Ava DuVernay’s Selma, a retelling of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.’s historic 1965 Freedom Marches from Selma to Montgomery, opens in limited release this Christmas. (The movie will get a wide release on Jan. 9.) Already, the film has been met with critical acclaim: Many, including Slate movie critic Dana Stevens, have named it one of the best movies of 2014. The film has also earned DuVernay a Golden Globe nomination for Best Director—the first ever for a black woman—and nominations for Best Picture and Best Actor.

In her review, Stevens noted the film’s attempt to realistically document the complicated days and months leading up to President Lyndon B. Johnson’s signing of the Voting Rights Act of 1965 “rather than simply re-enact [the movement’s] moments of greatest triumph.” But did DuVernay get it right?

I sifted through archival news coverage, interviews, and public government records to separate what’s fact and what’s fiction. And while the film does, perhaps, exaggerate certain events and relationships for dramatic effect, I found that Selma generally sticks to the historical script. (“Spoilers,” of course, to follow.)

MLK and LBJ’s Relationship

Photo illustration by Slate. Photo by Universal History Archive/Getty Images; Photo by Atsushi Nishijima/Paramount Pictures

The film opens in 1964 in Oslo, Norway, with King (David Oyelowo) delivering his Nobel Prize acceptance speech. We hear rewritten parts of that speech (the King estate did not grant DuVernay permission to use his words) juxtaposed with the 16th Street Baptist Church bombing that killed four young girls in Birmingham. That bombing actually occurred in 1963, the year before King’s Nobel Prize speech, but the overlapping depiction of it in the film sets the stage of racial tension and unrest in the South.

A couple scenes later, the film moves to the White House, where King meets with President Johnson (Tom Wilkinson) to urge him to shift his attention to having Congress pass legislation that will protect voting rights for black Americans—citing the Birmingham church bombing as the kind of racial injustice that will persist if blacks remain unable to register to vote and have a seat on a jury. King and Johnson engage in a tug of war up until the film’s end.

Some critics have taken exception to the testy exchanges between King and Johnson presented in Selma. LBJ historian Mark K. Updegrove, writing for Politico, called the film’s depiction of their relationship a “mischaracterization”: “In truth, the partnership between LBJ and MLK on civil rights is one of the most productive and consequential in American history.” He argues that, based on a recorded phone conversation from Jan. 15, 1965 between the two, LBJ was more than cooperative with MLK’s quest to secure the vote for black Americans and that he even came up with suggestions for a course of action.

Building the Movement

After King’s discouraging first meeting with LBJ, he takes his civil rights movement to Selma, a small city in Alabama that activist Diane Nash (Tessa Thompson) says is where they’ll find “the next great battle.” Many of the activists introduced in this section are based on real historical figures: Many members of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC)—James Bevel (Common), Hosea Williams (Wendell Pierce), Andrew Young (André Holland), Ralph Abernathy (Colman Domingo), and more—were at MLK’s side in Selma and, as we see, used the home of Richie Jean Jackson (Niecy Nash) as a safe house. Amelia Boynton Robinson (Lorraine Toussaint), an early leader of the civil rights movement in Selma, also played a major role in the Freedom Marches, as did John Lewis (Stephan James), a chairman of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC).

Earlier in the film, we see an older woman, Annie Lee Cooper (Oprah Winfrey), denied the right to vote on what DuVernay says was the real-life Cooper’s fifth attempt to register, after she couldn’t name the 67 county judges in Alabama. This was one of the many very real requirements meant to restrict blacks from voting. She, like many Selma residents ignited by MLK’s speeches at the Brown Chapel Church, later joined the movement.

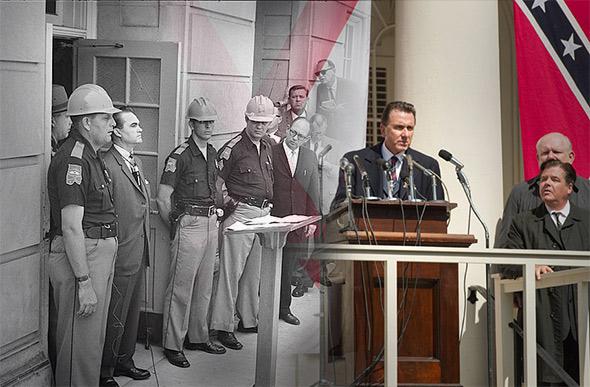

Governor George Wallace and Sheriff Jim Clark

Part of what made Selma, and Alabama as a whole, the perfect “battle ground,” were two of its most vocal public officials, Gov. George Wallace (Tim Roth) and Sheriff Jim Clark (Stan Houston). In the film, King paints Clark as the kind of bigot who could be counted on to incite violence against blacks, which violence could then be used to build sympathy for King’s movement. This matches a description SNCC executive secretary James Forman (Trai Byers) shared in his autobiography—though he and the SCLC, as we see in the film, had some early differences of opinion.

In January 1965, King led more than 100 Selma marchers to the county courthouse as part of a nonviolent demonstration aimed at the office for voter registration. But as we see in the film, the protest came to a head when Cooper, who attended the sit-in, hit Clark after he twisted her arm and eventually dragged her to the ground—the photographs of which were splashed all over the news. Dozens were arrested, including King, just as in the movie.

Photo illustration by Slate. Photo by Warren K. Leffler/Library of Congress; Photo by Curtis Baker/Paramount Pictures

Gov. Wallace, known at the time for being referenced in MLK’s “I Have a Dream” speech and seen as an uncontrollable hothead by LBJ and his advisors, was already a behind-the-scenes tyrant. In the events that followed the protest at the county courthouse, he sanctioned a surge in violence against blacks authorized, at first, by FBI director J. Edgar Hoover (Dylan Baker).

