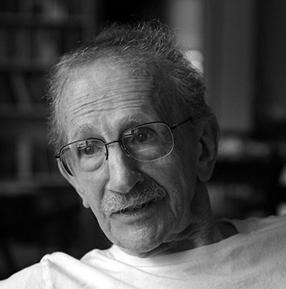

The following excerpt is from the Library of Congress’s transcription of Philip Levine’s speech, which took place on May 3, 2012 and was Levine’s final lecture as Poet Laureate. Reprinted with permission of the Library of Congress and Levine’s estate.

As a somewhat older teenager, 19 to be exact, in the spring of 1947, I attended my first poetry reading. It was held in a small room in Webster Hall of Wayne University and it began at exactly a few minutes after 1 PM. The readers were university students and two faculty members. I had seen an announcement of the event in the school newspaper and my curiosity was aroused. I remember almost nothing of the event except for one line of verse and one fact. The fact: There existed in the school library something called the Miles Poetry Room, which held a significant collection of 20th century poetry. Once the Library of Theodore Miles, an inspiring poet and former faculty member at Wayne who died while serving in the Navy in the Pacific during World War II. The line that I remembered: “When in a mirror, love redeems my eyes.” The opening line of a poem recited by its author, Bernard Strempek. “When in a mirror, love redeems my eyes.”

Bernard Strempek was a tall, loose limbed boy who looked no older than 15. The recitation was in a voice the likes of which I had never heard in all my wanderings through Detroit. How to describe it? A cross between a high tenor version of Cary Grant and the call to arms of a mad warrior in a great human struggle. A John Brown or Joan of Arc voice. Whoever this Strempek was, he was overpoweringly serious about what he regarded as poetry. Why that one line? I was struck by this boy’s willingness to openly acknowledge his narcissism, and I loved the music and movement of the line, the way it began surprisingly and turned to a flow that crashed on the shore of the word love. I had never attempted such mastery of rhythm. In my writing, I was concerned with narrative and imagery. I so worried Strempek’s single line in my head that the rest of that poem and the poems of the other poets passed as noise. I was too shy or too humbled by these brazen poets to attempt to speak to anyone. I went home totally confused by the experience.

The next afternoon I decided to visit this new discovery, the Miles Poetry Room. The room itself was a comfortable one with high windows that looked out on a good deal of auto and truck traffic–but a quiet room nonetheless. On that first occasion, I encountered a single reader whom I immediately recognized as young Strempek. I picked a book up from the shelves–there were literally thousands of books–and pretended to read. Suddenly Strempek turned to me and said, “Listen to this. I’ve discovered a new master.”

He read from a slender collection, “My brother came, the wounded,” and he paused. “What an amazing opening,” he said. “Why didn’t I think of it?”

I was surprised to discover his speaking voice was the same as his formal presentation voice. The same original accent, the same trembling seriousness that seemed to say, “Yes, I am a poet, don’t fool with me.”

“This is a discovery for me,” he said. “You have any brothers?” I did.

“Then this poem was written for you,” and he handed me the book as he rose to leave. “Abel.”

This is the poem he had been reading and I will read to you. “Abel,” by Demetrios Capetanakis, written in English by a Greek.

My brother Cain, the wounded, liked to sit

Brushing my shoulder, by the staring water

Of life, or death, in cinemas half-lit

By scenes of peace that always turned to slaughter

He liked to talk to me. His eager voice

Whispered the puzzle of his bleeding thirst,

Or prayed me not to make my final choice,

Unless we had a chat about it first.

And then he chose the final pain for me.

I do not blame his nature: he’s my brother;

Nor what you call the times: our love was free,

Would be the same at any time; but rather

The ageless ambiguity of things

Which makes our life mean death, our love be hate.

My blood that streams across the bedroom sings:

“I am my brother opening the gate!”

At the time I had no idea this poem would stay with me for the rest of my life, as would the memory of that encounter with this original and generous young man. I called him a boy earlier and he was. He was 16 years old majoring in French, which he spoke fluently. When later I asked him why French I got a one-word answer, Rimbaud, for the boy-genius of French poetry was his idol and the model for his poetry in his life.

…

To answer his question 60 some years later, yes, I have brothers and one is a twin, an identical twin brother, who still resembles me physically and perhaps in other ways, but I don’t think one needs a brother to be struck by the poem “Abel.” In fact, all one needs is an ear to hear it and the knowledge that brother killing brother is one of the oldest and saddest truths of the human mythology and history.

At 19 I had never heard or read a poem that recreated a mythic character’s speech in contemporary English. Not only does “Abel” use the words I might use if I were more fluent and accomplished; he says things I might say, for I also saw those scenes of peace that always turned to slaughter and the feelings of that day or, for that matter, the films of this day. At the time I had recently stumbled into modern and modernist poetry, so the whole question of form was utterly new and confusing to me. So much of what I read was inspiring and incomprehensible that I was both lost and found. Found in that the language of Yeats, Elliott, Pound, Crane, Dylan Thomas was thrilling and lost when I attempted to discern what they were writing about. I had adopted a mantra I had found in Elliott. One understands a poem before one understands a poem. One gets it in the gut and the rational understanding eventually follows.