No sooner had the most recent Doctor Who episode, “Listen,” finished broadcasting Saturday on BBC1 in the U.K. and BBC America here than many prominent critics, geek sites, and high-profile fans were stepping forward to call it the best episode in years. The members-only forums at Gallifrey Base are notoriously hard to please, but 77 percent of users rated “Listen” 8 or higher (out of 10) in the weekly poll. Even avowed haters of Doctor Who showrunner Steven Moffat, who wrote the episode, were proclaiming it a masterpiece.

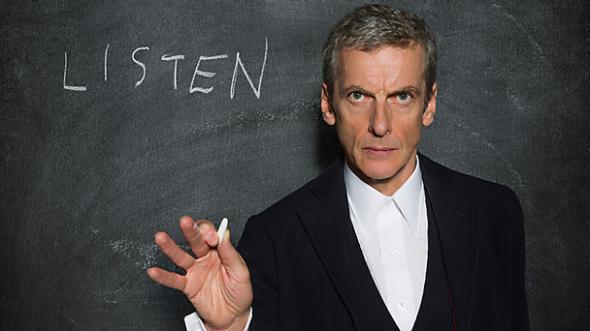

What makes this broad acclaim particularly remarkable is that “Listen” is a surprising departure from typical Doctor Who. Peter Capaldi’s 12th incarnation of the Doctor has gotten a little stir-crazy traveling companion-less in time and space for a while, and in his increasingly unhinged solitude he’s cooked up a theory: “Suppose that there are creatures that live to hide? That only show themselves to the very young, or the very old, or the mad, or anyone who wouldn’t be believed?”

He picks up on-again-off-again companion Clara Oswald (the increasingly marvelous Jenna Coleman), who’s still smarting from a disastrous date with damaged-veteran-turned-teacher Danny Pink (Samuel Anderson), to test a notion: that the commonly-experienced nightmare about a hand coming out from under your bed and grabbing your ankle is no nightmare at all, but an encounter with one of these perfectly-hidden creatures. The Doctor and Clara’s pursuit of this stealth-monster—which may or may not even exist—takes them backwards and forwards in time, powerfully impacting Danny’s life and culminating in a shocking encounter with the very origins of Doctor Who.

“Listen” is easily the Moffat-iest episode of Doctor Who ever, a bluntly literal depiction of his frequently expressed thesis that “Doctor Who doesn’t take place in outer space or the future, it takes place under your bed.” To achieve this level of peak-Moffat, he’s reused any number of signature tropes:

* a monster that functions according to the rules of human perception and the logic of childhood fears (“Blink,” “The Impossible Astronaut”)

* the Doctor allying with a frightened child (“The Eleventh Hour”)

* the Doctor influencing a person’s development at various stages of their life (“The Girl In The Fireplace,” “A Christmas Carol”)

* a bedside speaker giving crucial advice to a sleeping child (“The Big Bang”)

* predestination paradoxes based on time travel (any number of Moffat’s episodes)

That’s been the primary knock on the episode from those who didn’t like it: that, as Strange Horizons reviews editor Abigail Nussbaum tweeted, “If you set out to write a parody of the Steven Moffat event episode, you couldn’t do much better than this.”

But accusing an artist of “repeating himself” isn’t actually a complete argument. Artists repeat themselves all the time. Internet fan-forum scrutiny of Shakespeare’s plays would not have been kind. (“Going back to the girl-dresses-as-a-boy well again?”) The key is in how they repeat themselves. Writers don’t utterly reinvent themselves for each new work. Their toolboxes evolve incrementally over time. At their best, tropes aren’t content, they’re tools, techniques for digging into different ideas.

With “Listen,” Moffat deployed his bag of tricks to devise one of the most innovative Doctor Who stories ever, one that breaks new ground both structurally and thematically. Unlike virtually every other story in the series’ history, in this one there may be no real problem to solve, no alien menace, no despotic dystopia. Every situation we see—including the stunning bedspread and farmhouse sequences, both instant classics—is brought about by the Doctor reacting to no clear problem at all. Indeed, every peril-trope depicted in “Listen” may have only come about through the Doctor’s needless instigation.

Which leads into the greatest element of “Listen,” what truly sets it apart as a landmark story: Moffat uses these tropes to powerfully reconsider Doctor Who’s contract with children. Indeed, it’s hard to properly understand “Listen” without thinking about it in the context of Doctor Who as a children’s program. As recurring cast member Alex Kingston has pointed out, the biggest difference between U.K. and U.S. fandom is that a significant portion of the former is made up of children, many of whom are frightened—and then emboldened—by watching Doctor Who. The monsters appear, and they’re scary, but then the Doctor appears, tells a joke, and outwits them.

Many children’s earliest experiences of fear are irrational ones—monsters in the dark, in the closet, outside the window, under the bed. And because these monsters can’t be seen or defeated, and because your parents don’t believe you, these fears can instill a potent sense of powerlessness. So often children define the kind of adults they want to become in reaction to this powerlessness. This is what Moffat is digging into here: Because we see Danny at different points in his life, we see how he defines his adulthood in response to his childhood fear. He becomes a soldier, the strongest thing he can think of to be … except that now he’s broken and closed-off as a result. With the climactic revelation that the Doctor too was a frightened child once upon a time, we can see this same process at work in our hero as well. He’s reacted by becoming DOCTOR WHO, the larger-than-life hero who strides the cosmos laughing at fear. But this strategy has its limits too, as we see in the paranoia that’s overtaken him at the beginning of the episode.

It is finally in Clara that Moffat proposes the ideal response to fear. Perhaps because she wasn’t afflicted as a child in the same way as the Doctor and Danny, Clara is willing to live with fear as an ongoing, low-level, simmering reality in her life. She accepts that it’s OK to be afraid, no matter how old or strong you get. And she goes that one crucial step further than the Doctor or Danny, beyond the idea that fear can make you powerful, to the natural conclusion that fear can make you empathetic: “If you’re very wise and very strong, then fear doesn’t have to make you cruel or cowardly,” she says, near the end of an episode which proves that, deployed cleverly enough, Doctor Who can do anything. “Fear can make you kind.”

Previously

A Beginner’s Guide to Doctor Who

These Are the Classic Doctor Who Episodes You Need to Watch