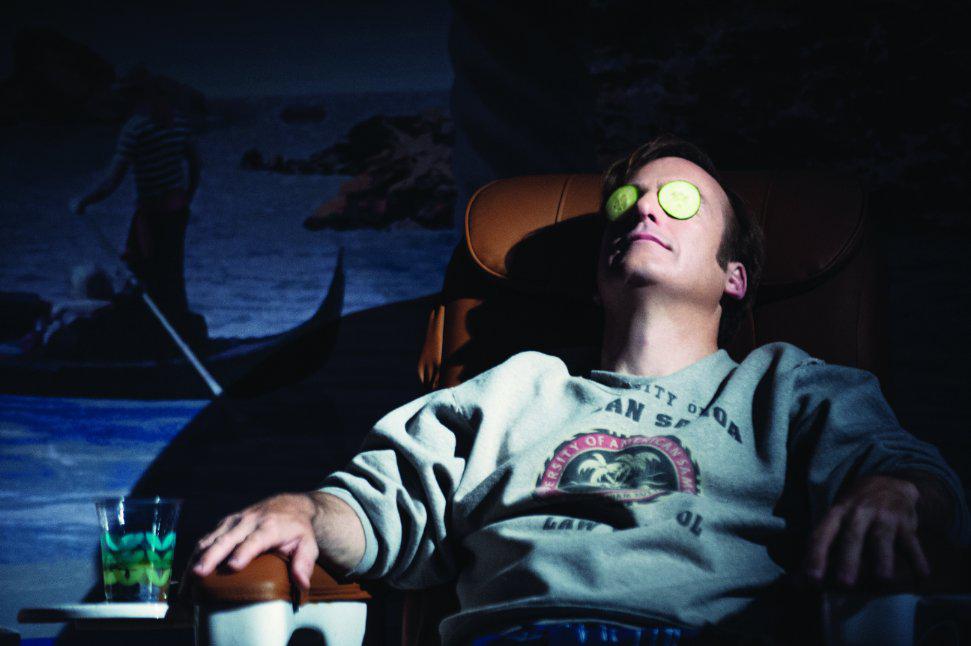

In the opening minutes of Better Call Saul, the Breaking Bad spinoff from AMC that premieres Feb. 8, we’re reintroduced to shady legal mastermind Saul Goodman, whose newly humdrum post-Heisenberg existence recalls Henry Hill’s witness-protection purgatory at the end of Goodfellas. A man whose lifestyle was once louder than his ties has been reduced to mopping the floor at a Cinnabon and consuming copious amounts of liquor alone. But to really hammer home his fall from grace, the show deploys a time-honored “sad life alert” trope: We see Saul watching TV.

These days it seems that whenever TV characters plop down in front of the television, it’s a kind of shorthand for the tedium and misery of their lives. The activity carries a whole host of sad connotations: emptiness, stupidity, loneliness. In Saul’s case, he flips zombie-like through the channels, from QVC to a nature show starring an “African pancake tortoise” to a weatherman warning of an impending snowstorm. (Metaphor alert!) It goes without saying that television, never more central to our cultural conversation, has gained unprecedented respect as a medium. And yet, on TV shows themselves, it still has a remarkably bad rap.

Take Don Draper, who—forced to take a leave of absence by his ad-agency partners in Mad Men—whiles away his unstructured days drinking and gazing at trippy Frank Capra movies. Vince Gilligan is particularly fond of the trope: When Breaking Bad’s Huell finds himself abandoned at a safe house for what could be all eternity, his physical isolation is accentuated by his only company: a small television set.

In comedy, TV-watching is mostly used as a proxy for a particularly American brand of slob-itude. Think of Homer Simpson and family parked in front of the tube, enjoying the rich TV universe of The Simpsons, which runs the gamut from anarchic violence (Itchy and Scratchy) to gleeful inanity (local news anchor Kent Brockman). Or Beavis and Butthead watching an endless loop of MTV videos between ill-fated efforts to “score” in real life. Or Liz Lemon vegging out and snacking on Sabor de Soledad. Or Al Bundy, perhaps the gold standard of American macho slovenliness, whose default position on the couch is hand-down-pants, remote in hand. For a dose of the cerebral, there’s Louie, which, straddling the line between genres, trots out the occasional dadaist, apocalyptic TV news report to emphasize its protagonist’s perpetual bafflement with the world.

Sometimes, things veer away from character development and into media criticism. In season five of CBS’s The Good Wife, Alicia Florrick becomes addicted to a fake show, the lugubrious crime drama Talking at Noon, which is really a not-so-subtle compendium of prestige television cliches—the writers’ way of thumbing their nose at the antihero-laden landscape of cable. After the shocking death of her ex-lover Will Gardner, Alicia binge-watches the series, only to fall further into a funk. It’s about as meta as it gets.

The idiot box-as-metaphor is clearly attractive to TV writers. If you want to show that your character has lost her moral will, or that he is, say, powerless against the caprices of modern capitalism, there’s perhaps no simpler solution than to plunk them in front of a glowing box whose flickering images make an easy stand-in for the absurdity of modern life.

And there may very well be a real-world basis for this, as the drumbeat of studies that reveal a link between binge-watching and a host of undesirable tendencies—depression! anxiety! a complete disconnect from humanity!—keeps getting louder. But needless to say, many of us no longer collapse into armchairs to meander through channels in a glazed stupor; we pick the shows we want to watch, then we stream them. And it’s a shame that the symbolism of TV-watching hasn’t entirely kept pace with the actual, evolving role of TV in our lives—because the streaming era could be fertile ground for writers. Imagine the dramatic possibilities: a slew of unintentionally revealing Netflix recommendations tears a couple apart. A frozen HBO Go screen before a big premiere wreaks emotional havoc on a family. In any event, it seems fair to assume that just as much drama can be wrung from toggling through a Hulu menu as mindlessly fiddling with a remote.