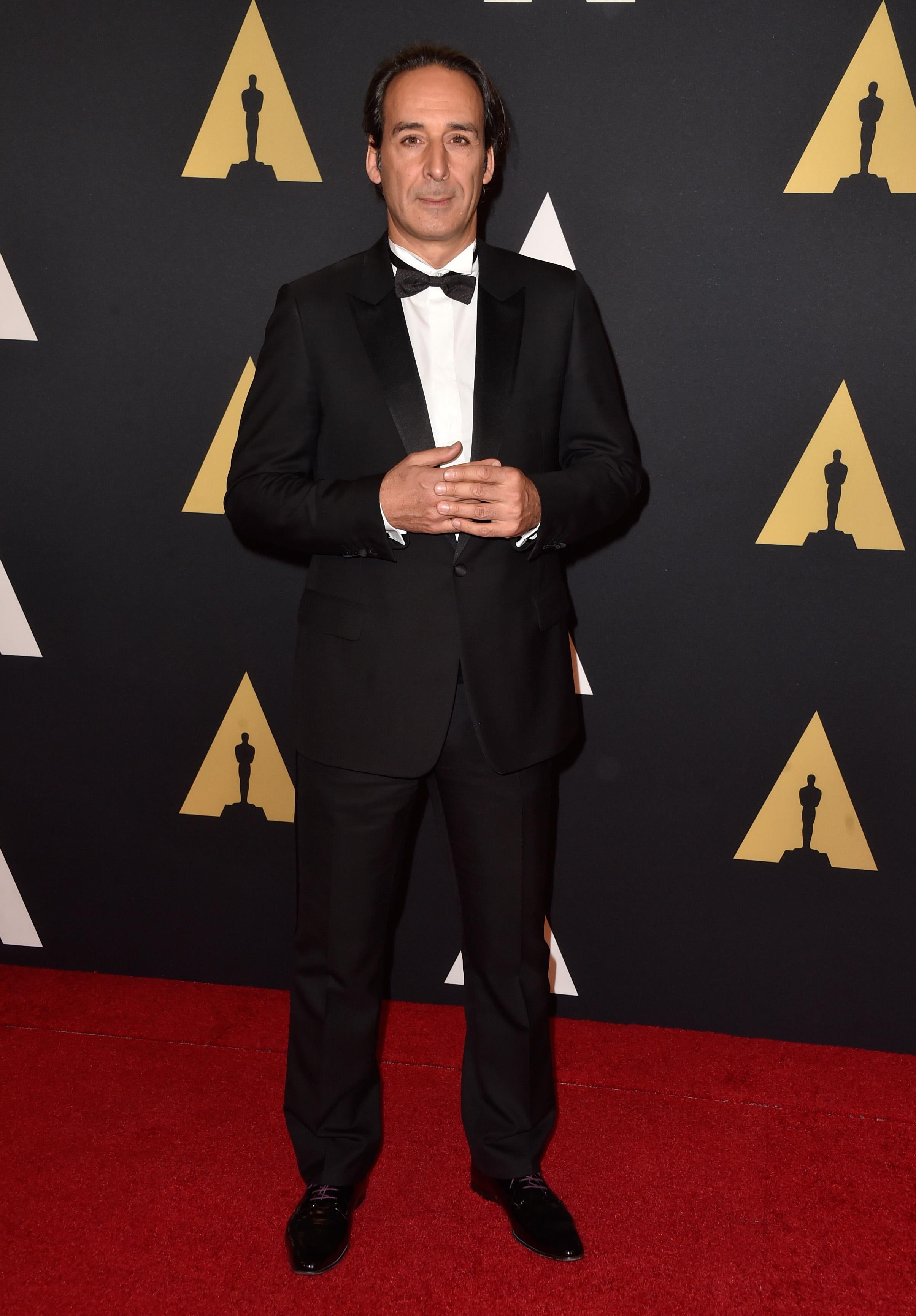

4. The Imitation Game - Alexandre Desplat

Desplat is one of the powerhouses on the contemporary film scoring scene, so it’s no surprise that the Academy has honored him with two nominations this year (giving him eight in total, so far with no wins). His score for the Alan Turing biopic is clearly the weaker of the two—but with good reason: At a screening of the film in New York last fall, I heard director Morten Tyldum reveal that Desplat composed the score in just two weeks, between other projects. Desplat is skilled enough that the music—defined mainly by wary melodies dancing manically over ominous undercurrents, and one sweeping, melancholy theme for Turing—doesn’t sound rushed, but it does strike me as more of a highly competent first draft than a fully explored musical world. That said, the composer’s grooving rhythmic game is delightful as ever here, and the occasional, Chopin-like piano interludes are lovely. It’s worth a listen, but not the award.

3. Mr. Turner - Gary Yershon

Yershon, another first-timer at the Oscars, has produced the most inventive music of all the nominees for this film, a portrait of the life of the English painter J.M.W. Turner. The trouble is, there isn’t enough of it in the movie to justify the prize—as with Theory of Everything, period music takes up a lot of space. But what’s there is beautiful, couched in a tonal language that resembles early Schoenberg—thick, slippery, and bittersweet, like the taste of absinthe. Winds dominate the sumptuous chamber sound, with especially striking contributions by the saxophones and the clarinet. As much as I gravitate toward it, too much of contemporary film music relies on the same romantic minimalism favored by Desplat, Zimmer, and others; though his is not the best score in his class, Yershon offers a welcome reminder that there are other, equally compelling sounds out there as well.

2. Interstellar - Hans Zimmer

