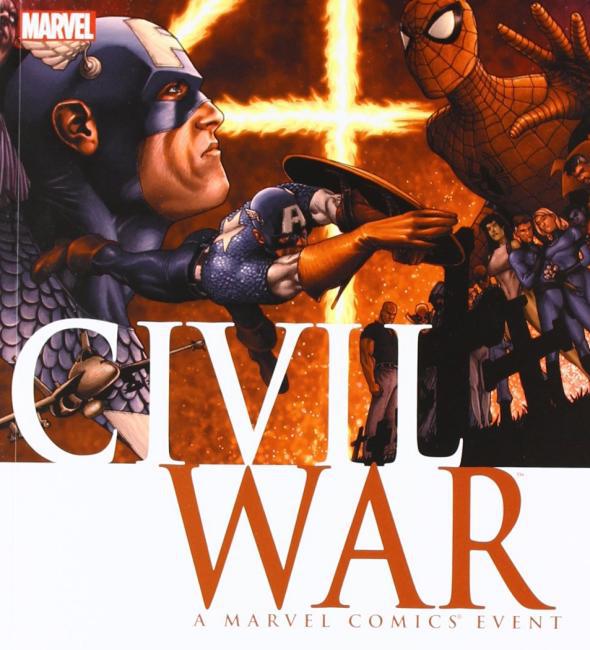

Next summer, Marvel Comics will reboot the 2006 Civil War storyline, in which a superhero registration law divides heroes into two camps: The pro-registration side, led by Iron Man, and the anti-registration side, led by Captain America. This coincides with news that Robert Downey Jr. will join Chris Evans in the upcoming Captain America 3 as a co-star, as part of a plan to bring Civil War to the Marvel Cinematic Universe.

For fans of comic books and superhero movies, this is a huge deal. Civil War transformed the status quo of Marvel Comics and set the stage for almost everything that followed in Marvel’s top-tier properties, including the creation of new Avengers teams (featuring Dr. Strange, Ms. Marvel, and Black Widow, all characters with rumored or forthcoming films), not to mention an alien invasion. Civil War will give Marvel a chance to reshape its film properties, deal with the departure of older stars, and continue the brand into the next decade.

Which is why it’s important the studio gets the story right, and doesn’t fall into the traps of the original Civil War. Because, for all of its importance to the brand, Civil War—or at least the main seven-issue limited series—is bad. Completely, unfathomably bad.

It begins with an incident in Stamford, Connecticut, when the New Warriors—a team of young superheroes—ambush a group of villains for their reality TV show. The fight spills into the street, and one of the villains—Nitro—uses his powers to destroy a city block, killing 600 civilians, including 60 children and many of the New Warriors. Public sentiment turns against superheroism, with attacks on known heroes—including the Fantastic Four’s Human Torch—and a push for superhero registration. As Daredevil says to a group of heroes debating the law, “[T]his has been building up for a long time. Stamford’s just the straw that broke the camel’s back.”

So far, so good. We see the consequences of unregulated superheroism, the core of the case for registration—the government should know who uses superpowers for crime-fighting—and the beginning of the opposition, best expressed by Falcon, an ally to Captain America. “The masks are a tradition. We can’t let them turn us into supercops.”

And then it all goes off the rails.

In the real world, we have gun control laws. Yes, we all have the right to own and use guns, but this often comes with public obligations, like licensing, background checks, or—in rare cases—actual registration for weapons.* For someone writing a story on superhero registration, guns are a useful template for how to treat superheroism.

And in a way, that’s what Marvel does. Except, rather than borrow from real world gun registration, it borrows from the loony anti-registration fears of gun fanatics, who imagine that registration and background checks are the beginning of a slippery slope to jackbooted thugs and a fascistic New World Order. Marvel could have given a sensible treatment of registration. Instead, it gave us a superhero version of NRA paranoid fantasies.

As such, superhero registration is less like gun registration and more like the draft, where heroes are forced to become federal employees, reveal their identities to the public, and act as law enforcement. This enrages a whole host of heroes, including Luke Cage (aka Power Man), who compares the registration law to slavery and Jim Crow in one of the most glib exchanges I’ve ever read in a comic book. (When Iron Man asserts, “This is about breaking the law,” Cage counters, “Slavery used to be a law.”)

When Captain America goes to Maria Hill, the director of SHIELD (the spy agency that monitors heroes), to protest the registration law, she attacks him and forces him underground. In short order, Captain America becomes a libertarian freedom fighter—a 180-degree turn from his traditional positioning as a New Deal Democrat—and Iron Man, who supports registration, becomes a tyrant.

Pro-registration forces—which soon include Spider-Man and Mr. Fantastic—begin rounding up resistors, and in one fight, they kill a member of the “Secret Avengers,” Captain America’s anti-registration superhero team. Eventually, Iron Man and Mr. Fantastic build a prison in the Negative Zone (a parallel dimension where time stands still), where unregistered heroes are held in a Guantanamo-esque indefinite detention. Eventually, the fight spills out into New York City, where pro- and anti-registration forces battle until Captain America—on the verge of killing Iron Man—surrenders.

Tony Stark is appointed director of SHIELD, anti-registration heroes go underground or escape to Canada, and the Marvel Universe barrels toward a police state, as villains like Norman Osborn (Green Goblin) take advantage of the new status quo to infiltrate government and consolidate power. Eventually, the U.S. government employs a team of “Dark Avengers”—villains turned employees—and launches a siege on Asgard, home of Thor.

The whole thing is a mess, and its messiness stems from the decision to slant the entire debate in favor of anti-registration by reducing it to only two choices: Freedom or tyranny. The fact that superheroes killed hundreds of people in Stamford at the beginning of the series is dropped as soon as it becomes narratively inconvenient for the anti-registration side.

Of course, it’s always been a bit hard to use superheroes to engage with serious real-world debate. But it’s possible, and regardless of where you stand on the question of gun registration laws (you can probably guess my sympathies), it’s not difficult to see that this story was handled poorly.

Hopefully, in rebooting Civil War and bringing it to the silver screen, Marvel will approach the story’s political resonance more thoughtfully. There’s some reason to hope that they will: The Marvel Cinematic Universe has already shown some surprising depth in its depiction of an unchecked intelligence agency and a U.S. government that executes enemies without trial (see: Captain America: The Winter Soldier), and the rumor is that the fallout from Avengers 2: Age of Ultron will prompt Tony Stark to reconsider the role of superheroes as forces who have no accountability to the people (which unaccountability he celebrates in Iron Man 2).

For those of us who think too much about comic books and superheroes, a well-told Civil War story would be something to look forward to. There are legitimate problems with superheroism (and the kind of exceptionalism it implies), and we’re far enough into the age of superhero films to start to deal with them.

*Correction, Oct. 20, 2014: This post originally misstated that registration of individual guns was broadly required in the United States. Only a handful of states require weapon registration.