An earlier version of this article was published in 2012. This version has been expanded to add discussion of Interstellar.

Christopher Nolan likes to turn your world upside-down. In each of his films, there comes a moment when you start to realize that the hero isn’t quite who you thought he was. When The Dark Knight’s Harvey Dent says, “You either die a hero, or you live long enough to see yourself become the villain,” he could be speaking about the fate of just about every Nolan protagonist: Leonard Shelby in Memento, the dueling magicians in The Prestige, even Cobb from Inception.

This theme is reinforced by Nolan’s repeated use of a very unusual shot: The roll, a camera movement in which the camera does a barrel roll that turns everything in view on its side, or—if it keeps turning—upside-down. Directors and cinematographers use this very rarely, but Nolan loves it, and he employs it at key moments for a particular purpose: To make us feel, as the protagonist does, that the world is literally and figuratively turning on its head.

In The Dark Knight, Nolan uses the shot at the moment when the Joker comes closes to convincing Batman of his worldview. Like all the main Dark Knight trilogy villains, the Joker is more interested in changing Gotham’s perception of itself than in taking physical control of the city, and so when Batman has finally captured the Joker—leaving the villain hanging upside-down—the Joker switches from fighting Batman with bazookas to trying to defeat him with a rather lengthy barrage of ideas. In short, he wants Batman to embrace moral anarchy, break his “one rule,” and kill him. Just as Batman seems to consider this, the camera rolls on its side, and soon the Joker appears to be right-side up, while the world behind him has turned upside-down. (I’ve embedded a montage of this shot and most of the others mentioned in this post below.) As the Joker puts it, at the scene’s close: “Madness, as you know, is like gravity: All it takes is a little push.”

In Inception, still Nolan’s most mind-bending film, he turns the world on its side again and again. Sometimes this is literal. The most striking instance is when Ariadne (Ellen Page) literally folds Paris in on itself until Parisians are strolling down the inverted streets above her. But the camera rolls come later. First, there’s the action set piece that takes place in a barrel-rolling hotel hallway—Nolan constructed a massive rolling set to pull it off—and throughout the scene the camera rolls on its side with the action.

But it’s at the end of Inception that we once again lose our equilibrium just as we’re seeing the protagonist from a new angle. It happens when we finally witness how the hero, Cobb, ended up (arguably) killing his wife, Mal. Cobb explains how he succeeded in convincing her that she was dreaming, and therefore needed her to kill herself to escape the dream. Just as we’re beginning to wonder if we can trust Cobb anymore, the camera, once again, is rolled on its side. Cobb and Mal are both lying on their sides on the fatal train tracks, but they now appear to be right-side up.

Screengrabs from Inception © 2010 Warner Bros. Entertainment, Inc.

Even when he doesn’t employ the shot, Nolan—in conjunction with his brother and frequent screenwriting partner Jonathan Nolan—delights in upending the viewers’ sense of the world. The Inception scene on the train tracks recalls a similar scene from Nolan’s breakout film, Memento. That film returns again and again to the moment when Leonard and his wife have been knocked to the bathroom floor by intruders who have broken into their house. Lying on their sides and slipping out of consciousness, they stare across the floor at each other as the life drains from Leonard’s wife’s eyes. When we return to the same shot later, we discover that Leonard’s wife actually survived, that Leonard eventually killed her, and that Leonard has been lying to himself, and giving himself puzzles to solve, to keep himself from confronting the truth.

This is the worldview of Nolan’s movies: The world is a horrible place, and many of us are horrible people, but we trick ourselves into feeling otherwise. No one thinks of themselves as a villain, and even the murderers tell themselves stories about how they’re actually the heroes. As Teddy (Joe Pantoliano) tells Leonard in Memento: “So you lie to yourself to be happy—there’s nothing wrong with that, we all do it. Who cares if there’s a few little details you’d rather not remember.”

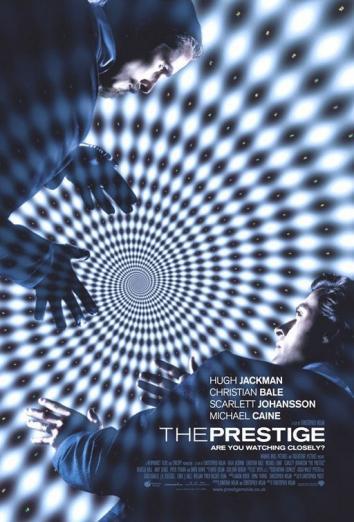

Official poster for The Prestige

There are two similar lies—“a few little details” that the heroes would rather forget about—at the heart of The Prestige, in which the obsessions of two men drive them to commit horrible acts. Alfred Borden (Christian Bale) kills his opponent’s lover and then lies to himself about whether he really did it. (She drowns while unable to escape from a particularly tough knot that he tied, but he says he can’t remember which knot he used. The trick she was trying to perform, incidentally, is called “the Upside Down.”) His opponent Robert Angier (Hugh Jackman), meanwhile, ends up committing routine murder in order to perform a particularly spectacular magic trick, but he convinces himself it’s worthwhile and tries to forget the cost.

Why does Angier do it? His answer gives us a clue as to why Christopher Nolan so enjoys turning his worlds upside-down:

You never understood why we did this. The audience knows the truth: The world is simple. It’s miserable, solid all the way through. But if you could fool them, even for a second, then you can make them wonder, and then you … then you got to see something really special … You really don’t know? It was the look on their faces.

When I first wrote on this subject in 2012, I couldn’t be completely sure Nolan’s use of this shot was deliberate, but with Interstellar I’ve become convinced. The use of the roll comes early on, and it follows the pattern we’ve come to expect from the director almost exactly. (Spoilers follow for Interstellar.) The shot occurs when Professor Brand (Michael Caine) is showing Cooper (Matthew McConaughey) the space shuttle Cooper will use to seek out a new habitable planet. The space shuttle is more or less what one would expect, but the massive hangar is more than meets the eye. Brand says he’s hoping they’ll be able to save the inhabitants of the dying Earth (he calls this “Plan A”), instead of just leaving them behind and starting a new civilization from scratch (he calls this “Plan B”), and Cooper only understands his plan when he bends his head to the side: As the camera’s gaze rolls with him, we see that if you look at the hangar on its side, you can see that it’s a space station made to launch into orbit.

Official posters forInception and Interstellar

The use of the roll made me think that Brand was probably lying, and sure enough he later admits as much on his deathbed. There never was a Plan A. There was no hope for saving the Earth. It was just a lie meant to convince Cooper that he could be the hero to save his family. (Cooper himself gets by on a similar lie: He promises his daughter he’ll come back, when really he doesn’t know that.) When Cooper learns this, and realizes that he could never return, he doesn’t think he’s a hero at all. He wishes he stayed.

It’s what happens next that makes Interstellar unique among Nolan’s movies. For the first time, Nolan’s universe has a God, or something like one—in this case it’s the transcendent, benevolent “they”—and through their power, and his love for his daughter, Cooper is able to make good on his promise. He sends the data his daughter (now an adult played by Jessica Chastain) needs to make Brand’s lie into a reality.

Perhaps Nolan has found faith, or at least hope. Or perhaps he’s now simply less interested in bringing his audience harsh realities. His wife and co-producer Emma Thomas recently told the New York Times Magazine, “Where, in the past, he never made movies for any reason other than the fact that he wanted to see those movies himself, now he wants to make films he can watch with his kids.” Whatever the cause, while once his world was “simple … miserable, solid all the way through,” he’s now decided to make us wonder.

Video edited by Chris Wade.