What else can I say about Zimmer’s gothic masterpiece that I haven’t already? Despite multiple nominations, the composer hasn’t taken home an Oscar since he won for The Lion King in 1995, and the media campaign for this score in 2014 would suggest that he’s looking to correct that this year. Given the gloriously maximalist theatrics on display—all informed by science—in Zimmer’s accompaniment to Christopher Nolan’s jaunt through the universe, another win would not be unwarranted. Though the pipe organ-fueled music threatened to blow out the speakers in unprepared theaters, it also was fabulously transporting—exactly what a space odyssey requires. But more impressive, Zimmer’s work, somehow simultaneously magisterial and humane, continues to move me long after the associated images have faded. The only demerit I can render is that the score is more-or-less uniform in a tone—a sort of trembling awe—that can become exhausting in large doses. The best scores iterate their material through different moods; for a master-class in that, look to my first-place pick.

1. The Grand Budapest Hotel - Alexandre Desplat

Regardless of whether you care for Wes Anderson’s brand of highly stylized auteurist storytelling, Desplat’s work on Grand Budapest is beyond reproach. To conjure up the sound of Anderson’s Republic of Zubrowka, he casts himself as something of a Bartókian composer/ethnomusicologist, except that the culture he draws on for his “folk” themes isn’t real at all. In other words, Desplat has achieved the remarkable feat of imagining an entire folk music that echoes the alpine European locale in which it is set, but that remains unique as well. Fittingly for an Anderson film, Desplat’s writing is also playful and charming, leavened by liberal use of pizzicato and tremolo in the strings and a light brush touch on the drum set. And folk instruments like the cimbalom and zither lend a certain faux “ethnic authenticity” alongside wry use of the organ and timpani. Colorful orchestrations aside, Desplat is masterful here at transforming simple themes—especially a jangly jig refrain and a swerving seven-note see-saw motif—through a wide array of moods, ranging from mysterious to martial, regal to funereal. All-in-all, Desplat’s Budapest score is both a completely realized musical world and the perfect complement to its movie: a true achievement in the art of film composing. And for that reason, when the winner of this golden statuette is revealed on Sunday night, it better be Desplat—any other outcome would be a scandal.