This article originally appeared in Vulture.

Walk into the Strand Book Store, at East 12th and Broadway, and the retail experience you’ll have is unexpectedly contemporary. The walls are white, the lighting bright; crisp red signage is visible at every turn. The main floor is bustling, and the store now employs merchandising experts to refine its traffic flow and make sure that prime display space goes to stuff that’s selling. Whereas you can leave a Barnes & Noble feeling numbed, particularly if a clerk directs you to Gardening when you ask for Leaves of Grass, the Strand is simply a warmer place for readers.

In the middle of the room, though, is a big concrete column holding up the building, and it looks … wrong. It’s painted gray, and not a soft designer gray but some dead color like you’d see on a basement floor. Crudely stenciled signs reading BOOKS SHIPPED ANYWHERE are tacked to it. Bookcases surround the column, and they’re beat to hell, their finish nearly black with age.

This tableau was left intact when the store was renovated in 2003. Until then, the Strand had been a beloved, indispensable, and physically grim place. Like a lot of businesses that had hung on through the FORD TO CITY: DROP DEAD years, it looked broken-down and patched-up. The bathroom was even dirtier than the one in the Astor Place subway. You got the feeling that a lot of books had been on the shelves for years. The ceiling was dark with the exhalations from a million Chesterfields. There were mice. People arriving with review copies to sell received an escort to the basement after a guard’s bellow: “Books to go down!” It was an experience that, once you adjusted to its sourness, you might appreciate and even enjoy. Maybe.

That New York is mostly gone, replaced by a cleaner and more efficient city—not to mention a cleaner and more efficient Strand. “Books to go down!” is extinct. So is Book Row, the Fourth Avenue strip that fortified the readers and writers of Greenwich Village. Though there are signs of life in the independent-bookseller business—consider the success of McNally-Jackson—few secondhand-book stores are left in Manhattan. Only two survive in midtown, and the necrology is long. Skyline on West 18th Street, New York Bound Bookshop in Rockefeller Center, the Gotham Book Mart on West 47th—closed. Academy Books is now Academy Records & CDs.

So, then: Why is there still a Strand Book Store?

***

In large part because of Fred Bass. He’s pretty much the human analogue for the store’s gray column. His father, Ben, founded the Strand around the corner in 1927, and he was born in 1928. Ask him about his childhood, and he recalls going on buying trips on the subway with his father, hauling back bundles of books tied with rope that cut into his hands. (“Along the line, we got some handles.”) Ask him about the 1970s, and he’ll tell you about hiding cash in the store because it was too dangerous to go to the bank after dark. He’s 86, and he still makes buying trips, though mostly not by subway. “Part of my job is going out to look at estates—it’s a treasure hunt.” New York, to him, “is an incredible source—a highly educated group of people in a concentrated area, with universities and Wall Street wealth. The libraries are here.” Printed and bound ore, ready to be mined.

