When I think of Punky Brewster, I think of a fearless fashion icon, a magnet for mischief, and a model of plucky individualism for girls of the ’80s and ’90s. And I know I’m not alone in this. A tribute by HelloGiggles to the actress who played Punky oozes with admiration, and more than a hint of envy: “We all wanted to be her, but Soleil Moon Frye actually was her.” Moon Frye herself reflects, “She was old school before old school was old school! She was hip-hop! She’s all about expressing individuality.” She’s inspired a modest catalog of fanfiction and a seemingly infinite scroll of Pinterest results.

It’s been 30 years since Punky Brewster premiered—the show debuted on Sept. 18, 1984, just a couple of days before The Cosby Show brought us one of TV’s great feminists—and I decided to mark the occasion by revisiting the character that inspired well-behaved younger me to dream a little more boldly. Brewster, I thought, embodied punk values, albeit ones that were packaged for a family-friendly audience. She fought the establishment (specifically, the Department of Child and Family Services) and embodied non-conformity (mismatched shoes!). Her signature phrase, “Punky Power,” invokes “girl power,” a term that, a few years after her arrival, became popular among feminist punks before going mainstream. Punky Brewster was a feminist icon. Right?

Well, not exactly. Punky did embody aspects of both punk and feminist thinking, it turns out. But she was trapped inside a show that was all about reinforcing mainstream middle class values circa 1984. This was, after all, the mid-1980s, the throes of the family values era, when Reagan Republican Alex P. Keaton somehow spawned from hippie parents. For the uninitiated, the premise of Punky Brewster is that after 8-year-old Penelope “Punky” Brewster is abandoned by her mother at a shopping center, she takes up residence in an empty Chicago apartment. She and her impossibly obedient golden retriever, Brandon, are soon discovered by building manager Henry Warnimont (George Gaynes), who eventually becomes her foster parent. In the first five minutes alone, we’re introduced to a sassy black woman (Susie Garrett as neighbor Mrs. Johnson) who seems unlikely to transcend the stereotype she plays, and we witness multiple instances of fat-shaming (“You could spray-paint a novel on your underwear!” Henry says to Mrs. Johnson). The first few episodes’ portrayal of the foster care system comes across like a cheery, wildly unrealistic antidote to the poor orphan story in Oliver Twist.

But no one remembers this show for its screenwriting, or as a pioneer in on-screen representations of race and gender. Punky Brewster the show was a vehicle for Punky Brewster the character. Most episodes, though, feature two Punkys: the one who defies the rules, and the one who ultimately gets put in her place. And this second Punky nullifies everything the first one stands for.

The first Punky regularly expresses anti-authoritarian values. Many of the episodes begin with her committing some sort of transgression: She uses Henry’s camcorder without permission, breaks it, and lies about how the lens got cracked. She cheats on a test and lies about it until she gets caught. She runs away when she feels like a burden to Henry and his new girlfriend. But these scenarios invariably end with an admission of guilt, an apology, and promise to behave better in the future.

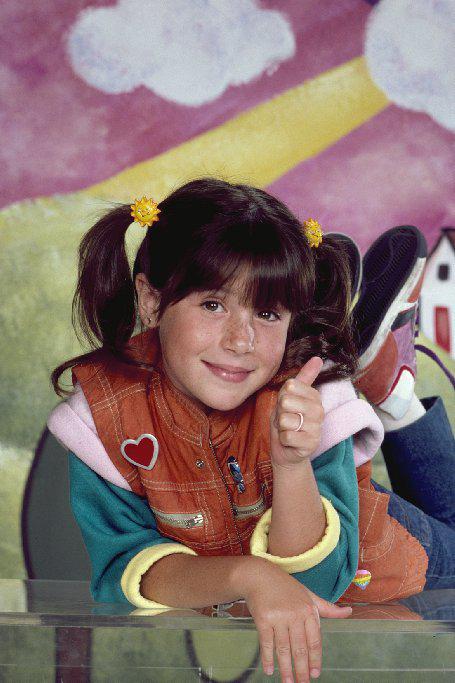

NBC Universal

In one of Punky’s more feminist-leaning episodes, “My Aged Valentine,” she disavows the notion of having valentines at all. More specifically, she rejects her schoolmate Conrad, who’s expressed an interest in being hers. When he kisses her on the cheek despite her protestations, she gives him a nice shiner in return. Even after being forced to apologize, she continues to assert that she doesn’t need a man in her life. “I can jump higher than most boys in my class,” she says. “I can hit harder, and I can spit farther. What do I need a boy for?” The episode ends with Henry explaining that she might not want one now, but she should keep her heart open to the possibility of love in the future. “I have a hunch you may think differently someday,” he tells her. “If you keep your heart open, you make room for someone to come into it.” Thus, Punky’s girl power is presented as temporary, part of a childish tomboy phase.

Punky ends up being not so different, really, from another popular TV character who arrived a few years after her: Michelle Tanner, the youngest child on Full House, famously played by Mary-Kate and Ashley Olsen and best known for her catchphrases (“You got it, dude!”). Michelle, too, is motherless, attracted to trouble, and always set straight at the end of the episode. The only thing she’s missing is the nonconformist wardrobe.

Punky Brewster could have been a breath of fresh air in a conservative TV era, but mismatched shoes do not a riot grrl make. She was a pioneer trapped in a fictional world that wouldn’t let her flourish. So we can appreciate her for the spirited and creatively styled little girl she was. But mostly we should be thankful that she helped pave the way for the Buffys and the Blossoms that followed.