The Death of Jimmie Lee Jackson

The movie faithfully portrays how the next month, in nearby Marion, the SCLC organized a group of protesters to march to the Perry County jail only to meet a wall of state troopers. Just as in the movie, the police killed the streetlights to thwart the onlooking reporters, and all hell broke loose.

One of the protesters, 26-year-old Jimmie Lee Jackson (played in the movie by Keith Stanfeild) was killed in nearby café. According to eyewitness accounts, police troopers stormed the café, attacked Jackson’s grandfather and mother, and then shot Jackson at close range before fleeing. In the film, Jackson appears to die in his mother’s arms shortly after being shot, but he actually died over a week later in the hospital.

James Bonard Fowler, the trooper who shot Jackson would, over 40 years later, claim self-defense in court, saying that he believed Jackson was reaching for his gun. Jackson’s death inspired one of MLK’s most powerful speeches, reimagined for the film, which sparked the first Freedom March from Selma to Montgomery.

Bloody Sunday

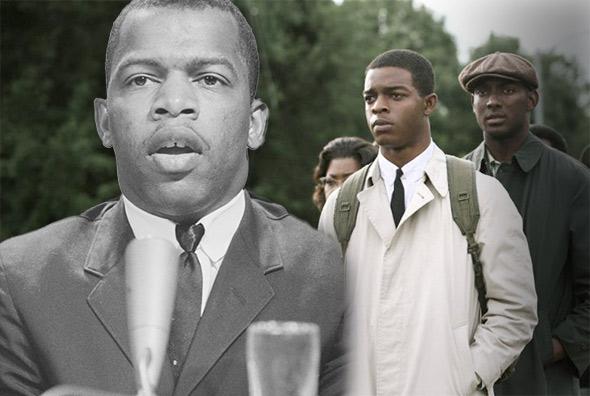

Photo illustration by Slate. Photo by Marion S. Trikosko/Stock Montage/Getty Images; Photo by Atsushi Nishijima/Paramount Pictures

On March 7, 1965, John Lewis and Hosea Williams attempted to lead more than 500 protestors on a 54-mile march from Selma to Alabama’s capital, Montgomery. There’s an ominous line early in that scene, as they march across the Edmund Pettus Bridge, where Williams asks Lewis if he knows how to swim—suggesting that might be the only way they survive this. Lewis says there weren’t any pools open to blacks where he’s from.* That exchange, like so many other moments in the film’s recreation of Bloody Sunday, was one DuVernay says came straight from Lewis’ memoir.

Alabama state troopers on horseback attacked the marchers using nightsticks and tear gas, as in the film, and we see both Lewis and Amelia Boynton (as well as dozens others) brutally assaulted and knocked to the ground. A photograph taken of Boynton while she was seemingly unconscious is recreated in the film and was printed in newspapers worldwide. Meanwhile, millions of Americans watched what happened in Selma that day when footage was broadcast on CBS.

The Second and Third Marches

Bloody Sunday and MLK’s calls for all to join a second demonstration in Selma led to an even bigger march, which included clergymen and ordinary citizens of various races, two days later. But, as we see, King turned that march back to Selma once they approached the same site of Bloody Sunday, concerned they wouldn’t make it much further without a court order allowing them to march peacefully to Montgomery with police protection. But before Judge Frank Minis Johnson (played in the movie by Martin Sheen) ruled in favor of the march from Selma, Ku Klux Klan members attacked three of the white ministers who’d traveled to Selma to march with King that day. (The film only shows two.) One of them, James Reeb (played in the movie by Jeremy Strong), died that same night.

Days later, President Johnson introduced the Voting Rights Act of 1965 to Congress, which he later signed into law on Aug. 6, 1965. On March 17, King and 8,000 others completed the march from Selma to Montgomery. DuVernay says she relied on the cover of the September 1968 issue of Ebony to recreate the outfits King and his wife, Coretta Scott King (Carmen Ejogo), wore that day.

MLK and Coretta Scott King’s Relationship

Photo illustration by Slate. Photo by Morton Broffman/Getty Images; Photo by Atsushi Nishijima/Paramount Pictures

In the film, the relationship between King and his wife is a strained one. In a particularly tense scene, she asks him to confess to cheating after receiving audio of a man, presumably King, having sex with another woman. At the time, Hoover had spearheaded an FBI investigation into MLK’s activism in an attempt to link him to the Communist party, tracking his every move and wiretapping his phone lines. (We see the call logs from those taped conversations pop up on screen throughout the film.) And though those tapes have since been sealed by a court order until 2027, at least two that suggest MLK engaged in extramarital affairs have come to light, and we now know that the FBI threatened to leak them to the public.

That’s not the only point of contention between the couple in the film: While King is in jail following the demonstration at the county courthouse, Coretta meets in secret with Malcolm X (Nigel Thatch) on his visit to Selma. She tells King it was to temper the feuding between the two civil rights leaders, though King doesn’t at first react kindly to her speaking with someone whom he doesn’t trust, especially behind his back. In a 1988 interview, Coretta described the conversation between herself and Malcolm X as taking place much like how it’s shown in the movie, saying it gave her hope that MLK and Malcolm X would soon reconcile their differences. Malcolm X died just days later.

*Correction, March 6, 2015: This article originally misspelled the name of the Edmund Pettus Bridge.