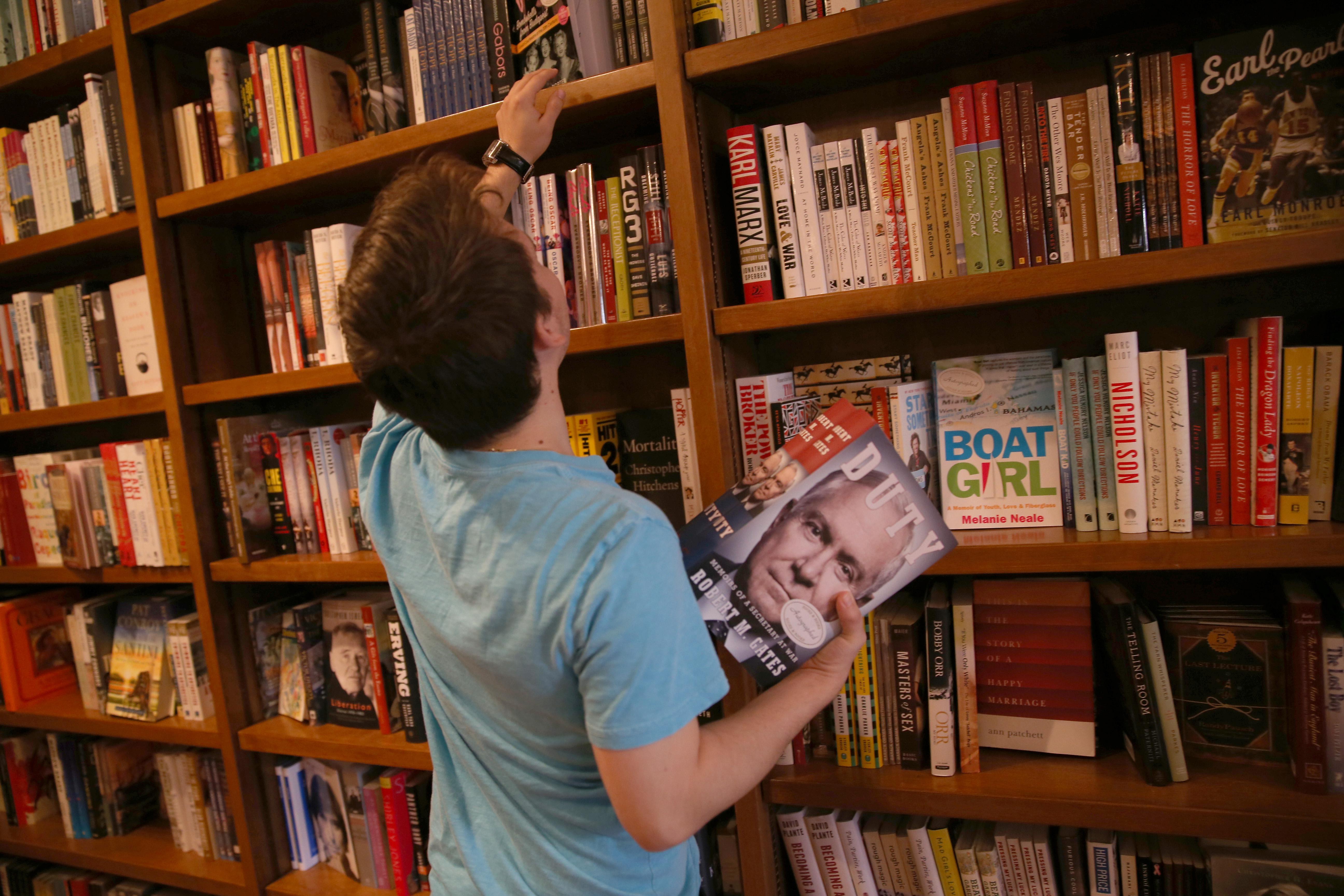

Four days a week, he’s on the main floor, working the book-buying desk in back. Stand there, and you’ll see the full gamut of New York readers. Critics and junior editors, selling recent releases. Academics. Weirdos. “Book scouts,” who pan for first-edition gold at yard sales and on Goodwill shelves. They walk in with heavy shopping bags and leave with a few $20s. Usually fewer than they’d hoped: The Strand rejects a lot, because unsalable books are deadweight. Whatever arrives has to go out quickly. “Our stock isn’t stale,” Bass says. “You come in, and there’ll be new stuff continually.” Slow sellers are culled, then marked down, then moved to the bargain racks outside, then finally sold in bulk for stage sets and the like.

Secondhand books have to be judged individually as they come in, a process that requires time and experience. (A couple of buyers have been on the job upwards of 40 years.) Though it takes less experience than it once did: Arriving books now have their UPCs scanned, and the database “gives us information where it used to be guesswork,” says Bass. “The guesswork was so great then, I filled up an 11,000-square-foot warehouse with unsold books.” He pauses, deadpan. “Using my expertise.”

All of this suggests that the Strand is a used-book store. It isn’t, not exactly. Over the past decade or so, new books have come to represent about 40 percent of sales. They constitute, Bass explains, a more predictable business: “New books, we can sell 50, 100, 200 copies of. I make less money, but it’s a little bit more scientific. The used-book business, we have a bigger market—of course, we have to carry a bigger inventory.”

Those new books are also profitable because of a source almost unique to the Strand: broke editorial assistants. When the Strand buys their review copies, it pays about a quarter of the cover price, sometimes less. They’re indistinguishable from new, and the Strand sells most of them as such. (When Bass buys from wholesalers, he generally pays about 40 percent of list.) Publishers hate this gray market but accept it; one book publicist I know cringes when she sees her press releases peeking out of copies at the store. Bass shrugs: “I tell them it’s the cost of doing business.”

If the old used-book Strand is built around Fred Bass, the new Strand is a joint production with his daughter, Nancy Bass Wyden. She started working here three decades ago as a teenager, and the family has done well since: Fred lives in Trump World Tower, and Nancy married a senator, Ron Wyden of Oregon. (She is charming with me, although a few bloggers say that she’s not so patient with her employees.) You get the sense that she’s trying to leave the core of the business intact while branching out beyond East 12th Street.

For example, at Fifth Avenue near 21st Street, there’s a satellite Strand built into a Club Monaco. It’s spotless, selling mostly new books plus some expensive first editions. “Not a home run,” Fred says, “but it’s working.” Adds Nancy, “We now have this expanded customer base—people who are Club Monaco shoppers who may not have been to the Strand before.”

