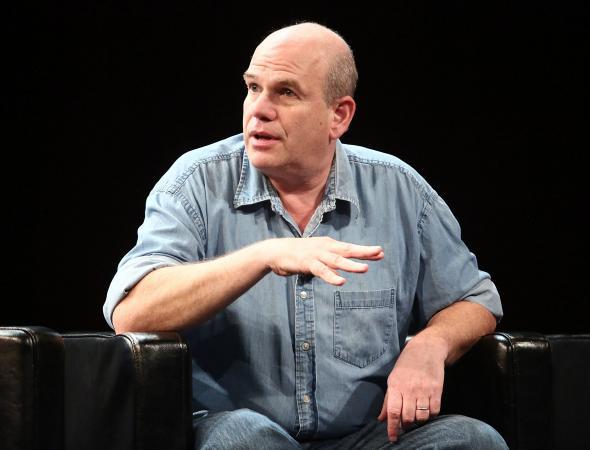

“The city to me is the only possible vehicle we have to measure human achievement,” David Simon said earlier this month, in a rapturously-received keynote speech for Observer Ideas, a one-day, TED-like collection of thought-provoking talks held at London’s Barbican Centre on Oct. 12. “We’re an urban species now,” Simon continued. “If you look at Karachi or Mexico City or Hong Kong or London or New York or Yonkers or Baltimore or any of these other places, the pastoral is now a part of human history. We’re either going to figure out how to live together in these increasingly crowded, increasingly multi-cultural population centers or we’re not. We’re either going to get great at this or we’re going to fail as a species.”

Simon explored Baltimore on The Wire and The Corner and New Orleans on Treme, which finished its four-season run late last year. Now he’s working on another city-centered project for HBO: Show Me a Hero. Based on a book by New York Times reporter Lisa Belkin, the six-part miniseries recounts how a court-ordered requirement to build a small number of low-income housing units in a white neighborhood of Yonkers created what Simon called “such racial strife and such an astonishing level of political rage and fury, it paralyzed the city for a couple of years, destroyed political careers, and alienated neighbor from neighbor.” Due to air next year, the series will star Catherine Keener, Alfred Molina, Winona Ryder, Simon regular Clarke Peters, and Oscar Isaac as the young mayor at the heart of the controversy. Paul Haggis will direct.

Simon sees his most acclaimed show, The Wire, as “an argument for the city,” he said in his London talk. “There was never a thought that everybody could walk away. Walk away to where? We’re in the city for keeps, and the argument The Wire was intending to make was we’re going to attack this and we’re either going to achieve this or we’re going to fail, and what’s at stake is nothing less than self-governance,” he said.

“It’s really kind of terrifying how controversial the notion of a shared future now is,” he continued. “We’re either going to figure it out together or there will be two Americas. There’ll be an America with its own private police force behind a gated community and there will be the Americans who didn’t catch the wave, and the future going’s to become a lot more brutish and a lot more cruel.”

After the talk concluded, I spoke with Simon in a nearby pub. We talked about Ferguson—which Simon wrote about extensively on his website—about the novelistic aspect of his TV shows, and about the relationship of those shows to the truth.

Note: This conversation has been condensed and edited.

When you wrote about Ferguson back in August, you prefaced your thoughts with older stories from the Baltimore Sun. When you saw what was happening in Missouri, did you have a sense of déjà vu?

I was astonished that the Ferguson police department was 95 percent white. That creates a culture that’s not particularly conducive to carefully attending to civil rights issues. The idea that the police can shoot unarmed people … the age of the personal video has created a new accountability in cases of police use of force, and that’s a good thing. In my city, the newspaper [the Baltimore Sun] has been more or less eviscerated but nonetheless came out with a great story about a week ago about the ubiquity of police violence and settlements against citizens who were beaten. It’s an astonishing number. When I was covering the police … you know, one every three months, one every four months. It’s like quadrupled since then.

Why is that?

I don’t know and I’m curious. Obviously it’s a lack of professionalism. The city’s no more dangerous than it was. I have a very unpopular theory, but it’s based on the reporting I did for The Corner. The most brutal police that I saw in West Baltimore when I was doing The Corner as a book were African-American, which is the opposite of Ferguson. I would be curious about the racial breakdown of all the cops who were implicated in all the settlement cases the Sun reported. Just from my own reporting, once you remove the racial stigma of beating the shit out of a guy, it almost becomes easier. A white cop has to think before he raises his nightstick or draws his gun, and now he especially has to think because the racial implications are always there, as they are in Ferguson … It’s disturbing to me and I don’t wish to tar all the African-American cops. I know a lot of good black police officers. A lot of what motivates the police towards contempt for the huddled masses is class, not race. I think class is always present regardless of the race of the cop.

With their three-dimensional characters, multi-leveled narratives, and underlying passion for social justice, your shows have been compared to realist novels in the tradition of Dickens, Zola, or Sinclair Lewis. Do you think they are engaging with viewers in a way that novels no longer do?

I’m working with Richard Price, whose Clockers was so valuable, really The Grapes of Wrath of the crack epidemic. And Dennis Lehane, whose The Given Day about the Boston police riots is magnificent. And George Pelecanos. There’s a lot of socially-aware writing going on. Maybe not the literary novels so much—I don’t know.

Listen, I have lousy numbers for TV, but on a bad night I’ll get two million viewers. If you sold two million hardback books, you’d have a New York Times bestseller for a year. But at the same time, nobody’s running to do The Wire. I’ve sort of shown Hollywood how to make a show that nobody wants to watch, so nobody’s trying to replicate it.

You’ve written nonfiction books, fictional dramas that refer to real events, and dramatizations of nonfiction stories. Which do you think does a better job of getting to the “truth” of a true story?

A lot of people would say this is what gets me in trouble—my shows are “too real” and a little more drama would stand me in good stead. Let me be very clear: When I’m doing a fictional piece like The Wire or Treme, it didn’t have to happen in the manner described, but it has to be in the context of what could have happened in that time and place—that’s what I’m interested in. And with the pieces that are nonfiction, I’m wedded to the events. And that is very valuable to me, but not necessarily to television. I’m often walking away from the best narrative choice because I know it didn’t happen.

Stories have a beginning, a middle, and an end, and until very recently American television didn’t plan the end. You just tried to keep the franchise going for as long as you could. That lent itself to mediocrity eventually, because you need to be thinking about your last page as soon as you start filming your first.

The second thing is, there has to be a reason why you’re telling the story, a purpose. It doesn’t have to be political. But you have to have a reason for the story to exist. The reason can’t be, “I got two really good actors so they’re going to have a great market share and NBC’s giving me 9 o’clock on Wednesday.” It’s got to be, if you’re going to spend your life writing stories, make the fucking stories matter to you. It’s just real simple. But incredibly that’s not part of the equation in the entertainment industry.

There’s no better story told about what’s both good and vile in America than Huck Finn. If one thing survived, and it was Huck and Jim on the raft, you’d know an awful lot about who we were as a people. Twain knew the story he wanted to tell, he knew why he was telling it, and then he fucking nailed it. There’s more truth in that book about America, about race, about the best part of the American spirit than in a million history books.