Read more of Slate’s coverage of the Charlie Hebdo attack.

The largest European gathering of comics professionals and fans, the Festival International de la Bande Dessinée, has taken place at the end of January in the small southwestern French town of Angoulême for 42 years. In contrast to American comic book conventions like Comic Con International in San Diego, which are dominated by celebrity appearances and announcements of forthcoming Hollywood blockbusters, Angoulême still places its emphasis on the cartoonists who come to meet their public. The annual Sunday highlight is the announcement of the new Grand Prix de la ville d’Angoulême, the honorary president of the next Festival, whose career is fêted the following year with a major retrospective. This is the highest recognition that can be afforded a cartoonist in France. Wednesday morning, the 2005 winner of this prize, Georges Wolinski, was one of four cartoonists killed in a terrorist attack in Paris that claimed at least 12 lives.

As Joshua Keating has noted already today, Charlie Hebdo was born out of controversy, and has long engaged with confrontational images of all times. The magazine was resolutely satirical, attacking all comers in the name of humor. France, of course, has a strong tradition of political satire that dates back centuries. Honoré Daumier was imprisoned for six months in 1832 for his depiction of King Louis Philippe as Gargantua, and his later image of the king with the head of a pear is one of the most famous illustrations of the 19th century. Yet it is not only the tradition of satire that is revered in France; it is also cartooning.

Unlike in the United States, where comic strips, comic books, and editorial cartoons are generally regarded as only distantly related wings of the same art form, in France the integration of the three is much closer. Each of the four cartoonists killed today worked not only for Charlie Hebdo, but for other newspapers, and for French comic book publishers. The publishing industry in France is both smaller and more central than it is in the United States. With so many cartoonists living in and around Paris, the overlap between different media are quickly eroded in a context where it can sometimes seem that every working cartoonist knows every other one and works across publishing platforms.

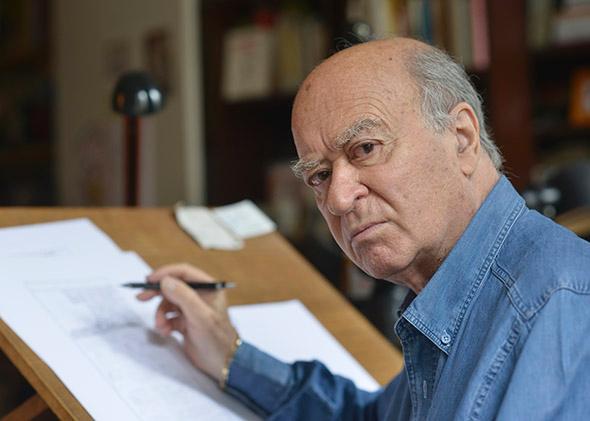

Wolinski’s career was symptomatic: He published comics in the daily newspaper Libération, the weeklies Charlie Hebdo and Paris-Match, and authored, with artist Georges Pichard, the comic book series Paulette. The other three cartoonists slain today, Stephane Charbonnier (Charb), Bernard Verlhac (Tignous), and Jean Cabut (Cabu), had similarly broad profiles. Cabu, one of the founders of Hara-Kiri, the fore-runner of Charlie Hebdo, was the creator of dozens of comic books, including the long-running series Le grand Duduche. In 2006 he drew the cover illustration when Charlie Hebdo ran the Danish Mohammad cartoons. Tignous worked as an illustrator, and he was the author of eight comic books. Charb, who was the magazine’s editor since 2009, authored dozens of left-wing comic books and contributed to the well-known humor magazine Fluide Glacial and the communist daily newspaper, L’Humanité.

It’s a durable myth, especially among American cartoonists, that France is the place where comics are given the respect they rarely get on this side of the Atlantic. While the French comics industry is not without many of the same problems that have beset book publishing around the world, there is some truth to the idea that comics are more central to public life there than they are here; it’s notable that Wolinski was the recipient of the Legion of Honor, and he is not the only cartoonist to have received his country’s highest recognition. France integrated comics into the mainstream publishing industry much earlier than did the United States. Here, the distinction between comic strips and comic books was sharply drawn for most of the twentieth century, and comic books were widely regarded as a disposable form of culture for children. Comics in France—and Belgium—developed differently. Since the most popular newspaper comics—like Hergé’s Tintin—were collected as hardcover children’s books as early as 1930, the medium was viewed as more reputable because it existed as a part of the regular book trade. In France, cartoonists can be genuine cultural celebrites. Cabu, for example, appeared regularly on television chat shows where he drew cartoons while discussing the issues of the day.

The attack on Charlie Hebdo is shocking for its brutality and because it is an assault on the very idea of free expression. Yet the target was not just any newspaper. Today’s attackers seemed to understand the same thing that King Louis Philippe recognized in the 1830s: The visual form of the cartoon makes it viscerally powerful, and central to the French conception of caricature and critique.