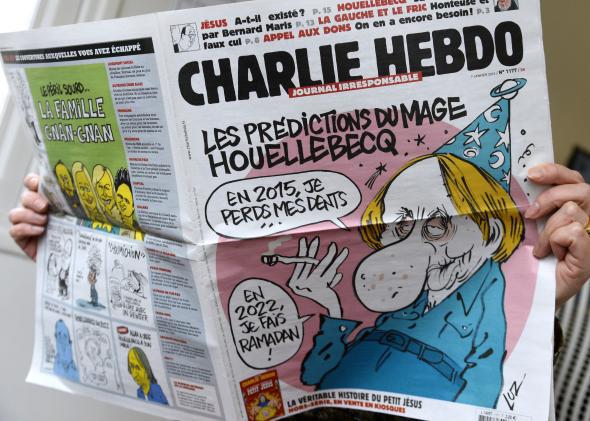

It’s hard to know how to respond to the horrific murders of much of the staff of Charlie Hebdo earlier this week. For the past few days, social media has seen an outpouring of grief and condolences, of cartoon tributes to the controversial magazine, of the #JeSuisCharlie hashtag. But if you felt like you wanted to do something to take a stand against terrorism instead of just emoting on Twitter, some commentators had a suggestion: Subscribe to Charlie Hebdo.

These reactions echoed a sentiment widely shared last month, after theaters began backing out of plans to screen The Interview in light of threats from the group that hacked Sony. “I probably wasn’t even going to see The Interview until theaters started pulling it, but now I will drive as far as necessary to watch it,” tweeted one typical would-be moviegoer, expressing a view that grew in popularity after Sony (temporarily) suspended plans to release the film.

The impulse to support a piece of media that has provoked violence (or threats of violence) is understandable. If you want to stand up for free speech, buying a movie ticket or newspaper that you normally wouldn’t buy seems like a simple, concrete way to take a stand against censorship. Subscribing to Charlie Hebdo might also feel like a satisfying way of thwarting the terrorists and those who share their goal of suppressing the magazine’s influence.

Far be it from me to tell Arnold Schwarzenegger how to respond to this awful attack—if it makes him feel better to subscribe to Charlie Hebdo, great. But I do take issue with the peer pressure contained in his and other tweets encouraging people to subscribe to Charlie Hebdo to take a stand.

This response runs the risk of warping the principle of free speech, which holds that people should get to say stupid, offensive, and otherwise objectionable things regardless of how many other people agree with, endorse, or financially support those ideas. You can decline to purchase Charlie Hebdo on the grounds that its cartoons are racist and inflammatory and simultaneously believe that Charlie Hebdo has the right to publish those cartoons freely and without the threat of violence. Similarly, you can decide not to see The Interview because it just doesn’t look very funny, but still believe that those who make violent threats should not get to determine whether other people can watch The Interview.

If supporting free speech required buying controversial media, First Amendment activists would have to buy every derogatory or just plain idiotic newspaper, book, movie, and painting in existence, which would, of course, be impossible. Supporting free speech means believing that cartoonists should get to draw offensive caricatures without fearing death or imprisonment, even if no one wants to give them money for their work. You may well feel it’s your duty, as a citizen of a free democracy, to stand up for speech rights. But no one should feel it’s their duty to prop up controversial speakers in the marketplace.

Equating support for the right to blaspheme with support for the practice of blasphemy, as Jonathan Chait put it, is vexing for other reasons, too. Not everyone has the financial means to pay for censored art for the sake of making a statement, and a lack of money shouldn’t impede citizens’ ability to participate in the public discourse. Meanwhile, the equation of speech with money, embraced in the Citizens United decision, has given wealthy individuals and corporations an outsized voice in American democracy. If only people with money get to decide which types of controversial speech are worth defending, then the voices of the disadvantaged will continue to be drowned out.

The marketplace is a fine venue for promoting ideas and art that you support and criticizing ideas and art you don’t. We should continue to use the marketplace to support media we find laudable, and boycott media we find despicable. By all means buy a ticket to The Interview if you enjoy Seth Rogen comedies, or subscribe to Charlie Hebdo if you find its cartoons and commentary insightful. Buy the type of media you want to see more of in the world.

But the marketplace is not a good venue for determining which forms of speech ought to be allowed in a democratic society. Speech should be free regardless of how many people want to support it and how much money people are willing to throw at it. The impulse to champion Charlie Hebdo’s right to free expression by reaching for your wallet may be heartfelt, but pause to think of the precedent it sets and message it sends before you pressure others to follow your lead. We should be free to subscribe to media we like, and reject media we don’t like, without feeling as though the future of free expression depends on our purchases.