The Basses have also tapped into New York’s great subsidizing resource: the global rich. If you’ve bought $15 million worth of living space on Park Avenue, it probably has a library, so what’s another $80,000 to fill those shelves? Make a call to the Strand with a few suggestions—“sports, business, art”—and a truckful of well-chosen, excellent-condition books will arrive. (Fred recalls that when Ron Perelman bought his estate on the East End from the late artist Alfonso Ossorio, the Strand had just cleared out Ossorio’s library; Perelman ordered a new selection of books, refilling the shelves.) In more than a few cases, the buyers request not subject matter but color. In the Hamptons, a wall of white books is a popular order, cheerfully fulfilled.

Nancy has also grasped that the Strand’s future can be bolstered by selling things besides books. Fifteen percent of the store’s revenue now comes from merch: T-shirts, postcards, notebooks, superhero action figures (they’re near the graphic novels), and especially those canvas tote bags, produced in dozens of variations. The success of the tchotchke business is, she says, one way in which book shopping has changed. Whereas individuals used to come in and root around for hours, today’s buyers shop faster and in a targeted way, often in groups. More tourists come than ever, and books about New York are piled up by the front for them. The store also has a big event space, and the wine flows regularly: launch parties, signings, a book-swapping mixer created in partnership with OkCupid. Bookstore visits are “a social thing,” Nancy explains as we walk past a wall of T-shirts. She points to one that displays a John Waters quote: “If you go home with somebody, and they don’t have books, don’t f**k em.” She chuckles: “My father hates that one.”

***

Are there existential threats to the Strand? There are. E-books, which require no retail space, have cut into best-seller sales. The Strand has pushed back with remaindered hardcovers, placed by the front door under a sign reading LOWER-PRICED THAN E-BOOKS.

There’s also the Strand’s relationship with its unionized employees, who were organized by the UAW back in the ’70s. They just signed a new contract this past month. Mostly, the labor-management situation seems equable; still, every few years, when contract time comes, someone writes a news story about strife. “The union demands something up here,” says Fred, gesturing, “and we’re down here … There’s always going to be conflict.” In general, the union is quite aware that the Strand is not Google, and the Basses are perfectly aware that relative harmony benefits the business. In October, a pro-union staffer named Greg Farrell published a graphic-novel-style book critical of both management and the union’s representatives. Oddly, he still works at the store. More oddly, the Strand sells the book.

Internet used-book sales, too, would seem to be a long-term concern. When you visit Amazon or AbeBooks (which is owned by Amazon) and search for an out-of-print title, your results are usually listed from cheapest to most expensive. The first “store” on the list often turns out to be a barn full of books in rural Minnesota or Vermont. Some are charity stores, selling donated books—no acquisition costs at all. They certainly aren’t paying Manhattan overhead. Yet here, too, the Strand is holding on, owing mostly to that churning turnover and the quality of its stock. That barn isn’t going to have many of last year’s $75 art books for $40, and the Strand always does. Plus there are the only–in–New York surprises that come through the store’s front door. Opening a box can reveal a Warhol monograph that will sell for more than $1,000, or an editor’s library full of warm inscriptions from authors.

If that’s the future, could the Strand wind up virtual? Surely operating out of one of those barns would be cheaper. “Not with our formula,” says Bass firmly. “We need the store. This business requires a lot of cash flow to operate,” and much of it comes in with the tourists. That funds the book-buying, which supplies the next cycle of inventory.

Which requires this expensive retail space, and the renovation of 2003 did not just come from a desire to spiff up. It happened because of a specific event, one that probably saved the Strand: In 1996, after four decades of renting, the Basses bought the building. “Frankly,” Fred says, “for a while, I thought, This isn’t going to work anymore.” He’d always negotiated the lease renewal with his landlord at the nearby Knickerbocker Bar & Grill—they once had to reconstruct their deal the next day, after knocking back one too many—and a bookstore would not have been able to hang on to 44,000 square feet for much longer. It took Bass two years to hammer out a price, but once he became his own tenant, he paid rent at a significant discount. “When I want to negotiate my own lease,” he jokes, “I have to go to the bar myself.” He’s got leverage in those talks, because the store occupies four floors out of 12, and rent from the others flows back into the business. Warehoused books, once upstairs, are now in much cheaper space across the East River.

There is only one true long-term threat to the Strand, and it comes from within. Bass, whose entire life has revolved around this business, loves bookselling. It appears that Nancy does, too. The store makes money, if not a crazy amount, and the family has good reasons to keep it going. But the Strand is, when you get down to it, a real-estate business, fronted by a bookstore subsidized by its own below-market lease and the office tenants upstairs. The ground floor of 828 Broadway is worth more as a Trader Joe’s than it is selling Tom Wolfe. When a business continues to exist mostly because its owners like it, the next generation has to like it just as much. Otherwise they’ll cash out. If Nancy stays, the Strand stays. If her kids do, too, it stays longer. Simple as that.